The care of premature babies has changed a great deal since the first incubator was introduced in 1880 or the first neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) opened in 1960s. At no other time in history has the future for premature babies been so bright. Between 2004 and 2017 alone, the survival rate of preterm babies in Canada increased by 25% thanks to new and improved practices. But, there are still challenges and risks when infants are born pre-term.

There are about 29,000 preterm babies born in Canada each year.

In Canada, 8% of births are preterm.

TOH delivered 5,931 babies last year.

25%

Between 2004 and 2017, the survival rate of preterm babies increased by 25%.

When is a baby premature?

A typical pregnancy is 40 weeks, and any baby born before 37 weeks is considered premature. In Canada, approximately 8% of all births are premature.

There are three subcategories used to describe how premature babies are:

Infants born before 28 weeks are often called “micro-preemies,” and these account for only 2% of all premature births. Usually, the earlier or smaller the baby is, the more at-risk for health issues they are.

What is BPD?

One of these issues is bronchopulmonary dysplasia — or BPD — which is a chronic lung disease that most often occurs in premature or low-weight babies who have received supplemental oxygen or received mechanical ventilation for long periods.

Dysplasia refers to any abnormal development of cells, and in the case of BPD, these cells are located in the smaller airways and lung alveoli (the small air sacs in the deep lung where oxygen is taken up and waste carbon dioxide exhaled). Damage to these parts of the immature lung makes breathing difficult and can cause issues with lung function.

This abnormal cell development is now known to be a response to damage or trauma of the lungs and airways of babies before or soon after birth. This damage and trauma can be due to administering oxygen, using mechanical ventilation, pneumonia, or infections.

First described in 1967, BPD is the most common complication in extreme prematurity infants, occurring in around 35% of these cases.

How is BPD diagnosed?

A diagnosis of BPD is made using a combination of: identifying characteristic symptoms and risk factors, x-rays, blood tests, and echocardiograms. Some of the signs and symptoms of BPD include: rapid and/or shallow breathing, shortness of breath, chronic coughing, flared nostrils when breathing, bluish skin due to low oxygen, or noises like grunting or wheezing when breathing.

What is the treatment for BPD?

The majority of BPD cases will resolve on their own as the baby grows, although babies with BPD may be at higher risk of asthma, viral pneumonia, or respiratory infections as they grow up. In a few rare cases, there are serious complications including high blood pressure in the lungs, called pulmonary hypertension.

The main treatment for BPD today centres around prevention, developing ventilation technology that causes less damage to infants’ delicate lungs, as well as keeping them on ventilators or supplemental oxygen for as short a period as possible.

Premature babies often need extra oxygen and mechanical intervention to breathe, but this can damage their lungs, causing a chronic lung disease.

A stem cell treatment that may help heal the lungs of premature babies is currently in clinical trials at The Ottawa Hospital. Read more.

One major cause of BPD is that premature infants don’t produce enough surfactant — a substance that reduces the tension of pulmonary fluids in the lungs — and so they may receive surfactant-replacement therapy. Giving the pregnant parent steroid treatment before birth is also shown to help reduce the risk of BPD in preterm infants.

Medications like bronchodilators (to widen the airways), diuretics (to reduce the amount of water in the body), antibiotics (to control infections and pneumonia), and steroids (intermittently, and to reduce inflammation) may be used in babies with BPD.

What is the future of BPD?

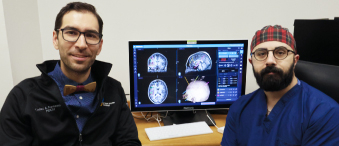

There has been an increase in BPD cases over the past few decades, but that is likely due to the increased survival rates of preterm babies in general. Fortunately, there is promising research into BPD happening right here at The Ottawa Hospital. Dr. Bernard Thébaud is leading a clinical trial to test the feasibility and safety of using stem cells to treat premature babies with BPD, and his team is building a “cell atlas” to show how cellular changes happen during the last phases of lung development. These innovations could have real treatment implications for babies with BPD in Ottawa and beyond.

There were 535 admissions to the NICU last year.

260

of those admissions were preterm.

We currently receive 1,300 admissions a year between our 24-bed Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for extremely premature infants at the General Campus and our 17-bed Special Care Nursery for moderately premature infants at the Civic Campus. Community support for the hospital means their parents — and the babies themselves — are receiving the best care possible, creating tomorrows for our very youngest patients.