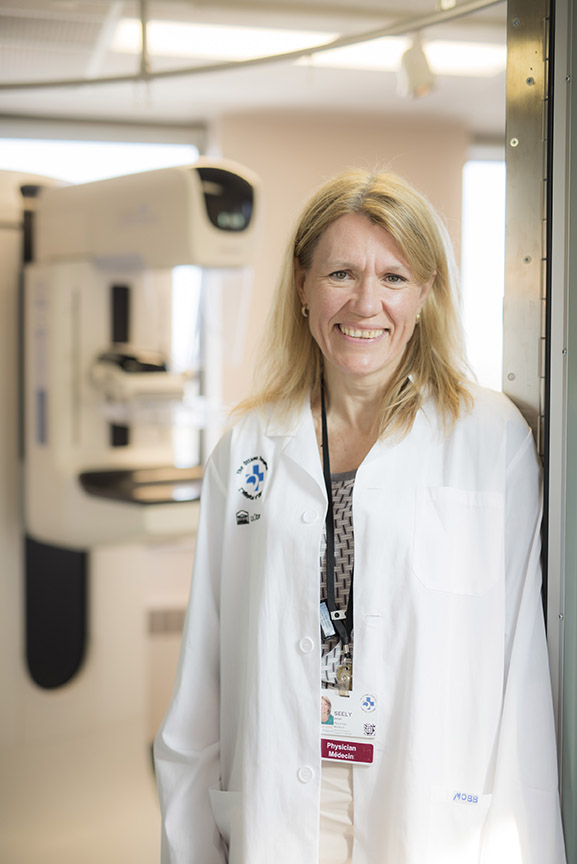

As the most common cancer, it’s no surprise there’s a lot of awareness around breast cancer. But there might not be as much awareness around the spectacular researchers and physicians who are changing the way we diagnose and treat breast cancer every day. The Ottawa Hospital is proud to say one of the most renowned of them works right here. Dr. Jean Seely is Head of the Breast Imaging Section at the hospital and a Clinical Investigator in our Clinical Epidemiology Program. Dr. Seely’s career is built on bringing research directly into patient care to improve the outcomes and reduce the mortality of breast cancer patients through better screening and diagnosis.

Read on to find out what Sci Fi innovation and personal family moment inspired Dr. Seely to become a breast radiologist.

Q: Did you always know you wanted to be a doctor — and specifically a breast radiologist?

A: I grew up in a family of doctors, so I was interested in being a doctor since I was five. My mother was a family doctor, and my father was a kidney specialist and worked in palliative care. My grandfather was a researcher and a doctor, and he always said medicine was the best field to go into — you could travel the world, teach, research, treat patients.

I knew I wanted to go into medicine, but I didn’t know much about radiology. After I completed med school in Montreal at McGill University, I did a general internship in Vancouver and realized how much I love to diagnose with my own eyes — to make early diagnoses. I remember watching Star Trek where they would use these machines to make diagnoses, and I thought that was something I wanted to do. [Editor’s note: those machines are tricorders.]

My grandmother died of breast cancer when I was four. She was diagnosed at 40, and it metastasized at 60. She would take care of me a lot, so I was very close with her. Looking back, she was instrumental in me going into breast radiology.

Q: How has the field of breast radiology changed since you started?

A: It’s dramatic! When I was in medical school in the ’80s, it’s when the old Canadian National Breast Screening Study was just being done. Nobody was really talking about screening before that; they didn’t pay attention to the quality of the mammogram. You’d get surgery to get a lump removed, and they’d diagnose it as cancer — or not.

“Not only can AI help with risk prediction, but it can improve the accuracy of the read of mammograms by 20%.”

— Dr. Jean Seely

What we do now is a mammogram and an ultrasound. We do a biopsy to see whether you have cancer, and you only get surgery once you have a proven diagnosis of breast cancer.

We have all these tools now that allow us to see cancer before it’s felt. In the ’90s, we started using MRIs for breast cancer, which is basically the most sensitive test for breast cancer. We now use ultrasound to screen — and to guide the needle for the biopsy.

We even have AI, and we can use the imaging components, pixels that are below the threshold of our eye, to predict whether someone will get breast cancer or not. Not only can AI help with risk prediction, but it can improve the accuracy of the read of mammograms by 20%. Some people say AI will take over the radiologist’s job, but I’m not at all worried about that. We do a lot of patient-centred care. We talk to patients, do biopsies, scanning — a lot of hands-on care on with patients.

Q: You’re leading the Tomosynthesis Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST) and recently reached 2,000 participants. Can you tell us a little more about this?

A: TMIST is a multi-centre trial, happening at hospitals around the world. We’re looking to recruit 160,000 patients, and we’re at 100,000. At The Ottawa Hospital, we have 2,000 of those patients.

It’s a randomized controlled trial, so patients go into one of two arms: one is the regular screening for breast cancer using a 2D mammogram, and the second is 3D tomosynthesis, which uses a different technology.

Tomosynthesis isn’t a true 3D image, because it doesn’t go all the way around the breast, but it’s a pseudo-3D, where using a very low radiation dose, we get a sweep of images. With 2D imaging, sometimes the compression of the breast creates an overlap of tissue that makes something look like a mass or a density of tissue hiding a cancer. The 3D technique has been shown to reduce the number abnormal recalls — where patients don’t wind up having cancer — and increase the cancer detection rate by 40%. It’s a win-win, where you have fewer abnormals that are truly normal and you have more abnormals that are truly abnormal cancers.

Some people might say, “Why are you studying it if you know it’s so much better?” But we haven’t studied it in a randomized control trial in a very large population. We’re looking to see if it reduces the rate of advanced breast cancers after eight years and if a broad range of people will benefit.

Q: What is The Ottawa Hospital doing in radiology and breast health that is exciting or groundbreaking?

A: What I love about The Ottawa Hospital is that there’s always been this attitude of being the best and trying for excellence — of trying things out and working together to make things happen. And it’s not always necessarily led by physicians — it’s very much a joint relationship between administrators and physicians.

I’ve been here since 2001, and when I’ve gone to meetings or elsewhere, I realize this isn’t the norm. This kind of collaborative approach for innovation and excellence is something we should be very proud of.

Specifically, we’ve implemented things like improving how we locate tumours that were found in screening. It sounds barbaric now, but we used to insert a wire in the patient’s breast on the day of their surgery, and it would be hanging out of the breast, and they’d use the wire to locate the tumour for removal. But now, instead of the wire, we use a tiny little “seed,” almost the size of a grain of rice, with a tiny amount of radiation. The surgeon uses a Geiger counter to find it. It saves money, reduces delays, and improves patient satisfaction — it really revolutionized the approach. We were the third site in Canada to implement this.

We’ve also reduced the amount of time it takes to get an MRI. We used to screen women at higher risk, or those with dense breast tissue, for 45 minutes. We shortened it to 12 minutes. There’s been a huge improvement in patient satisfaction, outcomes, and capacity. Research helped provide this benefit. We were also one of the first in Canada to do this.

Q: If someone has just been diagnosed with breast cancer, what advice would you give them or how would you respond to them?

A: The key when I talk to patients is that there is always hope.

I think the whole reason why it’s important to do this is to undo some of the fear of the diagnosis of breast cancer. One in eight women will get breast cancer. Nobody wants to deal with it, but it’s something we have to be aware of. We have these great tools and wonderful people who are committed to diagnosing and treating it. That’s my hope with this, to provide encouragement.

Unfortunately, there are some people where they present really late, and when they get diagnosed, it’s already spread. That’s harder for us to deal with. That’s one of the reasons I do so much research — because I’m always trying to reduce that advanced cancer rate.

The key in these cases is compassion. My father was a palliative care physician and he always said he learned the most about living through dealing with the dying.

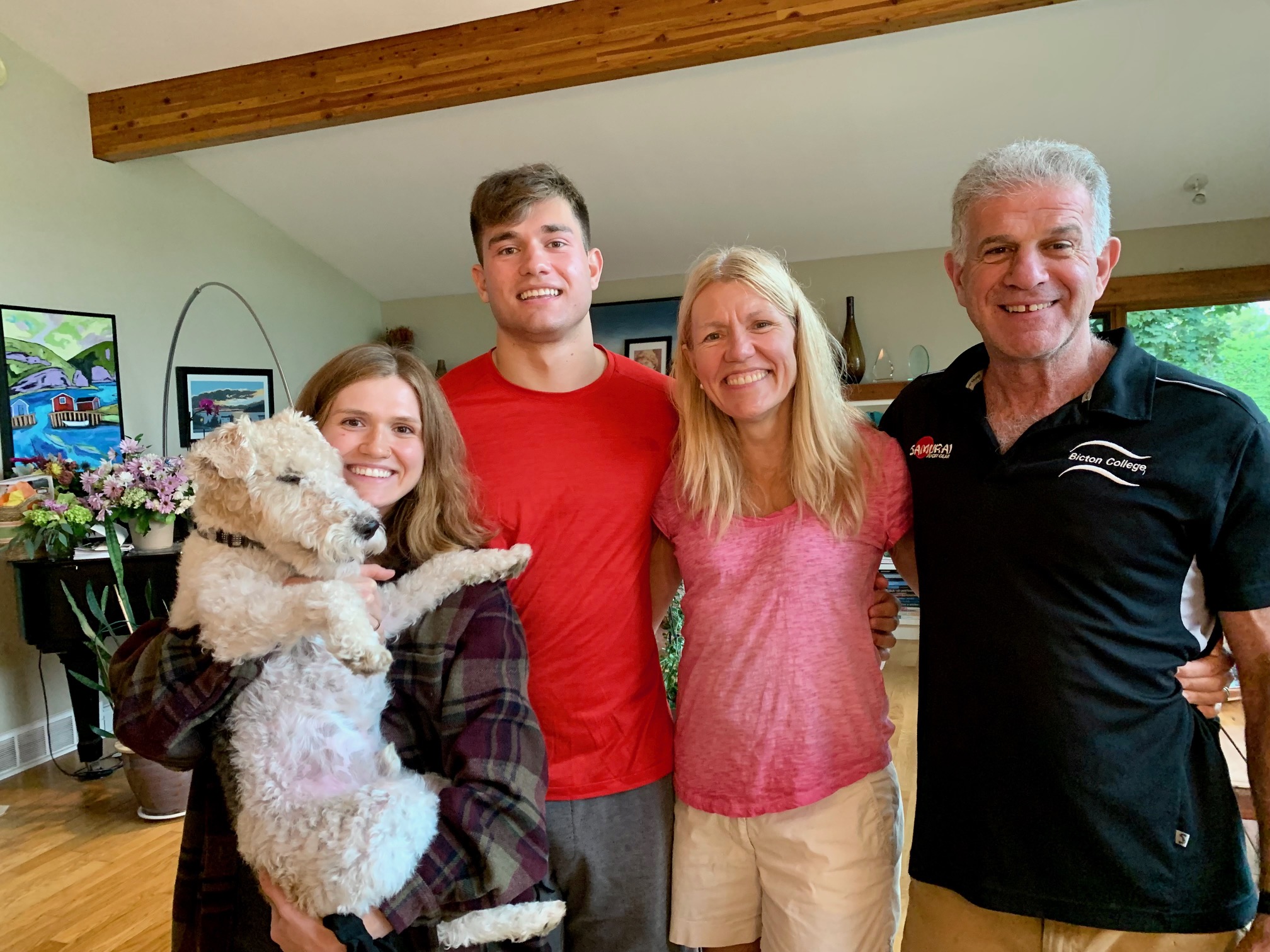

Q: What would we find you doing when you aren’t at the hospital

A: I get a lot of inspiration from my two children and my wonderful husband and friends as well as my three siblings. You might find me in the Gatineaus riding a bike. I also love to ski — cross-country or downhill. I get a lot of benefit from doing exercise in the outdoors. I also love to read — anything with good storytelling — one day I’ll write a book.