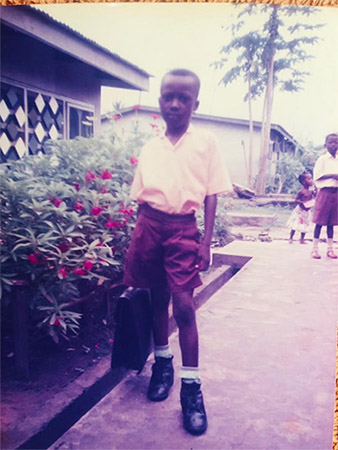

Dr. Meshach Asare-Werehene has come a long way to get to where he is today. Literally — moving from Ghana to the U.K. and then Canada as well as spending some time in Japan. It came as no surprise to Dr. Asare-Werehene’s parents that their son would pursue medical research; as a young boy, he carried around a briefcase instead of a backpack (earning him the nickname “headmaster” — he just didn’t like how backpacks jumbled his books and papers) and asked for insects and lasers instead of toys and dolls. He was known for asking his teachers so many questions they thought he was mocking them and for refusing to go to library sessions with his class until they got more science books.

Today, Dr. Asare-Werehene — an expert in gynaecological cancer diagnosis and therapeutics, a part-time academic staff at the Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences at the University of Ottawa, and Cancer Program Lead at the Tsang Laboratory, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI) — is still asking questions. Recently, he received the Worton Researcher in Training Award for his cutting-edge discoveries, extraordinary leadership, and for one of the answers he found during his PhD. He discovered chemo-resistant ovarian cancer cells produce large amounts of a protein called plasma gelsolin, which prevents cancer-killing immune cells from doing their job. This finding could help improve both the detection and treatment of ovarian cancers.

When Dr. Asare-Werehene isn’t busy with his work, he can often be found enjoying nature with his family. His wife, Dr. Afrakoma Afriyie-Asante, is also a brilliant cancer and infectious disease immunologist, and they welcomed their first son in August 2021. He describes cooking as his therapy, whipping up international dishes with a Ghanaian spin, and he finds fellowship at his church, keeping Philippians 4:13 (New King James Version), in mind throughout it all: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

Read on to learn more about Dr. Asare-Werehene and what drives his passion for changing the course of cancer diagnosis and treatment in Canada and beyond.

Q: Is there a specific moment you can pinpoint that made you decide to pursue medicine?

A: Growing up in Ghana, I never took no for an answer. When I was seven, I heard a conversation going on between my parents and one of our uncles, and I heard my uncle say that our auntie died of cancer because there was no treatment for her. I was like, “Why is there no treatment? Is it a money issue? Or did we have to transfer the drug from one clinic to the other?” My parents nearly punished me for interrupting a senior discussion; in Ghana you don’t interrupt high-level conversation. But my uncle calmed them down and said, “All the treatments weren’t working for your auntie, so there was nothing that could help her.”

I never knew that could happen. What my uncle said ignited my passion. Since then, I made a promise to myself that I was going to pursue this; I was going to help patients like that get better, and I was going to understand why some patients don’t respond to chemo.

Q: Why did you move from Ghana to the U.K, then to Ottawa? And what was that like?”

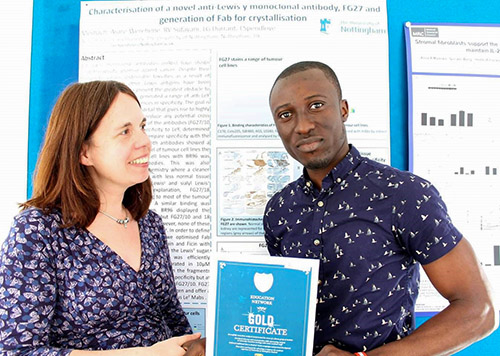

A: I was fortunate because I graduated from my undergraduate in Ghana with a first-class ranking (I was one of only two), and I was the second best in my class. Interestingly, my wife (then my classmate) was the best and the valedictorian for the entire college of health sciences! We both had a similar type of scholarship to go to the University of Nottingham in the U.K. I pursued cancer immunology, and it was there I got exposed to the various dimensions of investigating cancer. When I graduated from that program, I was the best in my program and received the gold certificate for my outstanding academic and leadership performances — my wife was studying microbiology and immunology and emerged as one of the best in her program. I got to know about The Ottawa Hospital and how they integrated research into patient care, and the immigration policies here were more favourable to me. In Canada, I could stay longer after I finished schooling to pursue opportunities. Professionally, it was the best decision I ever made.

Personally, it’s been tough, because I left my family behind to pursue my career interests. Also, until I left Ghana, I didn’t know I was Black. It was when I began to travel that I experienced racism, from being policed around high-end shops to being discredited for my own work to being asked to go back to my own country.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your discovery and what receiving the Worton Researcher-in-Training Award means to you?

A: For the past 30 years, the survival rate for ovarian cancer has not gotten that much better, compared to other cancers. It’s still around 45%, which means when a patient is diagnosed today, the probability of living to see the next five years is 45%, which is super low. And this is mainly due to late diagnosis as well as the fact that most patients do not respond to the conventional treatments. So, to find a reason why patients could be resistant to treatment, as well as finding ways to energize their immune system, was exciting and fulfilling. This will be like your immune cells being taken to the gym so they become powerful and kill the cancer cells. My curiosity in life has always been to find the problem, so this is what I’ve always dreamt about.

“The award tells me the hospital and entire community has confidence in my work. It inspires me to continually push the boundaries and develop excellent international research.”

— Dr. Meshach Asare-Werehene

The award tells me the hospital and entire community has confidence in my work. It inspires me to continually push the boundaries and develop excellent international research. I’m also the fifteenth recipient and the first Black person, for me this is huge. It’s difficult to become something when there’s no one to look up to. I’m excited that generations coming after me will see the path created and can say “Meshach was there hence we can also be there”; this is not only for me, but also for my family, my mentors, and so the Black community has someone to look up to.

Q: What do you see for the future of The Ottawa Hospital?

A: I think the future is super bright for The Ottawa Hospital. I look forward to it becoming a world leader in patient care and groundbreaking research, and a world-leading centre in training the next generation of clinicians and researchers and allied health professionals. With the New Campus Development being built, there will be a major boost to all of this. I will also look forward to seeing more diversity at every level involved in patient care, decision making, research discoveries, as well as management. This I see happening in the next few years, so I’m super confident.

Q: What’s next for you personally and professionally?

A: I look for advancing my clinical and research careers to the stage where my findings will be translated into the clinic to give patients a second chance, to have more time with their families. And personally, I look forward to having more quality time to spend with my family, especially my son. Also, I’d like to finish my second book and pick up a new skill, like sewing or advancing my cooking skills. Finally, I’m interested in politics, so I hope to translate my studies onto the political scene to benefit my whole community.

“I’m excited that generations coming after me will see the path created and can say ‘Meshach was there hence we can also be there’; this is not only for me, but also for my family, my mentors, and so the Black community has someone to look up to.”

— Dr. Meshach Asare-Werehene

In this four-part series, Dr. Asare-Werehene discusses what drives his research, his hopes for the future of cancer treatment, and the importance of representation in the research and medical field.