Dr. Adam Sachs is no stranger to discipline — whether practicing Wing Chun Kung Fu or performing neurosurgery.

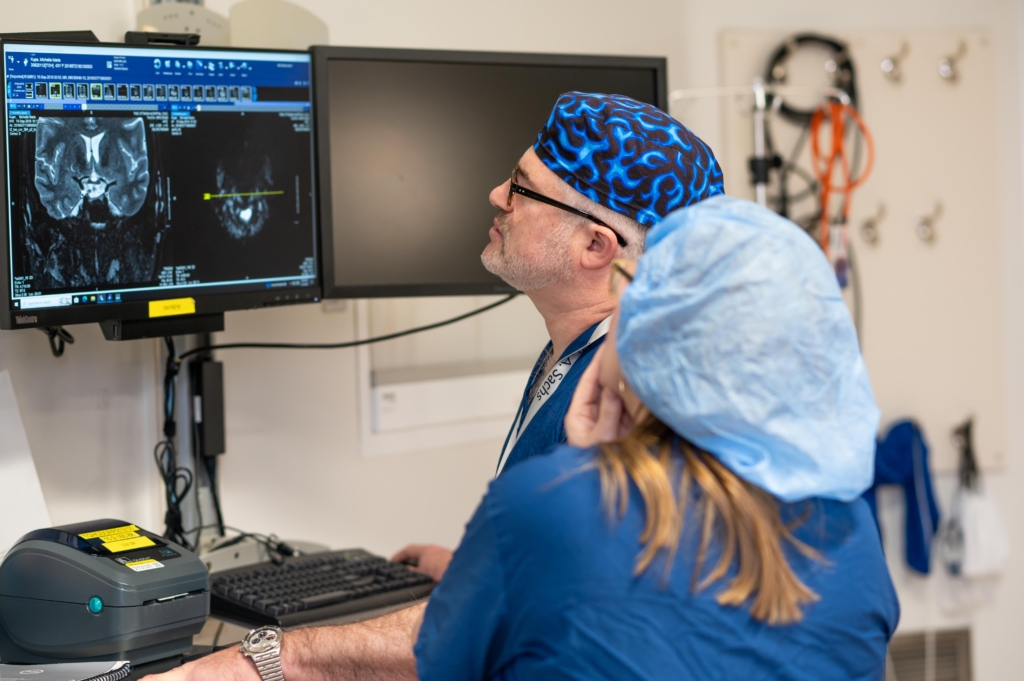

As Director of Neuromodulation and Functional Neurosurgery and Scientist at The Ottawa Hospital, Dr. Sachs is changing the way we think about the brain through his research into brain-computer interfaces.

After studying math and physiology at McGill University for his undergraduate degree, Dr. Sachs saw the potential to bring them together through neuroscience and pursued a medical degree at McMaster University before landing a neurosurgery residency back at home in Ottawa.

Find out how Dr. Sachs thinks brains are like computers, what he loves about The Ottawa Hospital, and why you might find him fighting a co-worker on his break.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your early years?

A: I was born and raised in Ottawa with three brothers, and we were all into skiing. We started quite young. As a teenager, I got into martial arts, Wing Chun Kung Fu specifically, and I’ve continued that my entire life.

In school, I was OK, but it took me until university to really get serious about my studies.

Q: How did you decide to pursue medicine, specifically neuroscience?

A: My dad was a surgeon at The Ottawa Hospital, so I had medicine on my mind at a young age. But in high school, I thought I’d go into math or physics and be a teacher. Then, I realized I could use math as a doctor and try to model medical processes as mathematical problems. I thought the best organ to apply that to would be the brain because the brain is a biological computer and can be hacked into.

I did my master’s in neuroscience and math, modelling a certain aspect of human vision and comparing it to how computer programmers handle computer vision. I described how I could apply this to medicine in my application to medical school, and they obviously bought it!

Q: What exactly does your role as a neurosurgeon at The Ottawa Hospital entail?

A: I practice a type of neurosurgery called functional neurosurgery.

Other forms of surgery might look at structural issues. I’m also a spine surgeon, and if somebody has a broken back, that’s a structural problem. If somebody has a tumour in their brain, that’s a structural problem we can address by removing as much of the tumour as possible. An aneurysm is a structural abnormality in a vessel.

But chronic pain might not have a structural cause. At least, not one we’re able to detect. Parkinson’s is another functional problem. With functional neurosurgery, we deal with issues using electrical manipulation or stimulation.

Q: You divide your time between caring for patients and research, can you describe the research you’re currently working on?

A: We’re currently recruiting for a clinical trial testing a brain-computer interface for people who are living with severe physical disability. We’ll put an implant in their brain, plug it into an HDMI cable, and write algorithms to try and decode their thoughts. Not private, deep thoughts like, memories, but basic thoughts, like wanting to move in a certain direction. We’ll offer something like a coffee, a cell phone, and a cookie, and look to answer basic questions like, “Which does the person want?”

These “cognitive” implants will help us enhance the performance of a robotic arm being controlled by a “motor” implant. We’ve been publishing for decades looking at cognitive signals from the prefrontal cortex using these types of devices, and in this trial, there will be a small number of people we’ll interact with fairly intensively.

Q: When Michelle Kupé came to The Ottawa Hospital for an extremely painful nerve condition, how did you and your team help her?

A: Michelle came to us with trigeminal neuralgia, a condition where it feels like you’re being shocked or stabbed in the face. The pain is severe and can be triggered by simply moving your face, brushing your teeth, taking a shower, or even just being exposed to wind. It’s a well-known condition in medicine, but the severity of Michelle’s case stood out.

Michelle had an artery pressing on her trigeminal nerve, and it had worn down the insulation around the nerve. In the majority of cases, this happens because of the way people are wired — where their nerves happen to fall.

Medication is the first line of treatment, and for many people, it’s sufficient. But surgery was necessary for Michelle, and is for many others. We found that in addition to the artery, there was also a large complex of veins around the nerve, which made it technically demanding. We surgically detached the artery and veins from the nerve, called microvascular decompression, and put a tiny, cigar-shaped piece of Teflon between the artery and the vein to protect the nerve.

She’s had a very durable result, and today, she’s living without nerve pain.

Q: What is the most exciting research happening in your field?

A: AI and deep-learning models are advancing almost every aspect of basic neuroscience. Talking about AI is like talking about statistics — it’s now ubiquitous. It can be used for patient data or to look at biological signals recorded from the body. I record signals from the brain, and we’ve started using deep learning algorithms and more advanced AI algorithms to help us make sense of those signals.

Q: The Ottawa Hospital is currently working towards the creation of a new, state-of-the-art health and research centre to replace our aging Civic Campus. What will this new hospital mean for your patients?

A: Neurosurgery is a highly technical field on the vanguard of new technologies. We use navigation, intraoperative imaging, biplanar fluoroscopy, robot assistance, intraoperative monitoring of neurophysiological function, tumour fluorescence seen on specialized microscopes, and other technologies that require certain infrastructure. They’re setting up the underlying architecture for all of this at the new campus, which will allow us to offer the latest in neurosurgery to our patients.

Q: Why do you choose to work at The Ottawa Hospital?

A: The reason I am excited to work here is because the values of the hospital align with my own: compassionate treatment and working together. I am also able to find the support to do the things I want to do clinically and in the lab. What I’ve found is that everyone working here wants to solve problems together.

Q: How does Kung Fu continue to play a role in your life?

A: I see a big connection between martial arts and neurosurgery. In fact, in my mind, there’s a continuum between Wing Chun and neurosurgery — they’re not completely distinguishable. They both involve body control and awareness, discipline, and they are both rooted in scientific principles and human physiology.

In Wing Chun, we consider ourselves brothers, and I actually have a Kung Fu brother, Doug, who’s a phlebotomist at the hospital. When we wanted to train, we’d reserve a conference room and use a break to practice together. Sometimes people walked in and his fist would be about to connect with my face. It can be a little difficult to explain!