Published: March 2023

The search for the silver bullet for sepsis has been decades in the making. However, The Ottawa Hospital is taking a big step forward in the next phase of a world-first clinical trial using stem cells in patients with septic shock — not so much a silver bullet, but a seed that could lead to future innovative treatment options and impact millions of patients. The hope is to not only save more lives but also improve the quality of life of those who do survive this devastating illness.

Sepsis is caused by our own body’s response to infection. When that infection spreads through the blood stream and over-activates the immune and coagulation systems, it can cause the heart and other organs to fail. Sepsis is associated with a death rate from 20% to 40% and upwards from that, depending on the patient. Survivors of this devastating condition often have their quality of life impacted and often for the long term. Sepsis knows no borders and impacts people globally.

What is Sepsis?

Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre is an intensive care unit (ICU) physician and senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital, and it’s her care of critically ill patients that has motivated her research into sepsis. Over the years, she’s witnessed the debilitating impact it can have on patients and their families. “It’s why I’m doing this research. As researchers, we love science. We love posing questions and the thinking that goes with these questions, and we love the answering those scientific questions. But the main reason we’re doing research is to help patients,” says Dr. McIntyre. “If there’s some way we can just move that needle to help these patients and their families, that just means so much.”

The global impact of sepsis

Sepsis is recognized as a global health priority. It’s estimated there are 48.9 million cases of sepsis annually and 11 million sepsis-related deaths — those account for almost 20% of global deaths. It is also the leading cause of death among COVID-19 patients.

To put that in perspective, a study published in 2021 led by researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and ICES (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) showed that severe sepsis is linked with higher mortality, increased hospital readmission, and higher healthcare costs. In Ontario alone, sepsis related costs are estimated at $1 billion per year.

“It’s the complexity of the infection and the challenge that drew me to the research, but also knowing the potential to really help patients and see if we can make them better.”

– Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre

According to Dr. McIntyre, sepsis is the most common reason why patients are admitted to ICUs. “They account for about 20% of the cases in the ICU at our hospital. From a provincial glance, over a four-year period, there were 270,000 cases of patients that were admitted to hospitals in Ontario for infection — about 30% had the more severe form of sepsis, with infection plus organ failure which amounts to about 67,500 patients a year in Ontario alone – it’s staggering,” explains Dr. McIntyre.

These data are a key motivator to learn more about sepsis and how to treat it. “It’s the complexity of the infection and the challenge that drew me to the research, but also knowing the potential to help patients and see if we can make them better,” says Dr. McIntyre.

Putting a face to the impact of the infection

Ten years ago, sepsis changed the life of Christine Caron — a single, working mother with four children who, at the time, ranged in age from 15 to 24. Throughout the winter and spring of 2013, she hadn’t been feeling well. Then in late May, while playing tug-of-war with her four dogs, her left hand was accidentally nipped. “It wasn’t a serious bite, just a break in the skin. I had no redness or pain, so I washed it out and disinfected the area,” recalls Christine.

Four days later when Christine was at work, she realized she hadn’t gone to the bathroom all day — eventually she learned this was because her kidneys were shutting down. The following day, she set out for a morning run. “I was winded and had to walk home but felt better after a shower. Later that day, I had terrible stomach pain — like someone had punched me in the stomach — and felt disoriented. I went home and slept. My son woke me up at one point to say I was breathing funny, but I assured him I was fine and fell back to sleep. I was shocked when I woke up and realized how long I had been asleep,” says Christine.

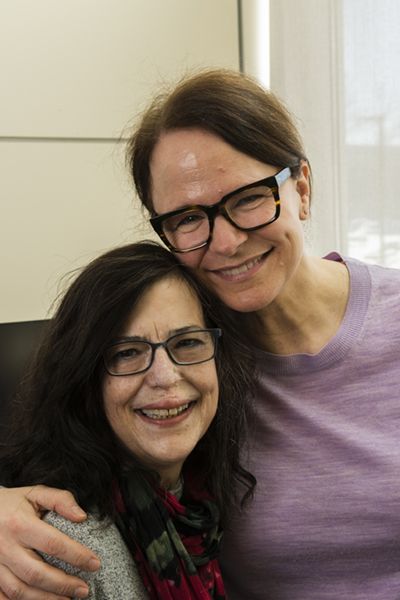

Christine Caron is a survivor of sepsis.

She remembers feeling agitated and more symptoms developed, including sweating despite feeling cold and becoming very thirsty. She went to a local urgent care centre, but it was closed. “I had no idea how sick I was, and the thought of sitting in an emergency department was overwhelming. I decided if I wasn’t feeling better in the morning that I would go to the hospital then.”

Later that night, while her children slept, she became very sick — flu-like symptoms as she describes it. “I lay on the bathroom floor, probably ‘till three in the morning. I thought about calling an ambulance, but I didn’t want to wake up my family,” says Christine. “I wasn’t thinking clearly. I now know this was delirium.”

The next morning, a friend took Christine to a local hospital. “I was dizzy, I could barely breathe. I handed my health card to the attending nurse and then I collapsed,” explains Christine.

Christine wouldn’t regain consciousness for a month. On June 13, she woke up at the Civic Campus of The Ottawa Hospital to learn the devastating news of what sepsis had done to her body. This was when she heard about septic shock for the first time. “I had bronchitis that progressed to walking pneumonia. It was this condition that compromised my immune system resulting in the reaction to the bacteria when I was nipped by my dog. It quickly escalated to septic shock.”

As it would turn out, the sepsis infection had caused irreparable damage. By June 22, Christine began a series of surgeries to amputate her legs, her left arm, and remove dead tissue from her remaining limb and her face — changing her life forever. Little did she know at the time, but this set her on a path of becoming a voice for sepsis survivors. By early July, she was released from the hospital and would learn a new way of life at our Rehabilitation Centre, where she learned to walk again and received support for PTSD. Today, Christine is an active advocate for sepsis survivors, awareness, and for research.

Moving the needle for sepsis treatment

For decades, there has been little progress in advancing specific treatment for sepsis, but world-first research at our hospital shows that a specific type of stem cells may be the key to helping balance out the body’s immune system to improve its response to sepsis. Laboratory studies and early clinical trial results were so promising that Dr. McIntyre’s research was awarded $2.3 million from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Stem Cell Network to begin a larger trial. “Researchers around the world have spent decades trying to find new therapies for septic shock, but so far nothing has improved survival, nor the quality of life for survivors of this devastating illness,” says Dr. McIntyre. “We urgently need new treatments for septic shock and to test them in randomized controlled trials like this one.”

This injection of funds will allow the team to expand the trial to 10 centres across Canada to see whether the stem cells can reduce patients’ needs for organ support in the ICU.

For Dr. McIntyre, this research, which is a huge collaboration among hospital colleagues, including Drs. Duncan Stewart, Dean Fergusson, and Shirley Mei, as well as colleagues throughout Canada and abroad. It provides hope that years of dedication to this mysterious illness may finally move the needle forward for sepsis treatment. “These stem cells hold, in my opinion, immense therapeutic promise for the treatment of sepsis, because these cells act through many mechanisms that relate to sepsis. Not only do they recognize and ultimately kill the bugs causing the infection, but they also calm the immune and blood-clotting responses that our body has to the infection,” explains Dr. McIntyre.

“I see this trial as the very first beginning — it’s a little bud, and we’re just going to grow from it.”

– Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre

And while Dr. McIntyre says her research has shown these cells have other benefits, such as restoring energy to the tissues, and reducing vessel leakiness and the swelling that goes with it, treating sepsis is still an enormously complex problem. “We can’t expect that there’s a silver bullet that’s going to completely cure sepsis, but from what we have learned so far, these cells have the potential to make a real dent in the immense death from sepsis, and we hope will improve the quality of life for survivors of this devastating illness.”

The “little bud” that will grow into future sepsis research

This clinical trial is just the starting point to learn more about this deadly infection, and the results will help inform future trials. As the research advances, and more is learned about how the body responds to these cells during sepsis, it will help identify future patients that may have the most to benefit. “So, I see this trial as the very beginning — it’s a little bud and we’re just going to grow from it,” explains Dr. McIntyre.

The growth of this research has been cultivated by what Dr. McIntyre describes as a major collaborative team approach. It includes researchers, both basic and clinical, cell manufacturing experts, trainees, project managers, clinicians, and nurses, as well as patient and family partners, and sepsis survivors, like Christine, who is the lead patient partner. “Working with these patient partners has just been illuminating about post-sepsis survivorship. People like Christine have been so helpful in enabling us to understand the need to study more about the survivorship of these patients and their families, and the quality of that survival,” explains Dr. McIntyre.

“Sepsis took so much from me — it scarred me in so many ways. We need to advocate and educate because sepsis does not discriminate.”

– Christine Caron

There’s a mutual admiration between the two women, who have each seen sepsis through a very different lens. Christine is thrilled to have her voice heard and to see that needle move forward. “Dr. McIntyre’s research is phenomenal because a lot of patients come out with organ damage, and stem cell research could save so much for so many people. Wouldn’t it be so wonderful if it did?” Christine adds, “Sepsis took so much from me — it scarred me in so many ways. We need to advocate and educate because sepsis does not discriminate.”

“If there's something that we can do to reduce death and help how patients survive this immense illness, we’ve just got to go there.”

– Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre

And so, for Dr. McIntyre, it’s those faces she sees in the ICU and those like Christine, who work alongside her, that continue to motivate her with each step forward in the search for answers in this challenging puzzle of sepsis. “If there’s something that we can do to reduce death and help how patients survive this immense illness, we’ve just got to go there.”

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.