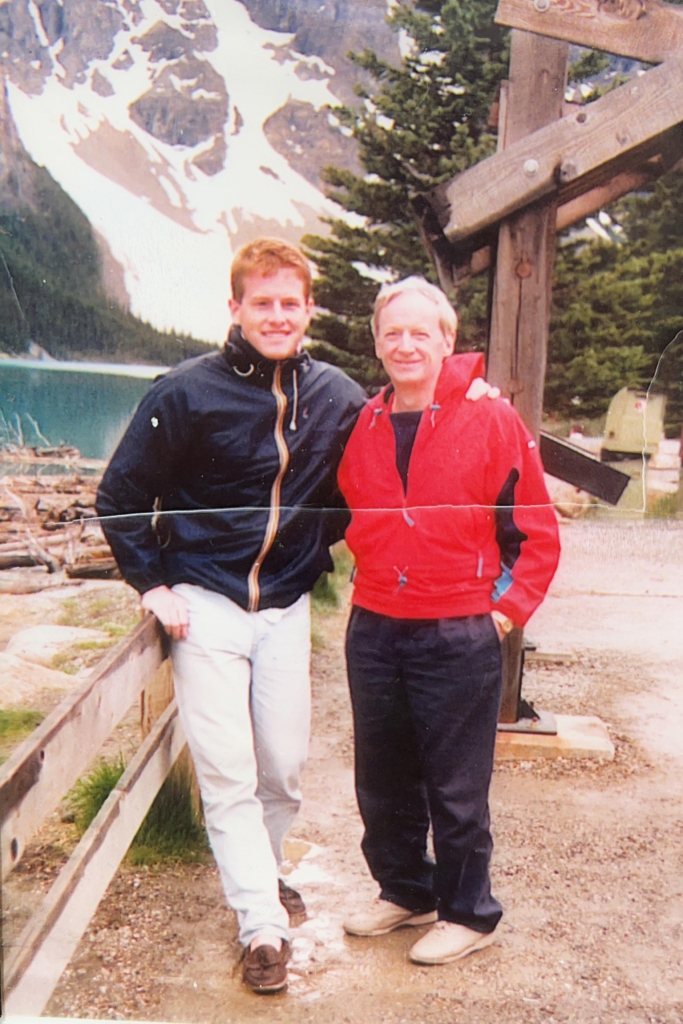

Like father, like son, the saying goes. But Dr. David Grimes was dead set on making his own way in the world of medicine.

Son of the much-admired neurologist, Dr. J. David Grimes, he never thought he’d wind up in the same field, let alone studying the same exact disease, as his father — but life had other plans.

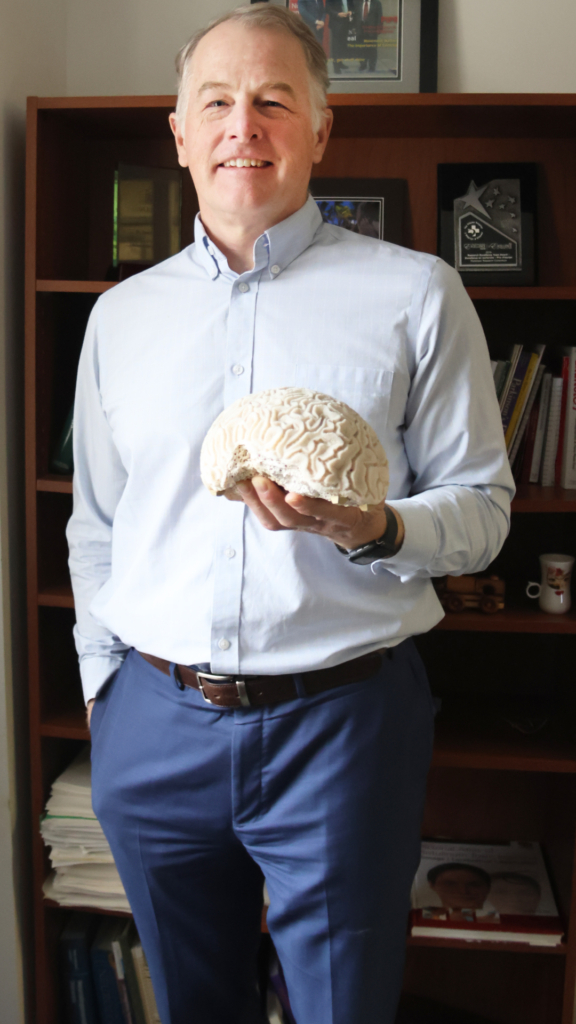

Now a Neurologist and Associate Scientist at The Ottawa Hospital, and Director of the clinic that his father founded — the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Clinic — Dr. Grimes is leading a new generation of researchers as they take on Parkinson’s and treating some of the very same patients his father did.

Find out how Dr. Grimes got pulled into the field of neurology and what advice he has for people diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

Q: What were your early years like?

A: I was born in Cleveland, Ohio, but I grew up in Ottawa’s west end.

I went to Sir Robert Borden High School, where I struggled at English but the sciences were up my alley. My wife always teases me that I almost failed Grade 13 English then went on to write two books and over 100 research publications. But back then, I was a science guy and a gym rat. I played every sport available through grade school and got into football in high school.

Family was very important growing up. I was one of six siblings, and every Sunday was family day; you had to be around. My father would arrange various nonsense games or tennis tournaments, and there were enough kids that we’d have our own teams. I’m the second born, and my older sister was my boss. It’s a family joke that she got into hospital administration when I got into medicine.

Q: How did you decide to study medicine?

A: I knew I wanted to be a doctor quite early on. My grandfather was a dermatologist, and my father was Dr. J. David Grimes, founder of the Ottawa Parkinson’s Disease Research Laboratory at what was then the Ottawa Civic Hospital. I admired them both.

I also started working at the Civic as a porter when I was 16 and stayed until second year medical school. Back then, many sections of the hospital weren’t air conditioned, and we’d have big buckets of ice with fans blowing on them all summer.

While I knew I wanted to be a doctor, there was this cliché of following in your father’s footsteps, and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to branch out on my own, so I started in internal medicine and studied at the University of Ottawa.

Q: How did you wind up in neurology and specializing in Parkinson’s?

A: The problem is, my father and I tended to have pretty similar personalities. I was helping him with his research and early books while I was doing internal medicine, and after a couple of years, I realized I did like neurology. But I said I wouldn’t pursue movement disorders specifically like he did. Lo and behold, I did like movement disorders. I liked caring for patients with Parkinson’s, and it was the patient population that gave me the most joy to work with.

What drew me to neurology was our lack of understanding of the brain. There was a classic knock against neurologists when I started that they can diagnose things but can’t treat anything. It was apparent to me that there were a lot of things we could treat, and there seemed to be a very bright future. This was back in the ’90s, and we had started to see people who had potentially devastating strokes, and now they were surviving. There were more and more opportunities to look after people and make a difference in their lives.

Q: How has the treatment for Parkinson’s changed since you started?

A: Levodopa has been the gold standard for treating Parkinson’s since the 1960s, and it does make a remarkable difference, but we understand the drug a lot better than we used to. We’re more careful about dosing and spacing and we can add on other medications.

Did you know? Levodopa was made famous partially by the 1990 movie Awakenings, in which Robin Williams plays a neurologist using the drug to treat catatonic patients.

Just this year, Health Canada approved a way to give levodopa under the skin, and we were one of the first centres in Canada to use this drug. We also offer DUODOPA, which is levodopa infused right into the stomach. Because we’re a subspecialized clinic, we can offer things like this really early.

We also have more advanced therapy options, like deep-brain stimulation. We’re one of the few places in Canada that offers it. The idea is that by putting electrodes in the brain, you can change the abnormal loops that are associated with Parkinson’s and help people move better again.

Q: What’s something surprising about your field?

A: It’s very complicated and expensive to get new drugs to market. We’re about to embark on a new clinical study for which we got a very large donation, but it’s amazing how quickly you go through the money. I don’t know if everyone understands how complex the process is.

We’ve been very fortunate to have our Parkinson Research Consortium. Through it, we’ve been able to raise many millions through local donations, and we’ve been able to recruit new people, fund six basic science students, and support clinical programs with that money. Local donations are absolutely crucial to start a new project and get things going.

Q: In your role as a scientist, what research are you currently working on?

A: We are currently working on a 40-person trial trying drug repurposing. We’re using a rheumatoid arthritis drug called Plaquenil, which can affect certain inflammatory pathways that we think play a role in people with Parkinson’s.

I’m also looking at the role of MRI scans in diagnosing Parkinson’s. We helped develop a software that uses an AI algorithm to look at standard MRI scans and can, with good accuracy and sensitivity, tell you whether you have regular Parkinson’s or something else.

We also have studies looking at genetic subtypes of Parkinson’s, and we are part of the Parkinson Study Group, which is the most prominent Parkinson’s clinical trial group in the world.

We have a very large and active clinical trial program here at The Ottawa Hospital. When we approach someone and say, “We’ve got something new we want to try,” they say, “Yeah, sign me up.” Even when we recently had one trial come back negative, the compound we tried wasn’t working, most people said, “OK, what do you have next for me?” This level of enthusiasm isn’t necessarily common in all patient populations.

From a patient engagement standpoint, our Parkinson’s patients are extremely engaged.

Q: Chantal Theriault came to us with early-onset Parkinson’s, what makes cases like hers unique?

A: The earlier somebody’s onset is, the more likely their Parkinson’s is to have a genetic basis. In general, people with a genetic cause tend to progress more slowly, but they also tend to have more trouble with motor function fluctuations. We think up to 10% of people with Parkinson’s have a genetic mutation causing it. We can test for these genetic mutations now, and with that knowledge, we are hoping to develop treatment to block the progression. Unfortunately, there’s not a lot now in the clinical realm, but in the research realm, it’s a very active area. It speaks to the idea of precision medicine and coming up with very specific treatments for people with very specific genetic forms of Parkinson’s.

Q: What advice would you give someone who has just been diagnosed with Parkinson’s?

A: In general, I tell people that although it does progress, and although we don’t have a cure, it does typically progress slowly. I encourage them to be active and enjoy life. We know exercise is a key part of treating Parkinson’s — it helps people feel better and function better.

It’s important to tie in significant others as well. Pulling support from a lot of different places is critical for patients to do the best they can and have the best overall quality of life.

I make sure they know there’s a lot of research going on, and we are going to be able to come up with treatments that affect the progression.

People have this vision that they’ll be in a wheelchair within a year of diagnosis and that’s just not true. We really do keep most people feeling and functioning quite well with Parkinson’s for many years and for some decades. I try to instil a feeling of hope.

Q: How will a new, state-of-the-art health and research centre to replace the aging Civic Campus mean for your patients?

A: A fluid back-and-forth between clinical research and patient care is being built into the new campus development. If we’re going to be a leading-edge hospital, we need to do that. When we see research patients and clinical patients in the same place, that’s where we’ll make our most rapid advancements.

From infrastructure for new technologies to connecting patients to new research, the new campus will make everything that much more accessible and advance the field that much faster.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not at work?

A: Most people who know me think of me as being on my bicycle. I bike all year round, and the residents make fun of me when I show up for work on a snowy day in my biking gear.

My wife and I also have three children, and we enjoy spending time with them. I play on their volleyball team, where I’m the old guy trying to keep up.

Otherwise, you’ll find me at my cottage where I have all the classic cottage projects on the go: building bunkies, docks, and various other things. It’s just 90 kilometres from my house, so I can bike to my cottage or commute from there in the summer.