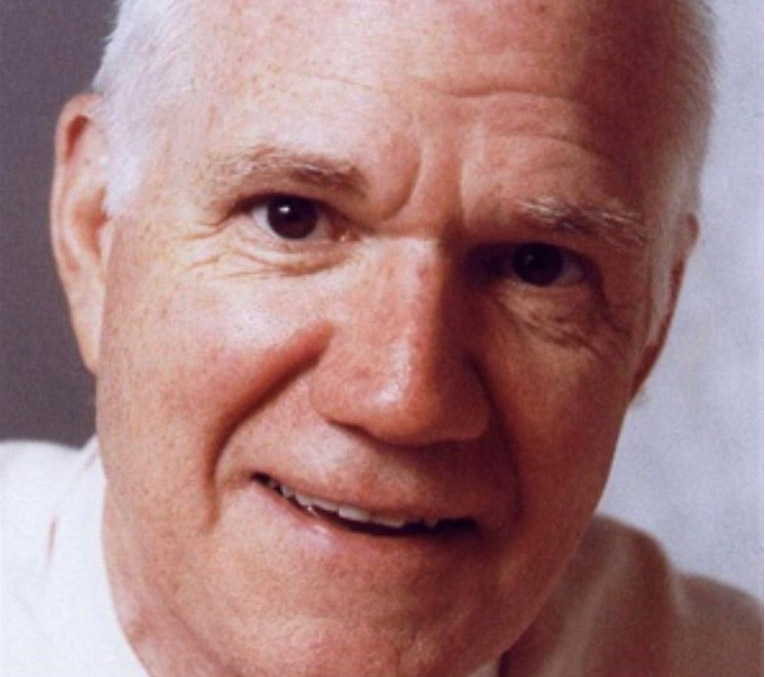

At the start of his career in the mid ’90s, Dr. Tien Le was the only gynecologic oncologist for the entire province of Saskatchewan. Today, he’s one of about 40 gynecologic oncologists in Ontario reshaping gynecologic cancer care. Dividing his time between delivering care to patients and conducting practice-changing research, this academic Gynecologic Oncologist and Scientist at The Ottawa Hospital brought his skills home to Ottawa in 2002 to join a dynamic, multidisciplinary oncology team committed to delivering the best cutting-edge longitudinal cancer care for women with gynecologic cancers.

Find out how the field of gynecologic-oncology has drastically changed since Dr. Le’s early days on the Prairies and what he’s most excited about today.

Q: What were your early years like?

A: I grew up in Ottawa, but I originally emigrated from Vietnam as one of the “boat people” when I was five. I went to Glebe Collegiate, where science was my favourite subject. I was always drawn to physiology and an understanding of how things work.

Outside of school, my hobbies were mostly writing code for computer games and learning about computers. Back then, we still had dial-up internet access. Coding helps you think about problems in a defined stepwise manner and solve problems logically. Learning to apply that method to my work today has been very productive and rewarding. I do a lot of my own data analysis and statistics as I pursued a degree in epidemiology and biostatistics after my fellowship.

Q: How did you decide to pursue medicine?

A: Back in Vietnam, my father was an ophthalmologist, but when we moved here, he worked as a family practitioner, so I got some exposure to medicine in my early years.

When I applied to university, I knew I wanted to do something healthcare-related, but medicine wasn’t particularly high on the list yet because the competition was very fierce. I did my undergrad in biochemistry and physiology at uOttawa, and at the time, I was considering a career in research or dentistry. During my first year of university, though, I became more and more interested in physiology and anatomy and how the different organ systems work together in health and disease. Eventually, I felt more drawn to apply this knowledge to disease management. I realized medicine would be the perfect fit and was accepted to the University of Toronto medical school after only two years of undergraduate study.

Q: What drew you to gynecologic-oncology specifically?

A: Back when I was in medical school, women’s health was a relatively underdeveloped specialty. I saw a lot of opportunities for research and personal growth. During my obstetrics and gynecology residency at the University of Manitoba, the program was strong in gynecologic-oncology. The program director, Dr. Garry Krepart, was one of the founders of the subspecialty in Canada. The field continued to grow on me as I progressed through my residency because it was the perfect marriage between surgical oncology and medical oncology, which is unique to this subspecialty.

Q: How has the field of gynecologic-oncology changed since you started out?

“Patients continue to live longer with a better quality of life.”

— Dr. Tien Le

A: The field is advancing very rapidly, and there have been huge advancements in the field of gynecologic-oncology since I was in medical school. For example, when I was a medical student, the median survival for a patient with advanced ovarian cancer was not even 12 months. When I was a resident, it had increased to two years. Now, it is five years, and patients continue to live longer with a better quality of life. All this can be attributed to better therapeutic strategies, including surgery, chemo, and the use of maintenance therapy. For example, for ovarian cancers, the use of PARP inhibitors (an oral tablet called Olaparib/Niraparib) that can keep the cancer in remission is now commonly recommended.

With ovarian cancer, while oncologists have been very successful at pushing the cancer to remission after primary treatment, most patients with an advanced stage of disease will have their cancer recur. More and more, we’re looking at ovarian cancers as a chronic disease, like diabetes or asthma, where we have effective therapies to manage these chronic conditions.

Q: What is the most exciting research currently happening in your field?

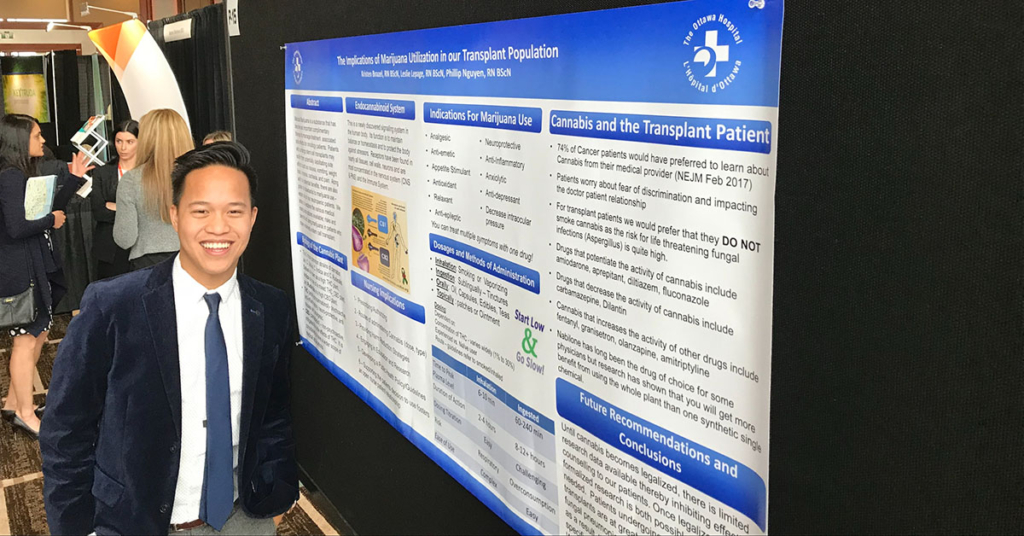

A: Running clinical trials is an essential component of all oncological practices because it’s how we identify the most effective therapies and offer the most cutting-edge treatments for specific cancers. At The Ottawa Hospital, we’re currently running a number of trials on ovarian, uterine, and cervical cancers.

Specifically for ovarian cancers, we’re studying a new class of medication called antibody drug conjugate, or ADC. ADC is made up of an antibody that links to an active drug that’s toxic to cancer cells. It’s like a magic bullet or Trojan horse: the drug only gets taken up by the cancer cells, leaving normal cells unaffected.

The other therapy that’s been causing a lot of excitement in the gynecologic-oncology community is immunotherapy for the treatment of uterine and cervical cancer. It works very differently from traditional chemotherapy in that immunotherapy stimulates a patient’s immune system to seek out and destroy cancer cells. It’s been very effective, and we routinely use it for metastatic, advanced uterine and cervical cancers.

Finally, another therapy we’re using here at The Ottawa Hospital is hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). During the treatment, we administer heated chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity during surgery. It’s been shown to prolong survival in patients with ovarian cancer. The Ottawa Hospital is only the second hospital in Ontario to provide this treatment.

Q: What made Jennifer Hollington’s cancer journey unique?

A: Jennifer is the perfect example of our longitudinal, multidisciplinary model of care. She was initially diagnosed with a large pelvic mass, and her gynecologist referred her to our gynecologic-oncology team at the General Campus. I ended up being the surgeon who performed the surgery. She was subsequently treated with chemo, receiving support from our extended team of nurses, pharmacists, residents, fellows, and allied healthcare professionals during her cancer journey.

After genetic tests on the tumour revealed that Jennifer had the BRCA2 gene mutation, which increases the risk of both ovarian and breast cancers, she decided to get a preventative mastectomy. This knowledge also helped shape her ovarian cancer treatment. Olaparib is especially effective in those with this BRCA2 gene mutation, so we started her on this maintenance strategy personalized to her tumour profile.

Jennifer also had melanoma, which was an unlucky coincidence, and our care team supported her through that as well.

Something to keep in mind about ovarian cancer is that it’s a relatively rare cancer compared to breast, colorectal, or lung cancers — the three most common cancers in women. Women with ovarian cancer often have very nonspecific symptoms that don’t always clue them into the cancer diagnosis right away. The nickname for ovarian cancer is “the disease that whispers” — it’s a silent killer that is typically asymptomatic in the early stage of the disease. By the time symptoms occur, the cancer has often already metastasized. At this stage, it is much harder to cure and treat. It is important to emphasize that if a patient is facing unexplained, persistent symptoms — such as pelvic pain, abdominal pain, increased abdominal size, bloating, difficulty in eating and a feeling of fullness, or urinary urgency and frequency — they should seek medical attention right away and not ignore these symptoms.

Q: How does community support for research help patients?

“Together with community support, we can work together to advance and improve care for our patients in Ottawa region.”

— Dr. Tien Le

A: The development of new therapies and the incorporation of new technologies takes money. Ongoing community support for The Ottawa Hospital’s mission has been wonderful. Speaking for my department, through donations we were able to bring robotic surgery to gynecologic-oncology patients undergoing uterine cancer surgeries. This technology allows the surgeons to see better and patients recover faster and with fewer complications after surgery. It results in huge savings for The Ottawa Hospital as well, with shorter inpatient hospital stays and fewer post-op complications to manage, which allows us to use the money for other things to improve patient care. For the robotics program, unless we had donations, we would never be able to bring this technology to our patients. It’s a costly machine. Together with community support, we can work together to advance and improve care for our patients in Ottawa region.

Q: Why did you choose to work at The Ottawa Hospital?

A: I love our model of care: it’s patient-centred, longitudinal, and multidisciplinary. A personal reason why I have been here since 2002 is the camaraderie among all team members. We have a very good team in gynecologic-oncology in Ottawa dedicated and committed to care for our patients. We work in a collaborative, friendly environment — physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and allied healthcare professionals all doing what we enjoy doing and helping patients under our care.