Making great strides in the lab or on the dance floor

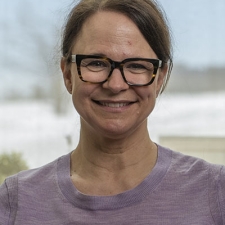

Meet Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre — sepsis researcher and clinician extraordinaire

Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre’s path to The Ottawa Hospital wasn’t necessarily a direct one — it took her all over Ontario and out west to the mountains — but she couldn’t do her groundbreaking sepsis research anywhere else, or with any other team.

Today, Dr. McIntyre balances her role as a critical care physician working clinically in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and with her role researching sepsis as Senior Scientist in the Clinical Epidemiology Program.

Keep reading to learn what Dr. McIntyre moved out west for, why she came back, and what exciting new support her research recently received.

Q: Can you tell us a little about your background and early years?

A: My father was in sales, and so we moved around a lot. I was born in Sudbury, then we lived in Winnipeg, Montreal, and Toronto.

A big part of my early life was figure skating. Skating was sort of dominant until I was 14, when due to long term injuries, I had to stop. I also grew and became five-foot-nine, which is not so compatible with skating!

Q: Did you always know you wanted to study medicine?

A: From a very young age, I knew I wanted to do medicine. I started volunteering when I was young. At 15, I started volunteering at a spinal cord centre in downtown Toronto and did that through high school. I guess I always knew I wanted to be in some kind of helping profession.

But I was a bit of a “free spirit” when I was younger — and maybe even now! I needed to just go live in the world for a bit first. So, after my first degree in Guelph, I diverted and went out to Whistler and taught skiing for a year and a half. Then I went back to school, I got into medical school and went to McMaster.

Q: What made you settle in Ottawa and here at The Ottawa Hospital?

A: I came to Ottawa to do my internal medicine residency, then went back to Vancouver for my critical care fellowship, and finally, came back to Ottawa for my research fellowship and to do my masters in epidemiology.

Coming back to an established critical care research environment with really successful and collaborative scientists was super important to me. The clinical environment in the hospital’s ICU is like my second family.

"The clinical environment in the hospital’s ICU is like my second family."

— Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre

Q: Can you describe your current work at The Ottawa Hospital?

A: I am an ICU physician, or intensivist, looking after critically ill patients. And the other major part of my career is research, which over the years has focused on studying resuscitation and the stabilization of patients that have very severe infections in the intensive care unit.

For the first several years of my career, I really focused on the fluids we use in the ICU — which we use every day and have been around for decades. I was trying to figure out whether one type of fluid was superior to the other, and whether they could help our acutely ill patients and those with sepsis and septic shock survive.

More recently, I’ve been focusing on the study of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for the treatment of septic shock. This program of research is super collaborative, and we collaborate with an internationally recognized group of critical care investigators called the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. It’s really inspiring to work and collaborate with so many different sepsis critical care minds in Ottawa and throughout Canada.

Q: What exactly is sepsis?

A: Sepsis is caused by an infection, a bug — be it bacteria, virus, fungi. Many of us will get these bugs, and we’ll do fine. We’ll get a cold or maybe we’ll get a mucousy cough, and we might feel like hell for a couple days, but we recover from it. Sepsis occurs through our body’s response to that infection, and it, in part, will determine the severity of that infection. If how your body responds results in the failure of one or more organs, we call that sepsis. And if the infection becomes even more severe and causes shock, we call it septic shock.

Some of this is a result of the genes you have, your genetic makeup, which can affect how you respond to a given pathogen. Other things, like how many other chronic illnesses you have, can also affect the severity with which you respond to an infection. There’s also environment, diet and physical fitness, and other external factors that can have an impact.

You can pick up a bug externally, through an open cut, but you can also breathe it in like we do with COVID, influenza, or RSV. There are other ways, like through the urinary tract or the digestive tract, the latter of which has millions and millions of bacteria and fungi that live there even when we are healthy. But where bugs can wreak havoc is when they get into the blood stream.

"The only way we can do research in ICU settings is to have funding to support the research team and the research engine — meaning the manufacturing of stem cells and the recruitment of patients that make the research go."

— Dr. Lauralyn McIntyre

Q: You were awarded $1.3 million from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and $1 million from the Stem Cell Network to conduct a Phase II clinical trial of MSCs in patients with septic shock — can you describe what this funding will help with and why it’s so important?

A: The UC – CISS II trial follows on an earlier study (CISS I) that suggested mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are safe when treating patients with septic shock. We saw some signals to suggest these cells also affect inflammatory markers in our blood stream that are related to sepsis. MSCs might hold immense therapeutic promise for the treatment of sepsis, because in animal sepsis models they seem to balance out the immune system again. We’re studying introducing MSCs when patients are in the very early phase of sepsis, when the immune system’s cascade response is peaking, to try and blunt the severity of this immune response.

The only way we can do research in ICU settings is to have funding to support the research team and the research engine — meaning the manufacturing of stem cells and the recruitment of patients that make the research go. Having this $1.3 million from CIHR and the $1 million from the Stem Cell Network has provided us with sufficient funding to really do an awesome trial. We’re good to go. We are just so grateful that our funding agencies believe in us, and we will follow through.

Q: Christine Caron was treated for septic shock at The Ottawa Hospital in 2013, and she has since become a patient partner in your research. What makes patient partners so important to your work?

A: Working with patient partners has been illuminating in many ways, and in particular regarding post-sepsis survivorship. In critical care, especially in clinical trials, we used to just focus on improving survival — at 28 days, three and six months, maybe out to a year — which is incredibly important. But there has been much less emphasis on the quality of that survival. Sometimes, patients (and their families) feel like they’ve been abandoned by our healthcare system; they receive care in the ICU and then the hospital wards, and then after they’re discharged, they’re on their own to follow up with their health care provider in the community, if they are fortunate enough to have one.

Patient and family partners really help us understand, as researchers, what aspects of quality of life are affected by experiencing a critical illness — and which aspects are most important to people in their lives. Working with these partners really inspires me to do the most rigorous research to answer scientific questions that will have a positive impact on patients’ lives.

Q: What would we find you up to when you’re not in the clinic or lab?

A: I love being outside, in the bush, just going for hikes. You could call the forest my soul food. I love not hearing anything, just being. We have a cottage in Tenaga (near Chelsea, Quebec) where a lot of my hikes span from.

Over the last couple months, I’ve also started ballroom dancing. There’s a very similar joy that I had when I figure skated. It’s just incredible; it feels like I’m on the ice again. Dancing for me is also like a therapy, as it has helped me with my grief after the loss of my husband Christopher, who died of cancer in 2021.

Besides that, the other big thing I love to do is spending time with my family — my daughter Maia and my dog Kiko, extended family, cousins, and dear friends. There are eight McIntyre families, all my dad’s siblings, who grew up in Ottawa. Several of the siblings and then their kids (my cousins) and their kids’ kids spend the summer in Tenaga at the cottage — the McIntyre’s go back there for over 100 years. Every summer, we’re all together, and it’s the most beautiful thing.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.