The uterus fits in the palm of Dr. Sony Singh’s hand. The large pink lumps inside the clear, plastic 3D-printed model are fibroids, or tumours, and there are more than 50 of them. To ensure his patient could carry a child in the future, Dr. Singh had to do something that had never been done before.

Maureen had suffered for years with abdominal pain. Over the past six years, she was told by five doctors that she had so many fibroids in her uterus, her only option was to have a hysterectomy – complete removal of her womb. She refused this option.

“I will die with my womb. Nobody will touch it,” said Maureen (who did not want her last name used).

She was referred to the Shirley E. Greenberg Women’s Health Centre at The Ottawa Hospital, where she saw the Minimally Invasive Gynecology team of doctors and nurses. Dr. Singh, who is a surgeon, associate scientist and former Dr. Elaine Jolly Research Chair in Surgical Gynecology (2016-2021), told Maureen he could remove all the fibroids, and she would not need a hysterectomy.

“Maureen had close to 50 fibroids and we wanted to make sure her uterus was able to carry a baby in the future and function normally,” said Dr. Singh. “But we needed help to plan the complicated surgery to remove them.”

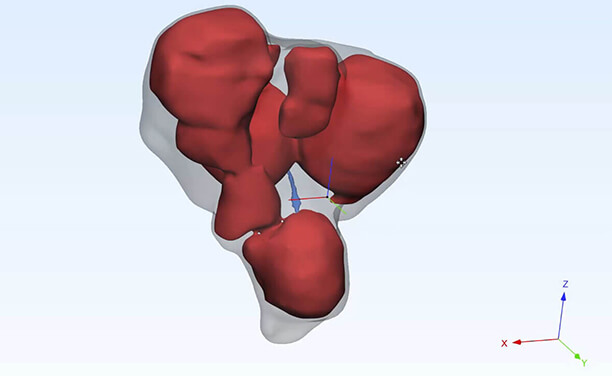

Dr. Teresa Flaxman, Research Associate at The Ottawa Hospital, said it was difficult to see tumours in the patient’s uterus on an MRI. So, she contacted the hospital’s 3D Printing Lab. She had heard how 3D-printed models were helping orthopaedic surgeons see exactly what they were operating on, so they could better plan the surgery.

In 2016, thanks to a donor’s generosity, The Ottawa Hospital acquired a medical 3D printer that uses acrylics and plastics to create exact replicas of patients’ bones and organs from a CT scan or MRI. With the opening of the 3D Printing Lab in February 2017, the hospital became the first in Canada to have an integrated medical 3D-printing program for pre-surgical planning and education.

Dr. Adnan Sheikh, Director of The Ottawa Hospital’s 3D Printing Program, said the Department of Orthopaedics is one of the main users of the lab, which prints models for orthopaedic oncology surgeons to plan operations in advance, reducing surgery times and costs.

“3D printing is revolutionizing the way we look at anatomy,” said Orthopaedic Surgeon and Oncologist Dr. Joel Werier, who has used 3D-printed models of his patients’ hips and bones since the lab opened. “It adds another perspective to how we view tumours, how we plan our surgery techniques, and our ability to offer precision surgery.”

Bones are relatively easy to create from CT scans and MRIs, said Dr. Flaxman. However, soft tissues, such as uterine tissue, is harder to identify, and a model hadn’t been made of one before.

“We’re going to be one of the first hospitals internationally to study how we can provide this improved care by using 3D-printed models in planning surgery for women’s health.”

Dr. Flaxman and other researchers from the Women’s Health Centre worked with Waleed Althobaity and Olivier Miguel at the 3D Printing Lab to create 3D images from an MRI of Maureen’s uterus. Then the lab printed a model that allowed them to see exactly where the fibroids and the lining of the uterus were located.

“This was a very challenging case,” said Dr. Sheikh. “The multiple fibroids within the uterine cavity made it very difficult to print, and we had to identify each one of them, in order to replicate the exact anatomy on a 3D-printed model. We used a softer, flexible material to create the model that was more consistent with uterine tissue.”

The model took 14 hours to print. Although the model was scaled to eight times smaller than her actual uterus, her fibroid-filled uterus was 20 times bigger than normal. Having a 3D-printed model was a huge asset to the gynecological surgery team, which included surgeons Drs. Singh and Innie Chen.

“This model helped to provide a good visual aspect. To have a model in my hands during surgery was incredible,” said Dr. Singh. “At the same time, we also had 3D images that I could look at on a TV screen in the operating room. It seems very futuristic, but in the operating room I was able to turn the image of the uterus at any angle or degree that I wanted, so I could see it from different perspectives, which helped during surgery.”

A picture might be worth a thousand words, but a 3D version is worth a million words. The 3D-printed models are not only helping surgeons, but also helping patients like Maureen understand their illness and prepare for their surgery. For patients, seeing a 3D model of the problem inside their bodies makes it tangible and real.

“Just before my surgery, Dr. Singh brought the model to me,” said Maureen. “He explained how he could use it in the surgery to see where the fibroids are, and he asked my permission to use it during the operation.”

She agreed, knowing that it would help other women suffering similar experiences. Dr. Singh successfully removed the fibroids, sparing Maureen from having a hysterectomy.

“We wanted to save her uterus in hopes that she can carry a pregnancy in the future, which wasn’t a hope for her up until this point,” said Dr. Singh.

“By working together with the 3D Printing Lab at The Ottawa Hospital, we’re going to be one of the first hospitals internationally to study how we can provide this improved care by using 3D-printed models in planning surgery for women’s health,” said Dr. Flaxman.

Dr. Sheikh said that, since the success of this first use of a 3D-printed model for gynecological surgery, the 3D Printing Lab is already working on a couple of other similar projects with the Minimally Invasive Gynecology team to offer other women alternatives to major surgery in the future.

Maureen was so grateful the gynecology team was able to spare her uterus, that she donated to the Gratitude Award Program to thank them.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.