A strange thing happened before John Chafe started working in Kenora in 1993. His eyes crossed. He didn’t know it at the time, but it was the first sign of a debilitating disease that would change the course of his life forever.

His family doctor told him he had the flu and prescribed antibiotics. But after a week, when his eyes remained crossed, he bought an eye patch and drove five hours from Thunder Bay to fill the temporary posting at a bank in Kenora. A week later, his eyes straightened and returned to normal. But then other symptoms started appearing, he was losing his balance and couldn’t walk in a straight line.

“I then started have difficulties walking straight. I completely failed a simple balance beam experiment at the Ontario Science Centre,” said John. “I mentioned these symptoms to a friend, who mentioned them to a friend, who fortunately happened to be Dr. Heather MacLean, a neurologist at The Ottawa Hospital.”

To Dr. MacLean, John’s symptoms sounded like multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system attacks its own central nervous system, brain, and spinal cord. John needed an MRI and spinal tap to properly diagnose his symptoms. The results were analyzed by Dr. Mark Freedman, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Research Unit, Neurology, who confirmed his diagnosis. John had an aggressive form of multiple sclerosis.

A different life after MS diagnosis

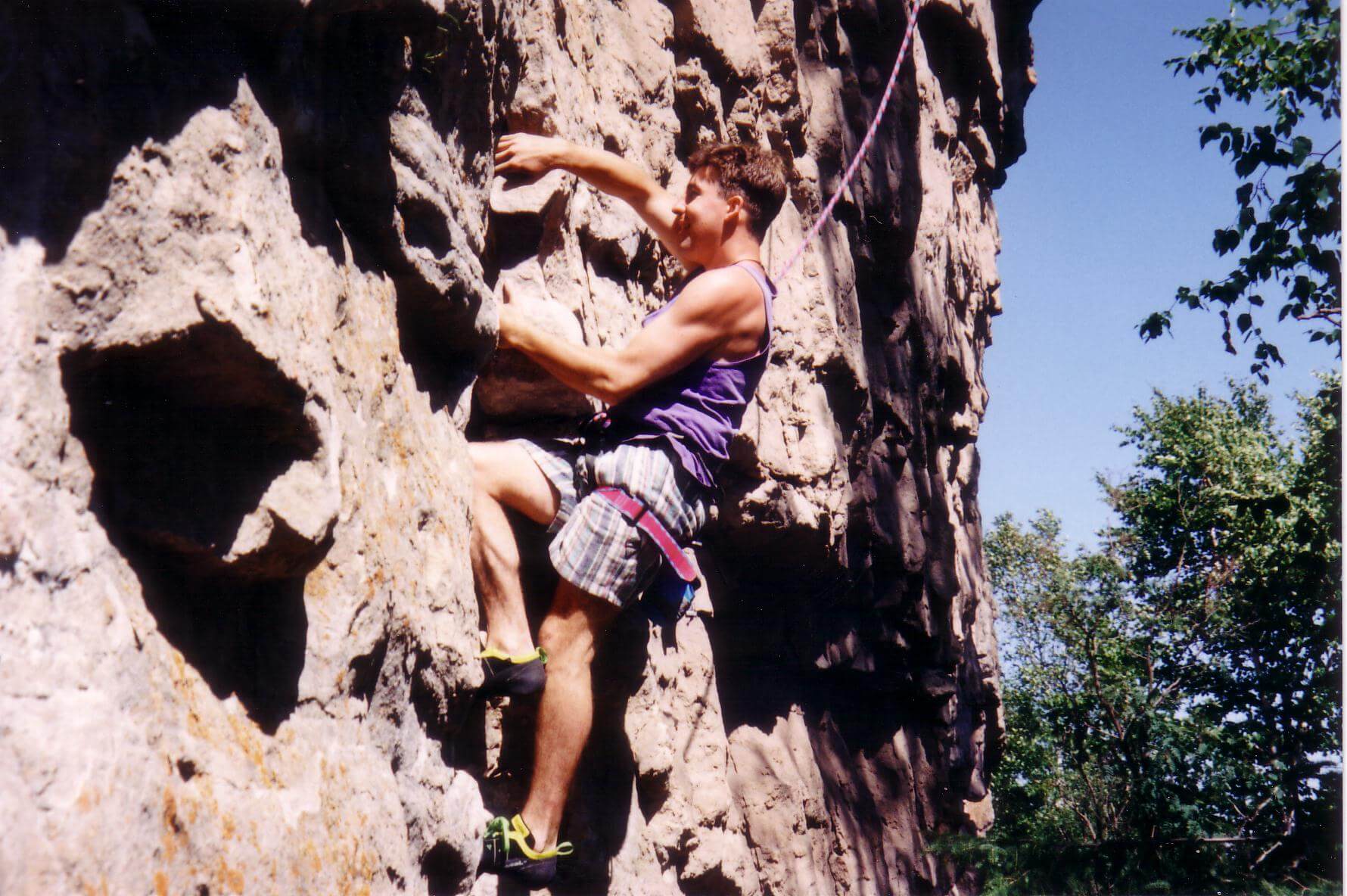

Incredibly interested in rock climbing and skiing, John didn’t give up his active lifestyle after his diagnosis, despite the fact that he was experiencing MS exacerbations – an attack that causes new MS symptoms, or worsens old symptoms – every eight months. He returned to Thunder Bay and opened a rock-climbing gym, thinking, “MS is not going to affect me.”

But it did. It completely sidetracked his life.

After suffering another MS exacerbation, John realized it was becoming more difficult for him to get out to see clients for financial planning sessions.

“I was stumbling along and thought, ‘How can I ask them to trust me with their money?’ My MS was getting worse and worse,” said John. “I needed a desk job, so I went into computer programming.”

His treatments weren’t helping. He needed a miracle. So he moved to Ottawa to be close to The Ottawa Hospital where we could receive the very best treatment.

Leading-edge clinical trial in Ottawa

One day, John heard Dr. Freedman on the radio talking about an innovative stem cell transplant study that he described as akin to pressing reboot on the immune system. Dr. Freedman was working with hematologist and scientist Dr. Harold Atkins, a professor of medicine at University of Ottawa, to see if a groundbreaking treatment would halt an aggressive form of MS.

When John met with Dr. Freedman, he told him he was interested in participating in this new study. Dr. Freedman agreed he might be a good candidate because he was young, generally healthy, and his symptoms were quickly getting worse.

“If you saw his trajectory, how fast he was becoming disabled going into the transplant. He should’ve been completely wheelchair bound, or worse, within two to three years,” said Dr Freedman.

John was willing to try an experimental treatment that had the potential to change that trajectory. “MS robbed me of my ability to climb, ski, and walk. I said, ‘I’m going to take a chance.’”

“John was very enthusiastic. That was a very important facet of his recovery,” said Dr. Freedman. “John has never been a quitter. He’s a stubborn guy. His goal was someday to end up on the ski hill again.”

Preparing for treatment

For almost a year, John underwent the exhaustive testing by Dr. Atkins and Marjorie Bowman, the bone marrow transplant nurse, to see if he was physically and mentally suitable for the clinical trial. They wanted to ensure he was prepared to go through the intensive trial treatment and accept the risks, which included death.

“This is fundamentally different than every other treatment,” said Dr. Atkins. “What we’re doing is getting rid of the old immune system and creating a new one that behaves more appropriately.”

“MS robbed me of my ability to climb, ski, and walk. I said ‘I’m going to take a chance.’”

— John Chafe

Replacing his immune system was a rigorous procedure. John would undergo intensive chemotherapy to help eliminate his immune system. In November 2001, he was given a dose of chemotherapy to stimulate and move his stem cells into his blood stream. These stem cells were then collected and cleansed of any traces of MS.

A month later, John was given huge doses of chemo in an attempt to destroy his immune system and started getting weaker and weaker. On December 13, 2001, after the chemo had wiped out his immune system, John had the cleansed stem cells re-infused by an intravenous drip.

“I didn’t feel better immediately,” said John, who was only the second patient in the world to undergo a stem-cell transplant of this kind for multiple sclerosis. “But I started getting stronger in the days following, so much so that Dr. Atkins released me on Christmas Eve.” He spent three months living with his parents while he recuperated. By spring, he was ready to move back into his own home again.

Groundbreaking research in Ottawa

Dr. Freedman said that he and Dr. Atkins had anticipated that by rebooting MS patients’ immune systems, they fully expected the disease was going to restart.

“At that time, genetic researchers said, ‘If people are genetically prone to develop MS, there’s nothing you can do to stop it. They’re going to keep redeveloping MS,’” said Dr. Freedman. “If that was true, it would be a matter of time before people started having active disease again.”

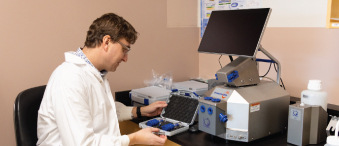

Dr. Freedman explained that nobody knows what causes MS. He and Dr. Harold Atkins hoped that through the trial they could reboot a patient’s immune system and monitor it with all the latest immune system monitoring and imaging technology, and then watch as the disease restarted and discover the secret of what triggers MS. However, none of the 24 patients in the trial developed new symptoms of MS again.

“In that respect, the trial was a failure. It halted their disease and in some cases their disabilities went away too,” said Dr. Freedman. “We’ve followed these patients for 18 years, and nobody’s developed anything.”

“Those patients at the beginning, like John, are probably the bravest because there were more unknowns about the treatment,” said Dr. Atkins. “Each patient we’ve treated over the years has taught us something, but we learned more from the early patients at that time.”

A second chance at life

Prior to his stem cell transplant, John had a final exacerbation, which crippled him. After the transplant, his MS did not return. John remained healthy, but the damage caused by the disease wasn’t reversed and he still walks using a cane and walker.

“You almost wonder what would’ve happened to John if he’d had the transplant five years earlier,” said Dr. Freedman. “Today, when we see a patient that has the same profile as John’s, we offer them the stem cell treatment. We’re not waiting years. We’ve become more savvy, able to pick out individuals who warrant this aggressive approach.”

About 77,000 Canadians live with MS. However, only five percent of patients with MS warrant a stem cell transplant. They are generally young and have the most aggressive and debilitating forms of the disease.

After his transplant, nothing was going to hold John back. Three years later, he met Patricia, and they married in 2005. Five years later, his beautiful daughter Mary was born.

“I recall that as Mary started moving more, she motivated me to get more active again. She became my personal trainer,” said John. “I joined the Canadian Association of Disabled Skiing. I was terrible at first because I didn’t have the strength. But I’m stubborn and refused to give up, and today I can ski independently for hours – albeit with outriggers for balance.”

“I saw John a few years ago. The problem with this business is patients get better and so I don’t see them much afterwards,” said Dr. Atkins. “I do remember him showing me pictures of his young baby, and pictures of him on the ski slope. It is exciting to hear that people can have these treatments and go skiing again.”

“I’m not a bank president, but my life is better than incredible. I ski, I dance with my wife, and have an nine-year-old daughter. Because Dr. Freedman and Dr. Atkins were persistent about finding the answers to stop a disease like MS, they saved my life.”

— John Chafe

The following video focuses on Jennifer Molson who was also one of the early patients on the MS clinical trial, and includes interviews with Drs. Atkins and Freedman.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.