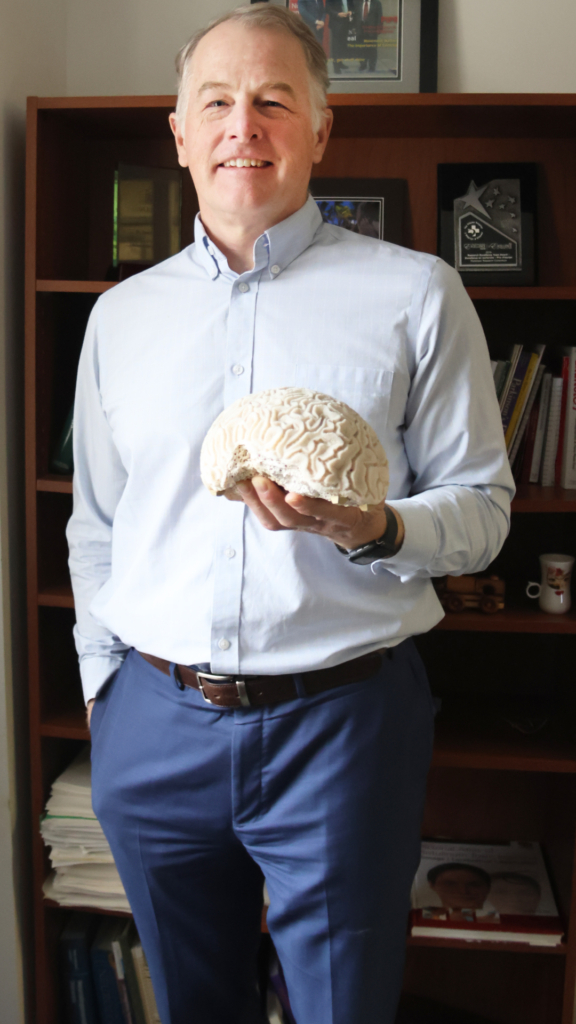

Endometriosis is a common condition, but Dr. Sony Singh’s dedication to improving endometriosis care is anything but common.

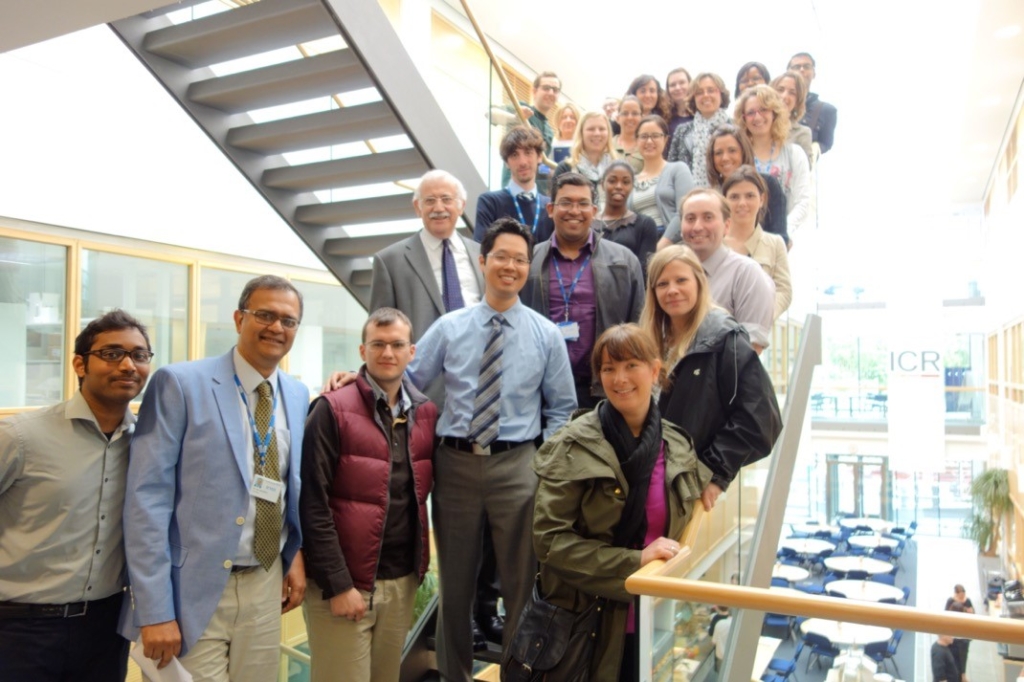

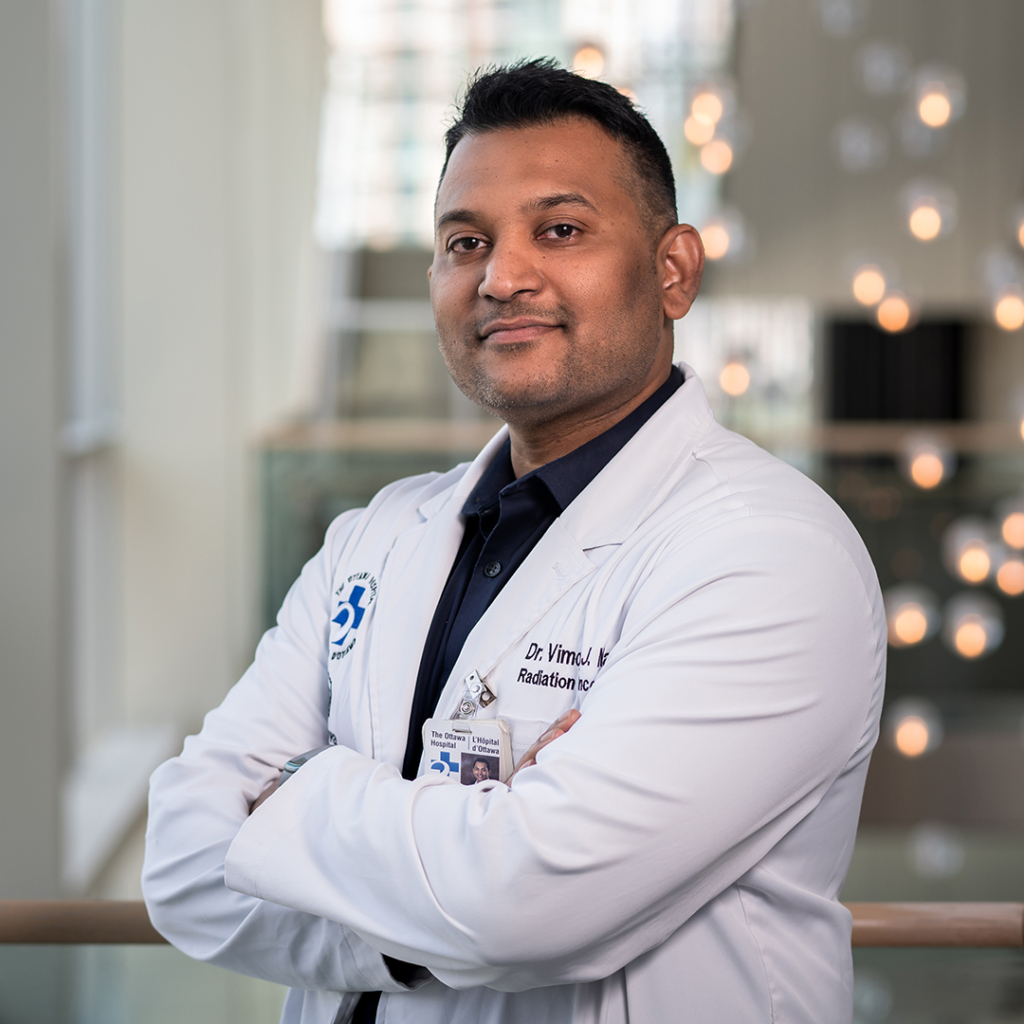

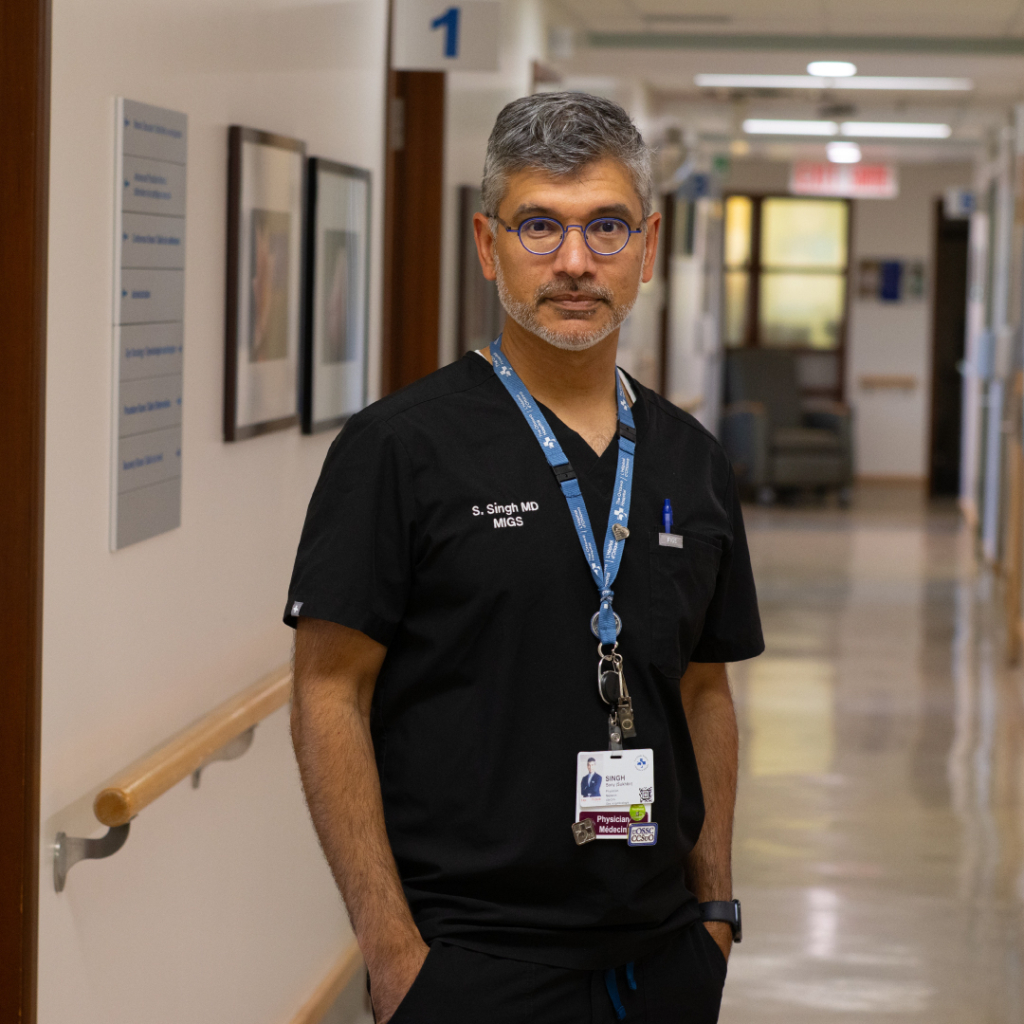

As an Associate Scientist and Department Head for the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Newborn Care at The Ottawa Hospital, he is changing the way we diagnose and treat endometriosis. For the millions of women in Canada suffering from the condition, Dr. Singh’s minimally invasive surgical approaches, advanced imaging, and practice-changing research promise a bright future with better care.

Find out what sign convinced him to pursue obstetrics and gynecology, and what might surprise you about endometriosis.

Q: What were your early years like?

A: I grew up in the Toronto area and then moved out to Brampton, where I attended high school. My parents had humble beginnings and were both factory workers.

Growing up, my biggest hobby was advocacy. As a teenager, I got involved in my high school’s environmental club, way back in the late ’80s and early ’90s. I was also the student council president, and I was always trying to advocate for racial and ethnic diversity at a time when we were just starting to understand the topic.

Q: Who were your biggest influences as a youth?

A: I had strong women role models in my mom, my grandmother, and several high school teachers. My grandmother inspired me so much as someone who couldn’t read or write, was married at 14, had none of the privileges anyone else had, and had nothing to give other than pure love. She lived until 100! I realized very early on that society wasn’t treating women with the same respect as they would men.

Q: What did you want to be when you grew up?

A: I didn’t picture doing medicine! I pictured doing some sort of leadership in the community, maybe being a police officer or running a not-for-profit.

Q: When did you decide to pursue medicine?

A: In high school, I fell while rollerblading and had a huge laceration on my right leg — I still have the scar! Rollerblades had just been introduced, and I took them down a hill and decided to jump on some grass and slide down, but I fell right on a broken beer bottle. I remember going to the emergency room in Brampton, and as the doctor was sewing it up, I was just fascinated by him cleaning it up and taking care of me. That was the day I first thought of going into medicine.

In my undergrad, I did Life Sciences at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and I was doing quite a bit of work in research, working with animal models to look at infertility care and how stress causes difficulties getting pregnant. I also did some work in orthopedic trauma surgery. That’s when I knew I wanted to go into medicine, and I applied and got into medical school at Western University in London, Ontario.

Q: How did you decide to specialize in obstetrics and gynecology?

A: I had an interest in women’s health early on, and I was drawn from a young age to speak up against injustice and join whatever support I could for women. And at Queen’s, I ran something called their sexual health resource centre, and we focused on education around women’s health and advocacy.

During my undergrad and at Western, I was considering obstetrics, but I was also thinking about doing family medicine.

Then, in my fourth year as a medical student, I was visiting my sister-in-law, and she went into labour. Suddenly, she said she felt pressure, then she said, “It’s coming!” As a medical student, I knew what to do, and I delivered my niece right there in the bathroom.

I really needed a sign, and this was the sign that made it clear that obstetrics and gynecology was what I wanted to do. My niece is now doing their master’s at the University of Ottawa!

Q: Are you a superstitious person?

A: I would say a little bit. I think there’s a reason for everything. I’m not religious, but I’m spiritual, and I think a lot of things that happened to me nudged me in the right direction.

Q: What exactly is endometriosis?

A: Endometriosis is a common condition that can impact women and people with uteruses. It is tissue like the lining of the uterus, but growing elsewhere in the body, often resulting in pain and/or difficulty getting pregnant.

Q: What is something unusual or surprising about your field of study?

A: Something I wish people knew about endometriosis is that it can affect almost every system of the body. I developed an expertise in endometriosis during fellowship training in Toronto and Australia back in 2005–2007, and at the time very little was known about the disease — despite the fact that it’s been around for a millennia.

“It’s a real once-in-a-lifetime privilege to advance the treatment and diagnosis of it here, locally.”

— Dr. Sony Singh

It’s a fascinating disease impacting millions of women, but we’re just at the beginning of understanding endometriosis. It’s a real once-in-a-lifetime privilege to advance the treatment and diagnosis of it here, locally. But we have so much further to go.

Q: How has our understanding of endometriosis changed since you first started out?

A: The biggest gain has been greater awareness amongst the public, because education is key. Back in high school, when we talked about periods, we didn’t learn anything about endometriosis. Today, they’re learning about that in high schools.

The second big development has been in imaging. The ability to do higher quality imaging is helping us pick up the disease better.

“We’ve not only built this program here at The Ottawa Hospital, but we’ve taught others, and it’s expanded far beyond us.”

— Dr. Sony Singh

Third, I’m now able to learn and teach more advanced surgical techniques to help manage this disease. Our fellowship that I started here around 2008 has produced some of the best endometriosis experts working in Canada. We’ve not only built this program here at The Ottawa Hospital, but we’ve taught others, and it’s expanded far beyond us.

Q: What would your advice be for someone recently diagnosed with endometriosis?

A: I’d tell them they’re not alone. That this is a common condition and that their pain and experience are valid. Getting access to care is a number one priority, and we have excellent care in terms of diagnosis and treatment. I’d also tell them they have to advocate for that care, because our medical system is still struggling to understand the disease; getting help can be tough, but keep on fighting to get that access.

Q: What made your recent case with Danika Fleury special?

A: Danika’s case is actually quite common in that she had a delayed diagnosis. There are so many women like Danika struggling out there with endometriosis but not getting a diagnosis. The time between symptoms and receiving care was seven years before the pandemic, but after the pandemic, it got worse. This delay is due to a lack of education, guidance, and information at the primary care level, and a lack of access to specialists who can manage it once it’s diagnosed.

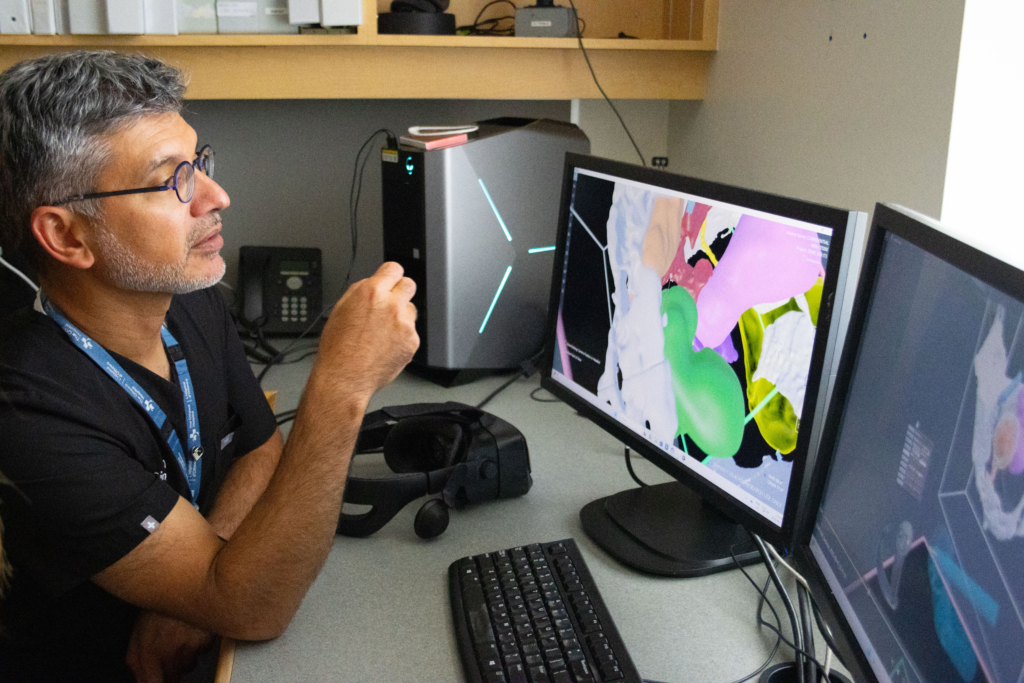

Once we saw Danika, though, we were able to use advanced imaging expertise, thanks to a new radiologist we recently recruited. It’s a disease that’s just supposed to be “period problems,” but we were able to see that her endometriosis was invading her pelvic nerves, and that’s why she was having difficulty walking and moving. It caused significant damage to her muscles on the left side of her body. We also created a 3D image to use in a virtual reality model to help me and my team practice and understand where the disease was so we could target it while minimizing harm to surrounding tissues.

It really illustrates that the future is bright for those struggling with endometriosis and people like Danika.

Q: How does community support help your patients?

A: Community support is where this all started. About 15 years ago, we got donations from Shirley Greenberg herself and some other community donors, and it raised $1 million to advance minimally invasive gynecology at The Ottawa Hospital. That set the trajectory for the hospital becoming a leader in minimally invasive surgery. We were able to build this incredible program with amazing colleagues. Community support allowed us to get the equipment and move things forward, and it has continued to allow us to increase our education and continue our work.

Next, I want to create a centre of excellence for endometriosis with provincial and federal funding to help lead a network of endometriosis research and care across Canada.

Q: What does your current research focus on?

A: I currently have several layers of research: the basic science (why this happens, how to prevent it, etc.); clinical research (what’s the patient experiencing, how to use imaging); clinical trials (which medical therapies work best); and working with other disciplines to find broad solutions.

It’s really a multidisciplinary disease that requires a multidisciplinary approach; I’ve worked with every surgical and imaging expertise in the hospital for this condition.

Q: What’s your favourite part of working at The Ottawa Hospital?

A: The people. I’m so proud to be working at The Ottawa Hospital. It’s a culture I came into in 2007 that prioritizes the patient experience, quality of care, and excellence. This flows through every level, from the clerk you meet to the volunteer down the hall to the nurses in the clinic to the healthcare providers. There’s no other place I’d rather work. When I walk into a patient room, it’s all about them, and they know we want to help them. I remind myself to be grateful all the time.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not at work?

A: On the water on a kayak or on a bike on one of the many trails in the city. I am first and foremost a father and a husband, and I have three wonderful teenagers and a wife who’s an engineer.