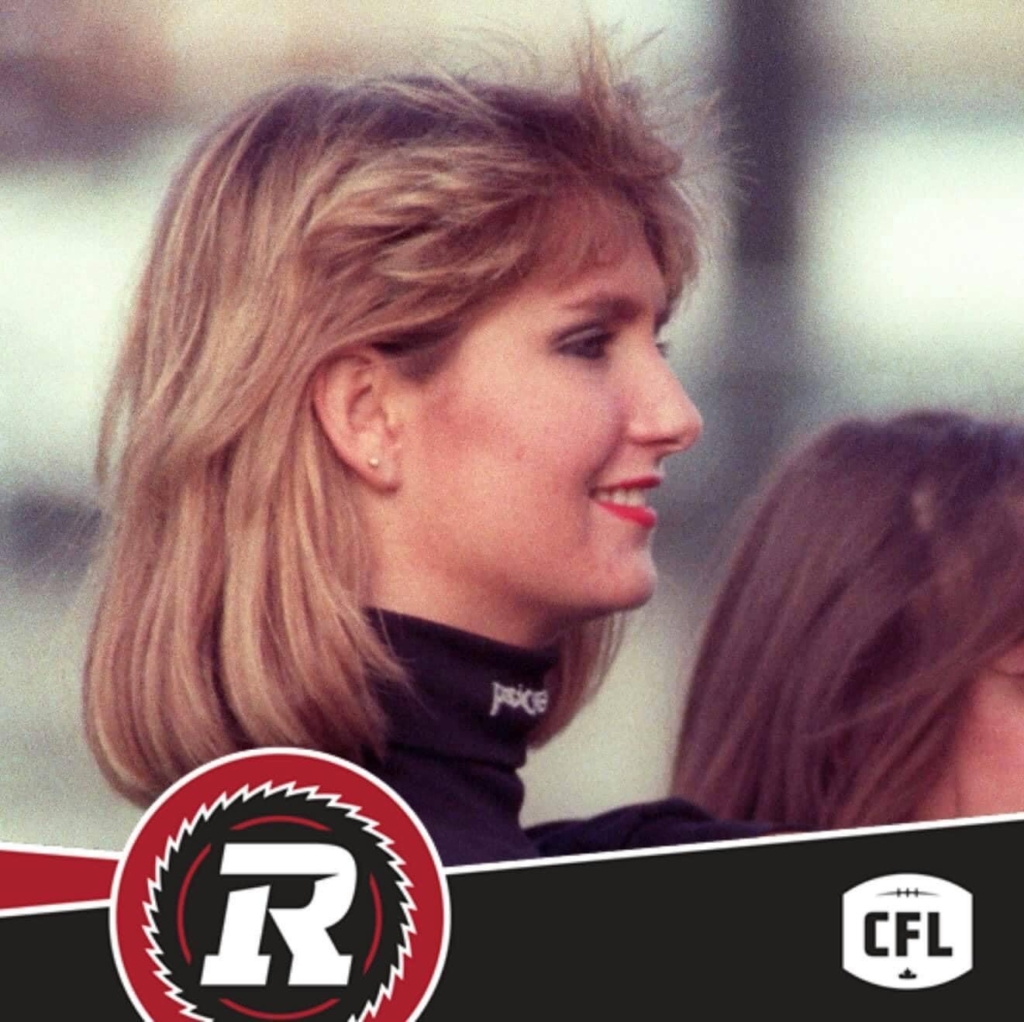

A chance encounter can change a life, or it can change countless lives. When Linda Powers first needed a physiotherapist, it was to help with her knee issues from years of intense cycling. She went on to become a physiotherapist herself, one who teaches people to walk again — among other things — after a stroke.

Linda is now semi-retired after working out of The Ottawa Hospital for 28 years, with 22 of those years specializing in neurology physiotherapy. She dedicated her career to helping make the connections between mind and body that allow patients to regain independence and motion following life-changing neurological events, like stroke.

Find out who set Linda on her course in life, why she fell in love with physiotherapy, and how important community support is for the patients she works with.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your early years?

A: I was actually born at the Civic Campus of The Ottawa Hospital. At a young age, my parents moved us to Gatineau, which was interesting because we were an English family in a very French community. In those days, there weren’t many options for women or young girls in sports, but I found my love of exercise through cycling and through dance — not competitive, because we couldn’t afford that, but through cheerleading.

Q: What did you want to be when you grew up?

A: A model! Or a flight attendant. My father worked for Air Canada, and I remember thinking that was the coolest job ever, to be flying everywhere for free. Later on, I thought I might go into computer science. I didn’t even know physiotherapy was a thing back then!

Q: When did you realize you wanted to become a physiotherapist?

A: In elementary school, I didn’t realize I was smart. I remember being in Grade 8 and trying to choose my path for high school, we had to choose secretarial or science. I was afraid of science, and all my friends were choosing secretarial, so I did too. But I had the most incredible guidance counsellor on the planet who called my parents and said, “your daughter is throwing away an intelligent mind. Please convince her to go into science.” Of course, I did. I literally would not be where I am today if it hadn’t been for that one woman — Mary Lou McGuire.

After studying science in CEGEP, I went into biology at the University of Ottawa, where I specialized in exercise physiology because I loved exercise and because the physiology part is incredible and it still to this day interests me.

My first experience with physio happened because I had knee problems, which it turns out came from being flat footed and very active! I remember to this day sitting on the table, getting my knee treated, and talking to the physiotherapist about the field. I remember thinking, “Wow, what an amazing job. You’re getting paid for something you love!”

I’m extremely lucky I came across physiotherapy, because even though work can be busy and stressful, I still have moments every day where I feel lucky to have the ability to give this gift to somebody.

Q: How did you wind up in neurology physiotherapy?

A: During my physiotherapy degree, I started looking at all the different fields I could work in. I had three out of six placements in neuro, and I loved helping people regain some mobility. When you graduate, you don’t usually get to immediately work in your field of choice. So, I started in an orthopaedic clinic, but I didn’t stay there long. I quickly moved to a clinic with home care, where I could work with neuro patients and patients with cardiorespiratory issues. After just a year and a half, I got hired at The Ottawa Hospital, where I floated around for a bit working pretty much every unit, before settling in neuro. I spent 22 years in neuro before retiring in 2023, and now I work casual, taking as many shifts as I can on the neurology unit.

Q: How does your unit differ from rehab physio?

A: In many physio fields, you’re working with one body part. With orthopaedic physiotherapy it might be a finger or a knee, and with cardiorespiratory physiotherapy you’re working with the breathing system. With neuro, you’re dealing with multiple systems, overall mobility, and anything the brain and spinal cord control. We basically become brain experts. For me, it was the most challenging, the most interesting, and the most rewarding.

“It’s a rush of endorphins, like finishing a race.”

— Linda Powers

The largest diagnosis in neuro is stroke, and with stroke, we’re trying to get the patient to walking as an end point. We start with moving in bed, learning to sit, holding balance, and eventually walking.

You apply treatments and you see effects, and it’s just incredible. It’s a rush of endorphins, like finishing a race.

Q: You worked on Sophie Leblond Robert’s case; what made it challenging or unique?

A: Sophie had a brain stem stroke, where there was a massive clot in her posterior artery, which comes up through the spine. It’s a serious location, because it can shut off a lot of your automatic functions, like heart rate or blood pressure control, or it can break the connection between your brain and body, which means you can wind up with locked-in syndrome. You generally only have your thoughts and the ability to move your eyes.

Because of the extreme nature of Sophie’s stroke, she had locked-in syndrome.

“Linda, we had another miracle come in!”

— Linda’s colleagues

Our interventional radiologists removed much of the clot using endovascular therapy (EVT) — a minimally invasive procedure. I’m always in awe of our interventional radiologists and how they save people. I call it the miracle of EVT. Other therapists will joke, “Linda, we had another miracle come in!”

After her surgery, Sophie just had an incredible recovery. When I first met Sophie, she had barely any movement in her limbs and a hard time moving her eyes. If she moved her eyes a certain way, she’d get very dizzy, and there would be a lot of nausea. With her initial mobility assessment, she couldn’t even hold her balance sitting at the edge of the bed. But fast forward, and she started making gains really quickly. She wound up taking her first steps within just a few months, on October 1! People don’t often recover from locked-in syndrome — Sophie was a true exception

Q: How does community support ultimately help patients like Sophie?

A: Without community support, we wouldn’t be able to do the research that develops things like EVT, which saved Sophie. At the beginning of my career, EVT wasn’t a thing for stroke. They used it to get clots out of coronary arteries, but using it for strokes was a game changer.

Community donations also help support research into hyperacute medical care, which has shaped how we identify a patient coming to the ER with a possible stroke. Community support even goes towards the technology our doctors use and can help allied health by improving staffing levels and helping purchase the equipment we use in physio, such as walkers or special chairs for our neurological patients.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not at work?

A: You might find me on my bike or walking my dog, Leroy — he’s a shih tzu, lhasa apso, poodle mix. I get out hiking with him every day. I also have a son, Matthew, who’s 25 and studying engineering at Carleton University. I raised him alone, so we have a very special bond. I love spending time with him whenever we can carve out time for each other. I’m now an empty nester and partially retired. Give me a bike and a dog park and some good friends, and I’ll be happy.