When, if ever, is it acceptable to enrol patients into a clinical trial without their informed consent? How do we recruit patients into trials when seeking their consent could compromise the results?

These are the critical questions philosopher-bioethicist Dr. Cory Goldstein asks in his role as a Postdoctoral Fellow at The Ottawa Hospital and at the University of Ottawa (uOttawa). From developing ethics guidelines to improving the quality of research that ultimately benefits patients and healthcare providers, Dr. Goldstein is using his philosophical skills to ask and answer some of the most compelling and complex questions about healthcare research ethics.

Find out why the Grimshaw Researcher in Training Award winner despised philosophy in high school (but eventually came around), what he finds so fascinating about clinical trials, and where he recommends going for the best ramen in Ottawa.

Q: What were your early years like?

A: I grew up in Cambridge, Ontario, and as a kid, I loved puzzles. Every Friday, I’d go to my grandparent’s house for dinner, and they would cut out math problems from the newspapers. Sudokus, word jumbles, word searches… I loved them all.

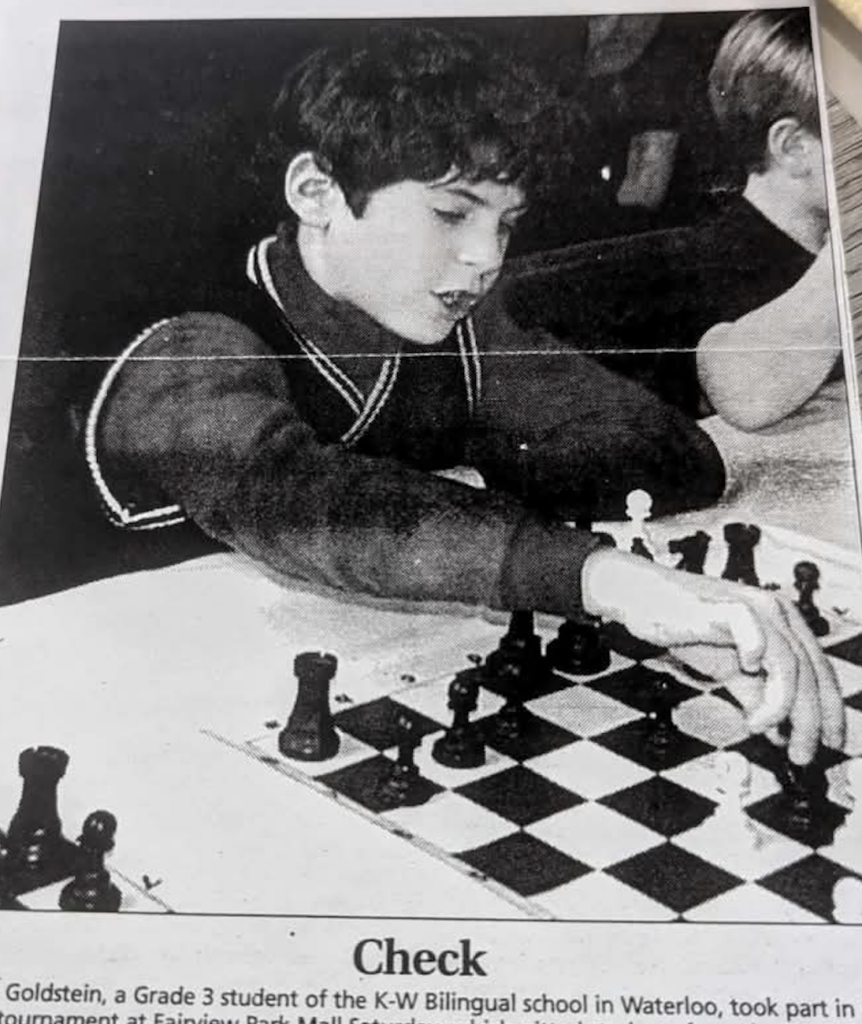

I also played a lot of chess, even playing competitively in a provincial tournament. I was enrolled in soccer, too, but I was one of the kids who’d duck and hide any time the ball came close to me — I preferred watching the dandelions grow and the clouds pass by. Later on, I’d get into playing sports recreationally, but at that time, eating oranges at halftime was the highlight of the game.

Q: How did you get into philosophy?

A: It was sort of an accident. Funny enough, in high school, I was enrolled in the International Baccalaureate program, and one of the required courses was a philosophy course called Theory of Knowledge. Students had to write a long essay to complete the course, so I dropped out of the program because I disliked writing assignments, and I wasn’t interested in philosophy.

My favourite subjects at that time were math and physics (because it was math-related). I definitely did not enjoy the sciences; I felt I was done with them after the compulsory Grade 10 science course.

Q: Do you have any favourite books?

A: Le Petit Prince and Oh, the Places You’ll Go, I keep going back to those books. They’re not just for children, you know!

When I started university at McGill in Montreal, for math, I also took anthropology, psychology, and a philosophy course. It turns out I actually really liked philosophy. Being inspired by professors at the undergraduate level really changed my opinion.

I think the reason I like philosophy is close to the reason I liked math to begin with: they both involve trying to solve complex problems and learning about how great thinkers did this. I ended up graduating with a major in philosophy and a minor in education.

Q: What drew you to healthcare?

A: After graduating, I knew I wanted to continue studying philosophy, but I also wanted to be in a more collaborative environment. Traditional philosophy can be very isolating. I kept asking myself, “Should I go to graduate school to study philosophy?”

I happened to find a professor, Dr. Charles Weijer at Western University. He was working on two projects at the time: one exploring ethical issues in neuroimaging after serious brain injury, the other exploring ethical issues raised by cluster randomized trials (a complex clinical trial design). When I was accepted to a one-year master’s program in philosophy at Western, he asked which project I was more interested in. I said clinical trials, and he said, “No one usually says that!” I guess philosophers tend to gravitate towards neuroethics, and questions like: What is consciousness? When should someone be considered dead? You know, the big questions. But the ethics of clinical trials just sounded more interesting to me!

I wound up doing an MA and a PhD in philosophy, focusing on research ethics. Specifically, I looked at issues with informed consent in pragmatic clinical trials. Most clinical trials test whether some new treatment will work in optimal, tightly controlled settings. However, pragmatic trials test whether existing healthcare treatments, practices, or policies work in messy and unpredictable clinical settings. These trials should be inclusive; they want to represent everyone. But asking people for their consent might lead to refusals, and if too many people refuse to participate, this undermines the goal of including everyone. In my PhD dissertation, I looked at how this tension could be resolved. I explored whether patients have an enforceable moral duty to participate in research (I argue no — they don’t), and whether the broad use of a waiver of consent can be used to facilitate this kind of research (I argue no — it shouldn’t).

My solution was asking a simple question: what is informed consent? Informed consent is about giving people the opportunity to make an intentional, informed, and voluntary decision about whether to participate in research. This doesn’t require a complicated 20-page form to sign. It could just be a brief conversation between the patient and their doctor about the study and, if the patient agrees, documenting their consent in their electronic health record. I argue this approach is both ethical and can facilitate the conduct of pragmatic trials.

“Over the last 10 years, Dr. Goldstein has demonstrated exceptional productivity and leadership in the ethics of randomized controlled trials. He is emerging as a leader of the next generation of research ethicists internationally.”

— Dr. Charles Weijer

Q: What are you currently researching?

A: My primary focus is to update international ethical guidelines for cluster randomized trials. In 2012, my PhD supervisor, post-doc supervisor Dr. Monica Taljaard, and a large interdisciplinary team published what’s called The Ottawa Statement on the Ethical Design and Conduct of Cluster Randomized Trials. It’s the first and remains the only international ethics guidance document specific to these trials. As I was finishing my PhD in 2022, I helped Charles and Monica secure a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to update these guidelines, and I moved to The Ottawa Hospital to help lead this work. We’re a team of over 30 people across four continents, including five patient and public partners helping us with the update.

I still write a lot about informed consent, too. But I also publish on other issues raised by complex clinical trial designs, such as those related to identifying research participants, assessing benefits and harms, protecting vulnerable participants, health equity, data sharing, and participant and community engagement.

Q: How does your research help patients?

“Without patients’ trust, important research cannot be done. I think my work helps patients by making sure that when they do participate in research, it’s research that’s held to a high ethical standard.”

— Dr. Cory Goldstein

Q: Do you have any unusual fears?

A: Lake sharks. I know there are no sharks in lakes, but there’s something in there.

A: By developing clear ethics guidelines for researchers and research ethics committees to follow, and therefore by making sure we do research in the right way, we preserve patients’ trust. Without patients’ trust, important research cannot be done. I think my work helps patients by making sure that when they do participate in research, it’s research that’s held to a high ethical standard.

Q: How does it feel to win this award?

A: I was blown away. Flabbergasted. When I found out I won this award, I was like, “Are you sure?” To receive this award is huge. I am truly honoured The Ottawa Hospital has embraced a philosopher like me.

Q: Who is your mentor?

A: I have three! Charles, my PhD supervisor, who’s just an incredible academic with demonstrable integrity. He taught me not just how to work with teams but how to build teams. He’s a natural leader, teacher, and collaborator. Of course, Monica, my post-doc supervisor. She is brilliant. Everything she does is meticulous and thoughtful. She also cares deeply about the students she supervises. And then my wife, Magdalena. She exudes compassion, patience, and empathy — qualities I truly admire.

“Cory stands out among his peers not only in terms of his unique expertise, but also in terms of his exceptional writing and communication skills, adaptability, and high-quality contributions to both ethics and methodology-oriented projects. He has certainly been one of the most outstanding post-doctoral fellows I have encountered in my career at the OHRI.”

— Dr. Monica Taljaard

Q: What’s something your colleagues don’t know about you?

A: I have aphantasia. I always thought when people said “picture something in your mind’s eye” they were speaking figuratively. Turns out, people can see things when they close their eyes! Not me.

Q: What’s something your family might not know about your job?

A: They don’t understand what I do. I tell my parents I published an article, and they ask how much I got paid, and I have to say, “No, no, I paid $3,000 to publish it!” They know that I love what I do, and that’s all that really matters.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not at work?

A: I have good boundaries with my work, so I keep it nine-to-five, Monday to Friday. When not at work, I’m with my daughter. My daughter is my everything. We go to the beach often; she’s an avid swimmer at just 16 months. Since she was born, she’s loved water. I also exchanged my front door for one of those revolving doors because we have friends and family visiting constantly. We also love exploring our community and eating at local restaurants. Right now, our favourites are Ng’s Cuisine, Authentic Vietnamese Pho House, and Farinella Pizza. I also think I have eaten at all the ramen places in Ottawa: Ramen Isshin is the best by far.