There were moments Dr. Alan Chalil didn’t know if he would become a neurosurgeon, but those were few and far between. Usually, it seemed like he was born to be one, and in many ways, he was. The neurosurgeon, researcher, and Director of The Ottawa Hospital’s Surgical Epilepsy Program knew what he wanted to be from an early age, and he pursued that goal with dedication from day one.

Today, Dr. Chalil is transforming the way we understand and treat epilepsy, in Ottawa and far beyond, through his practice-changing research and incredible clinical work.

Find out who Dr. Chalil’s first patients were, what key lesson he learned in his undergrad, and why he’s excited about the future of epilepsy research and care.

Q: What were your early years like?

A: I grew up in Syria and I was a nerdy kid. I mostly focused on studying, playing chess, painting, and playing guitar. I was never that excited to wake up and go to school, but in Syria, they ranked your grades and published them for everybody to see. There was some shaming there. I was always proud of being top of my class and never wanted my name to be two or three, so that was my motivation to go to school.

Q: What was your favourite subject in school?

A: Physics! I was always a fan of physics and anything mechanical. I loved cars, watches, planes. Even the mechanism on a lighter would fascinate me. I would build little cars with electric engines, and it taught me how to use my hands. I always knew I wanted to do something with my hands.

Q: What did you want to be when you grew up?

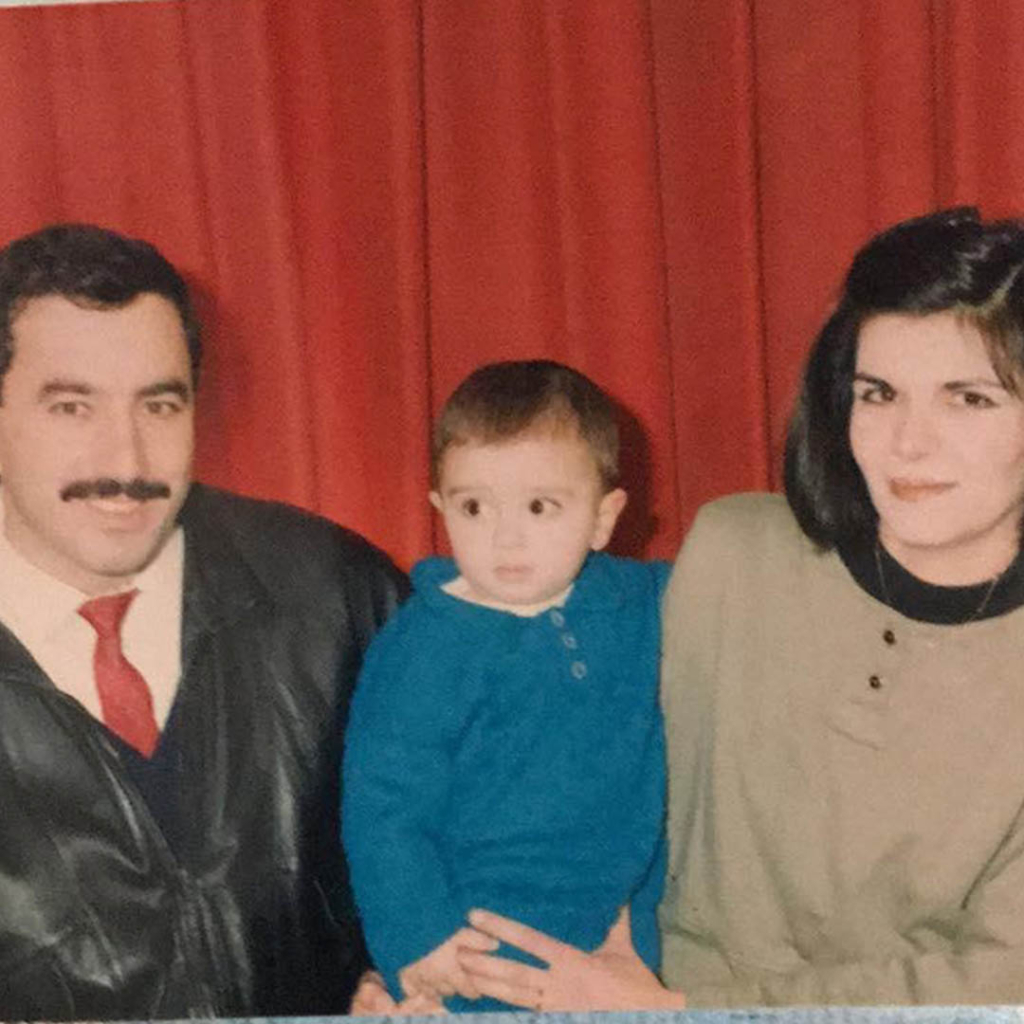

A: I wanted to be a neurosurgeon. My dad was a neurosurgeon, and he always said it wasn’t a good idea and that I should do something different. But ever since I was a kid, I thought he had the coolest job. I used to do operations on my teddy bear’s head.

There were certain times I didn’t think it was achievable, though. I moved to Canada on my own in 2006, between Grade 11 and Grade 12. That’s when I realized how difficult it was to get into medical school.

That was probably one of the hardest years of my life. Jumping into a new society when you’re a teenager is a big transition. I’d never used English conversationally, so I got a job in a grocery store to learn and worked in grocery stores and in construction up until grad school.

Q: What did your path to medical school look like?

A: I applied to the University of Waterloo for mechanical engineering and health sciences, and while I initially accepted for engineering, I changed my mind because everyone told me I couldn’t get the grades for medical school in that program. I still regret that.

I failed at getting into med school multiple times, but during my undergrad, I worked in a lab for physiology and lipid fat metabolism, and I wound up doing a master’s in that lab. When I was finishing that, I decided to apply for medical school at the University of Toronto one last time.

The funny thing is, after I applied, they sent me an offer for an interview. I was so excited that I ran out of the lab mid-experiment to tell my supervisor, and he hugged me. But then I got an email 10 minutes later saying the offer was an error. Two days later, I got yet another email, but I didn’t believe it, so I deleted the email. They had to email me again with “FOR REAL” in the subject line.

After medical school, I did my residency back in London and then a fellowship at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Q: What’s the most important lesson you learned in school?

A: There was one course in my undergrad that was really interesting: statistics. I was great at it, and I did all the extra assignments. I was that kid in the class — the annoying one, the teacher’s pet. When it was time for the exam, I went into it with 110% because of all the extra credit I’d done. I stayed up all night studying, then decided to get a little shut-eye at 6:00 a.m. When I woke up, it was 9:30 a.m. The exam was at 8:30 a.m. It was such a nightmare that I honestly didn’t know whether I was still asleep. I’d missed three-quarters of the exam, and I wound up with an 89% in the class.

It was the definition of the phrase “the opposite of good is perfect.” I learned a lot more than statistics that day.

Q: What drew you to epilepsy?

A: When I started medical school, epilepsy wasn’t even on my radar yet. During medical school, you can apply for multiple specialties, but I didn’t think I’d be as good a doctor anywhere else, so I only applied for neurosurgery. I matched in London, which is a very old program and has the biggest epilepsy program and the biggest functional neurosurgery program in Canada.

There, I met Dr. Andrew Parrent, who had one of the most profound impacts on my life. I was fascinated by his understanding of neurology and anatomy. In his clinic, I saw people like me — living normal lives, not looking sick — but who had epilepsy.

For many neuro cases, you’re trying to make the best of a bad situation — removing a tumour, resolving an injury. But with epilepsy, people typically have an intact brain, and you’re trying to find the balance of preserving neurological function while giving them freedom from seizures. It raises the stakes.

Q: What’s something people might find surprising about epilepsy?

A: What’s interesting is that most people think of epileptic seizures as like what they see on TV, as general convulsions. But epileptic seizures can manifest in a lot of different and weird ways. It can feel like a déjà vu sensation, like a face or arm twitch, or like an absence, where you stare into space. Alice in Wonderland type seizures make you feel like you’re small, but like the room is huge.

Epilepsy is not as simple as generalized convulsions. Most people don’t even know they’ve had seizures.

Q: What would you tell someone who has just been diagnosed with epilepsy?

A: I would tell them that no matter what, they’re still the same person they were before. I’d tell them, depending on their epilepsy, there’s a very good chance they’ll respond to medication — up to 70%. I would be supportive and sympathetic. It’s a very serious disease, and it’s important we catch it early.

Q: What is one of the groundbreaking procedures you’re currently using for epilepsy?

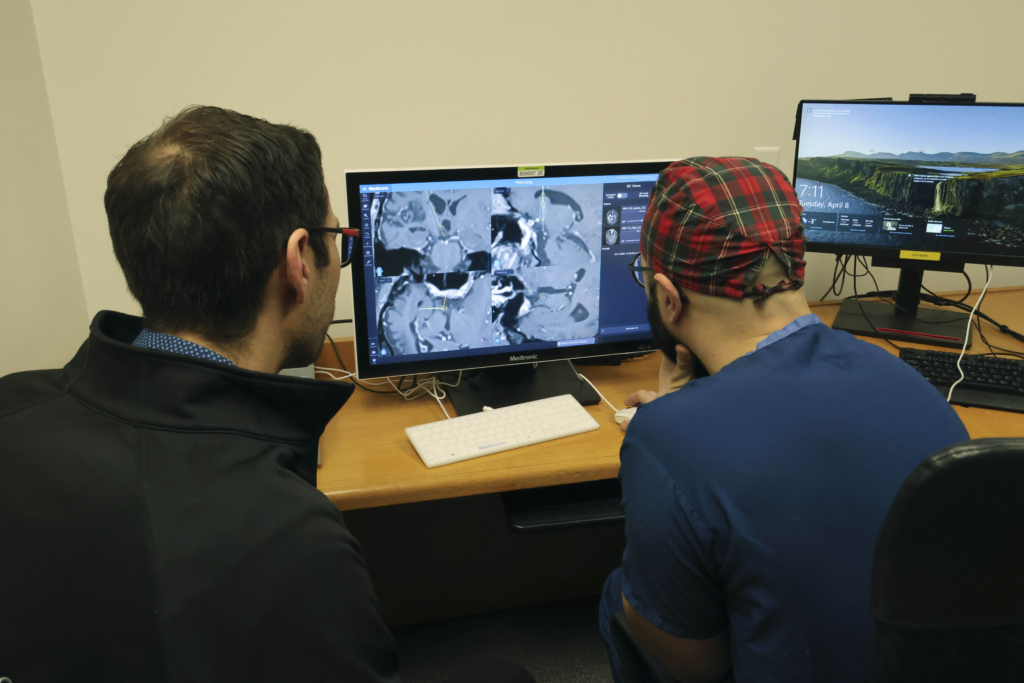

A: Something I specialize in is stereoelectroencephalography (stereo EEG), a minimally invasive procedure to pinpoint the source of seizures. Epilepsy is a network disease, and with this procedure, we try and identify which network in the brain is abnormal, then we implant tiny electrodes in the brain, down to a millimetre accuracy, to study where the seizures are coming from and how they’re spreading to other networks.

I have to answer two questions: where are the seizures coming from, and does the patient need that area or not? Every part of the brain is important, but there are some parts that could be causing you seizures, and there may not be a huge or negative impact if we disconnect that part of the brain. Stereo EEG helps us find out how to disconnect these areas with minimal impacts elsewhere.

Q: What is the future of epilepsy treatment?

A: The future of epilepsy is very tied to its past. In the last few years, we started experimenting with older treatments that we used decades ago, like radiofrequency ablation. But we’re using them differently today — we’re smarter, more targeted, and more methodical.

Neurosurgery is so young that I can trace my lineage back to the father of neurosurgery a century ago, Dr. Harvey Cushing. He trained Dr. Wilder Penfield, a famous Montreal neurosurgeon, who trained someone else who trained someone else and so on until the neurosurgeon who trained me.

We still don’t know a lot. And you don’t know what you don’t know; that’s the fascinating part. We’re operating at the edge of our knowledge. We’ve made a huge amount of progress in the last 50 years. The pioneers of the past, like Dr. Penfield, paved the way for epilepsy surgeons today. I’m sure Dr. Penfield was also operating at the edge of his knowledge. We’re trying to do the same, but we have the advantage of retrospect.

I think in the future, there’s going to be a big role for brain-computer interfaces and brain implants. We are already implanting devices that communicate with the brain: they sense a seizure and try to stop it by producing small electric currents in the brain.

The future is bright for epilepsy because as long as there’s interest and funding to do that, we’ll continue pushing forward on a daily basis.

Q: What does community support mean for your patients?

A: Community support is huge because we’re trying to deliver minimally invasive options to patients to cure their epilepsy or reduce their symptoms. A lot of the equipment we’re using is cutting-edge and expensive. When we do a stereo EEG, it can cost $10,000 to $15,000. Right now, we’re collecting funds for a robot that can help us insert the electrodes for stereo EEG faster and more accurately.

Q: Why did you choose to work at The Ottawa Hospital?

A: The chance to start an epilepsy program drew me to Ottawa. There are multiple centres in the country, and two others in Ontario, but this was a chance to build a program from scratch and bring everything I learned in London and Atlanta to create something unique and different. I don’t have any doubts that we will become one of the busiest, if not the busiest, epilepsy programs in the country. To be a part of that story would be a huge honour.

Q: What motivates you to come into work every day?

A: What I truly look forward to is changing someone’s life for the better, even if it’s just a small improvement in pain or a reduction in their seizures. When you operate on an epilepsy patient who’s having seizures every day for years, and they wake up without them, it’s very satisfying. I tend to be very self-critical, too, and think I need to do better. I just want to improve on what I did the day before, and that’s a huge motivation. At a certain level, I am still competing to be at the top of that list from elementary school.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not at work?

A: I go to the gym every morning first thing. Other than that, you’ll find me with my daughter trying to teach her chess. She can name all the pieces and knows where all the pawns go. She’s just 18 months, though, so she needs closed captions; she’ll say something to me, and I’ll look at my wife Courtney to translate.