Growing up in Austria, Dr. Michael Schlossmacher couldn’t have foreseen his future as a physician-scientist conducting groundbreaking Parkinson’s research at The Ottawa Hospital. His career started with medical school in Vienna, followed by graduate studies in human biology. By the late 1980s, he found himself in Boston pursuing post-doctoral work on Alzheimer’s disease. In 2006, The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI) recruited Dr. Schlossmacher to their team, and he opened a new laboratory as a member of the Parkinson’s Research Consortium Ottawa early the following year. His work is dedicated to improving the lives of individuals with neurodegenerative diseases.

Keep reading to learn how he got to where he is today and about the role philanthropic support has played in his research.

Q: What were your interests as a child?

A: As a young child, my favourite thing was sharpening pencil crayons of different colours. I thought maybe I’d be a pencil sharpener later in life. I also loved building things, LEGO trucks and miniature train sets. In middle school and high school, my weakest subjects were biology and English. My focus between the ages of 10 to 18 were soccer and track and field, but when I sustained a significant knee injury, I became interested in anatomy and how to repair things. From a very young age, I was interested in how things went awry.

Q: How did you decide to study medicine, biology and later, neuroscience?

A: I don’t remember the precise decision making. I just knew I was fascinated with the notion of health and disease. It was more like a gut feeling. My parallel interest was art, so in the beginning, I pursued both medicine and art school. I wound up doing a combination of anatomy instruction, drawing, and studies

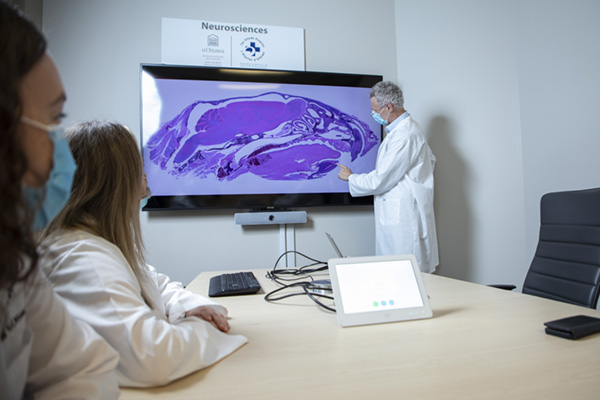

My fascination with biology really took off when I started pathology — learning in a more structured manner what all the diseases of the body were, and how organ disfunction evolves into disease.

After medical school, I decided to go through more structured scientific training and moved to Boston, Massachusetts on a Fulbright scholarship at Harvard University. After I met my wife, I took on a job as a research assistant in an Alzheimer’s research lab because I ran out of money, thus learning on the job.

Q: What are the most promising Parkinson’s discoveries happening right now?

A: The first one, and it’s not yet mainstream, is to see that Parkinson’s is similar to other diseases that occur later in life, whereby multiple factors have to work together: there’s a genetic component; there’s a series of environmental factors; there’s the sex effect, males are more affected; and then there is this progression in risk with every year we live longer. It’s true for every other disease whether it’s breast cancer or coronary disease, that these factors all work together. We have to think more holistically.

Number two is that inflammation is very important. We now know that people with chronic inflammation from hepatitis B, hepatitis C, inflammatory bowel disease (such as Crohn’s disease), or skin conditions like rosacea — all these conditions increase, measurably, the risk for Parkinson’s disease. Chronic inflammation, wherever it sits in the body, seems to promote the development of Parkinson’s.

Q: How is donor support important for your research?

A: Philanthropic support is critical in particular in the early phases of research. It helps us develop results that can be used to effectively raise money from other sources. We once looked at how much money we raised through our Parkinson’s Research Consortium, and every dollar raised through philanthropy leveraged $10 to $15 from federal and foundation sources. We are so grateful for these gifts!

It also allows our research initiatives to explore ideas outside of the mainstream — to challenge dogmas, to shake the tree, to rattle your colleagues with new concepts. Philanthropic support has allowed us to make several important discoveries here in Ottawa that have influenced the field.

Philanthropy has the potential to transform research activities in a lab by amplifying the energy and invigorating scientists; plus, supporting talented trainees fuels their drive to develop creative ideas.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.