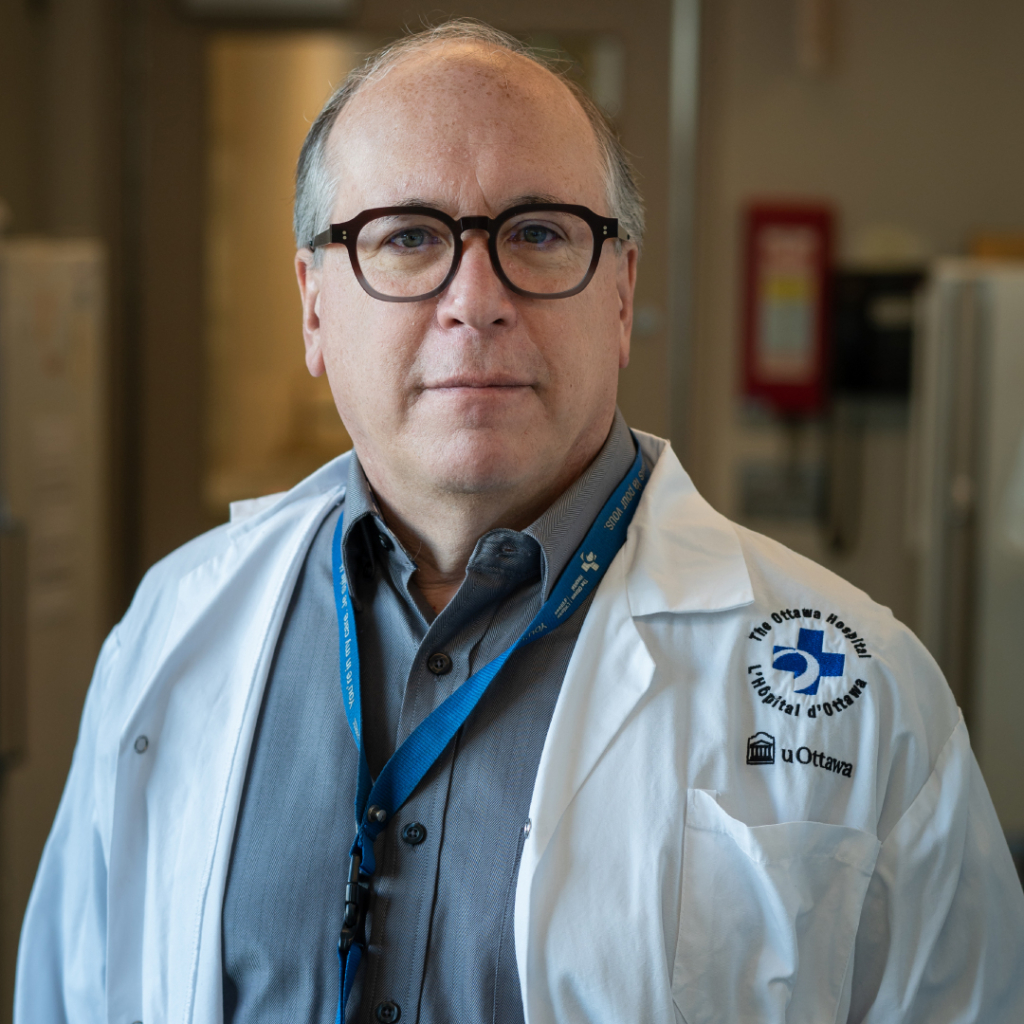

Dr. Jay Baltz’s career and the first test-tube baby are about the same age. When the senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital first started in his field, researchers were struggling with a puzzle that was blocking the progress of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Through pioneering research and his work with one of the creators of IVF, Dr. Baltz would go on to push fertility science to new heights and help make the field a breeding ground for innovation.

Find out when the first test-tube baby was born, how fertility science has changed since, and which 17th century textbooks Dr. Baltz still uses.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your early years?

A: I’m from Philadelphia. I was born there, and I was there through university. I was always interested in science. I had a chemistry set, and those were the days of the space program and the moon landing, so every time NASA launched a rocket, I was glued to the television set.

Q: How did you choose to pursue biophysics?

A: Early on I was interested in physics and the hard sciences, but it wasn’t really until I was finishing up my undergraduate degree at the University of Pennsylvania that I became interested in applying that to biology. At the time, biophysics had been around for a while, but it was sort of coming of age. It’s an interdisciplinary field that uses the theories of physics to understand how biological systems work.

I decided to do my PhD at Johns Hopkins in the Department of Biophysics, and then I completed postdoctoral training at Harvard Medical School.

Q: How did you wind up researching fertility specifically?

A: In my first year of graduate school at John Hopkins, we did rotations through several labs before picking our thesis lab. One of the professors was Dr. Richard Cone, who had been working on how photoreceptors in the eye work, but he was transitioning into working in reproductive biology. It seemed really interesting, and so I went into his lab around 1980, and my thesis was on sperm-egg interaction.

Q: What drew you to Canada and The Ottawa Hospital?

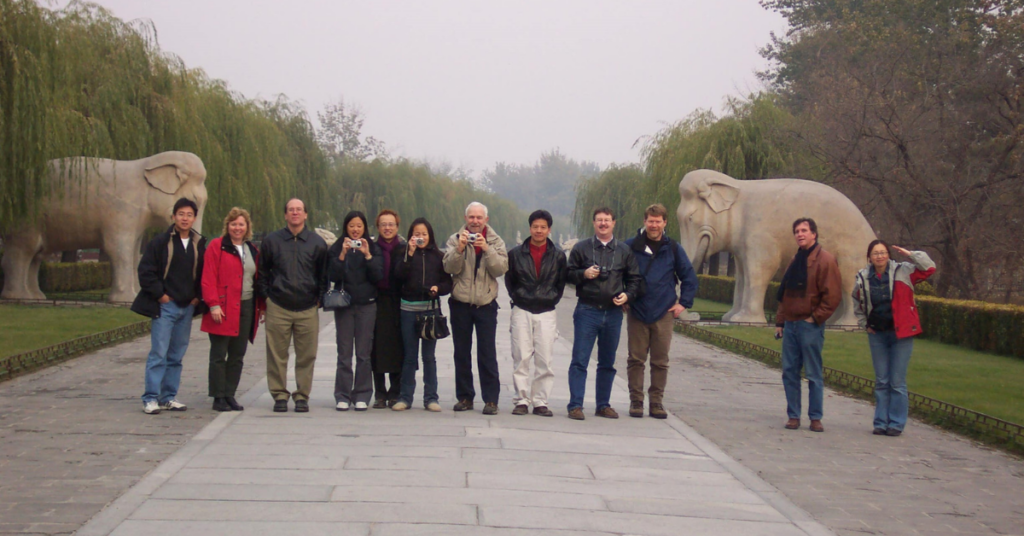

A: There were a number of places where I got interviewed and considered. I had been in Dr. John D Biggers’s lab at Harvard, and he was one of the creators of IVF and early embryo culture. I was looking in that area to pursue my research. Ottawa had a reproductive biology unit in the new, at that time, Loeb Health Research Institute — which has now become the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Dr. Benjamin Tsang was the head of the unit, and he recruited me to come up here. I had considered being a laboratory director for clinical IVF, but ultimately, I thought it was more interesting, and probably more useful in the long term, to do research on how to improve the conditions for early embryo development.

Q: How would you describe your research that won you the Dr. J. David Grimes Research Career Achievement Award?

A: I worked on how to grow very early embryos that are healthy. We were trying to determine what makes them as healthy as possible during the time they’re grown in dishes after in vitro fertilization, so when we put them back into the uterus, we can hopefully get a healthy baby.

As of 1978, we had the first test tube baby, Louise Brown. In those early IVF cases, embryos were transferred to the uterus when they were just four or eight cells, because we could fertilize eggs in vitro, but we couldn’t grow those up to the blastocyst stage, which is a hollow ball of about 32 cells. We wanted to be able to grow them to this stage to better select the healthiest embryos and improve the chance of a successful pregnancy.

At the time, we were studying mice, where we could fertilize an egg in a dish and grow it to the two-cell embryo stage, but further development was blocked. However, we could take a two-cell embryo out of a mouse, put it in a dish, and it would develop just fine up to the blastocyst stage. So, there was something about being outside of the female reproductive tract for the short period of time when the fertilized egg cleaved into two cells that stopped them from developing. Dr. Biggers’s lab was one of the first that figured out what that block was and at least one way to get past it.

I started looking at the differences between the culture media — the drops of liquid the embryos grew in — that we used in the dishes. We realized that the mechanisms that very early embryos use to control the size of their cells were not supported correctly by the media, so they did not develop. But giving them the newer media allowed the embryos to control their cell size and helped get them through those blocks to development and grow to a stage where they could implant in the uterus. As part of this research, we found that the ways early embryos control the size of their cells were different from those that other cells use. In a nutshell, we had to find out how these worked and make sure embryo culture media provided what they needed to function optimally.

Q: What does it mean to you to win the Dr. J. David Grimes Research Career Achievement Award?

A: It’s very gratifying to get a recognition like this. It’s humbling to join the ranks of people who have gotten it before. It recognizes not just my efforts and what I did but all the people who have been in my lab and who really did the work. It’s almost a cliché now, but it’s true that this award is due to them, not due to me.

Q: Looking back at how far fertility technology has come since your early days, what are some highlights for you?

A: The big change has been how common IVF and treatments for infertility have become. There are millions and millions of people worldwide now who have been born through IVF or associated technologies. In Canada and North American in general, a little more than 15% of couples are clinically infertile, so there’s a huge pool of people who need to have this available.

It’s very gratifying that things are working. It’s been great to have my career span from when this was really an experimental setup in the ’80s to now. It’s been good to see that the babies who were born 20 years ago now or more are growing up healthy.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not in the lab?

A: I’ve got a few things that have nothing to do with what I do at the hospital, but it’s sort of the same thought process as research. I’ve ended up getting involved in zoning and planning issues through the community association in our area and was recently appointed by city council to what’s called the Committee of Adjustment, which approves minor changes to zoning on a property or severance of properties into more than one lot. I also collect and restore rare books. Some are ones from the 1600s that I use for teaching, like William Harvey’s book on animal reproduction, which is one of the first to say all animals come from eggs, and Reinier De Graaf’s, which has one of the first descriptions of ovaries with follicles in it.