Published: January 2024

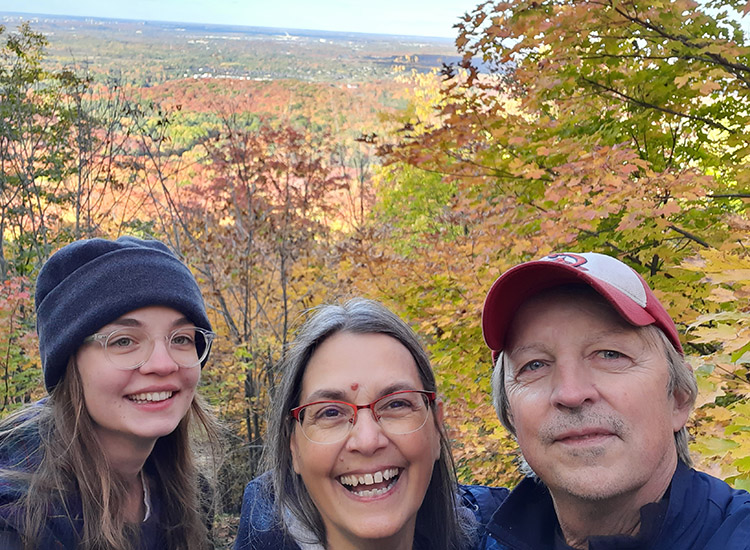

When Sean Heron attended Nipissing University in North Bay, he was in his element. This avid hiker enjoyed the area’s countless hiking trails and being outdoors. However, he also started to notice a shift in his mental health. That shift would eventually bring him back home to Ottawa and lead him to The Ottawa Hospital’s mental health team and a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

It was during Sean’s first year in North Bay that he started to have mental health challenges, including intrusive thoughts, diet and sleep disruptions, and waning trust in others. He realized something was wrong and took the initiative to get checked at a local hospital, where he was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. But Sean wasn’t convinced by this assessment. “I did my research, and I realized that what I had was nothing close to what those conditions were described as. But I kind of left it at that and just continued with my life,” explains Sean.

When things didn’t improve, he left school and North Bay and returned home to his parents’ house. He got a job in the grocery industry, but in 2021, he started to hear voices at home and at work. “One day when I was at work, I asked a colleague if they heard the same thing, because I couldn’t believe that I was hearing these things,” says Sean. “It was kind of concerning.”

Sean’s parents were more than a little concerned. “I could always see it in their faces that they were so worried — it was hard on my parents,” remembers Sean. “There were times where I lashed out. I started yelling at them because in my head, I had this delusion that they were part of this — part of the reason why I was feeling this way. I never talked to them like that before, so it was out of character for sure.”

Sean described the voices as high pitched. “It didn’t sound like human voices. It was like a dog whistle sort of thing. I would hear full sentences.”

Discovering the hospital’s On Track: First Episode Psychosis Program

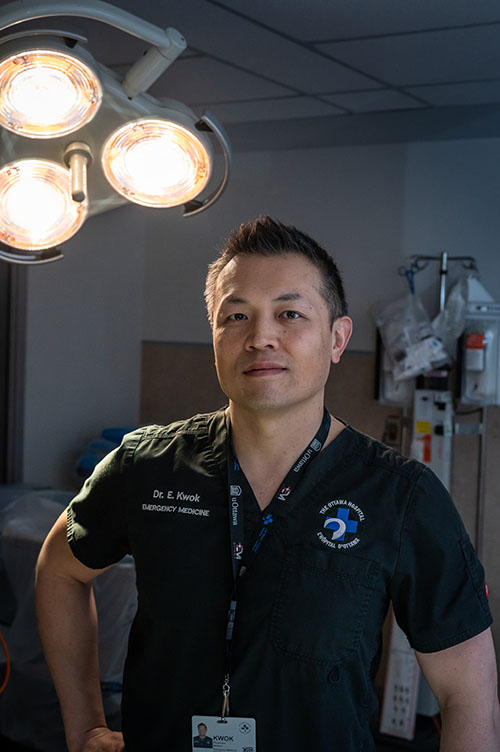

Concern over what was happening eventually brought him to The Ottawa Hospital’s Emergency Department at the Civic Campus. Our mental health program provides early diagnosis and treatment of severe mental illness. With two psychiatric emergency services and 96 acute inpatient beds, our hospital is the largest provider in the region for acute mental health care and often the first place those experiencing a mental health crisis in our city will turn to for help. When Sean arrived, he was introduced to On Track: The Champlain First Episode Psychosis Program.

"Something important to recognize about schizophrenia is one of the first things that happens is people lose the ability to recognize there is something going wrong."

— Dr. Sarah Brandigampola

Read our Q&A with Dr. Brandigampola

Dr. Sarah Brandigampola, a psychiatrist at The Ottawa Hospital, recalls when she first met Sean. “He was very ill. He was lucky to have parents who knew something was going on and were trying to get him some kind of help — there were safety concerns — but up to that point he was told he wasn’t right for certain clinics,” explains Dr. Brandigampola. “So, by the time we met, Sean had been sick for at least a year, if not longer.”

It was February 2022 when Sean was diagnosed with schizophrenia — he had what’s described as auditory hallucinations, according to Dr. Brandigampola. “The experience of hearing people speak to you, even when you’re alone — it’s very distressing. Something important to recognize about schizophrenia is one of the first things that happens is people lose the ability to recognize there is something going wrong.”

This is known as a neurological phenomenon called anosognosia. “When people have anosognosia, it doesn’t matter how much you tell them the voices aren’t real or you’re not being followed, they can’t comprehend that,” explains Dr. Brandigampola.

It turns out, Sean’s early symptoms began when he was in North Bay. His first symptoms were very similar to depression, he couldn’t focus and started losing motivation to go to school and going out with friends. Dr. Brandigampola says this is very typical for the early stages of schizophrenia — people start to isolate themselves and lose interest in things. That can go on for months or years before the voices or delusions begin. It’s at that point, many people turn to drugs or alcohol to help alleviate that pain. That’s exactly what happened in Sean’s case.

Almost a sense of relief with diagnosis of schizophrenia

The diagnosis brought almost a sense of relief to Sean. “It was like this validation — that you’re not alone. It is a known condition and there was help available, so really, it was a relief.”

"It was like this validation — that you're not alone. It is a known condition and there was help available, so really, it was a relief.”

— Sean Heron

Now that Sean was enrolled in the On Track program, he had a full team of professionals ready to help him. As Dr. Brandigampola explains, it’s a recovery focused program. Remission is a step in the process to eliminate the symptoms, but recovery is the goal — to get the patient’s life back on track in terms of school, work, relationships, and hobbies. “We want them living a life that has meaning to them and where they’re pursuing their goals.”

The first step in the treatment is a medication to help quiet the voices. This can take some time to achieve, but Sean responded well. Things significantly improved when he went from oral medication to a monthly injection — it’s long-acting and patients don’t run the risk of forgetting to take a pill daily.

Once he began medication, the next step was to work on the basic structure of his day, because Sean had been spending all of his time alone. That’s where his recreational therapist came into the picture. Patients like Sean are introduced to a variety of interest groups to help them reintegrate into social settings. There are groups for walking, sports, education, and a general recreation group. “Sean was interested in those groups, and that was a way for us to get him out of the house,” according to Dr. Brandigampola.

Full team assembled to assist

Another member of Sean’s team included a neuropsychologist, who did cognitive assessments. This helped prepare Sean for a goal that was very important to him — returning to school.

Incredibly, in September 2022 — only seven months after his diagnosis — Sean enrolled as a part-time student at Carleton University majoring in psychology. “Given just how sick he had been and how he had been isolated for a long time, the groups helped get Sean active again and helped motivate him to ask himself, ‘What else do I want?’” explains Dr. Brandigampola.

Occupational therapists also helped set Sean up for success. “Melissa was my occupational therapist and she helped me get to where I needed to be to start school. She helped me set up appointments with academic advisors to see what kind of credits I needed to continue with. She even helped me pick my courses,” says Sean.

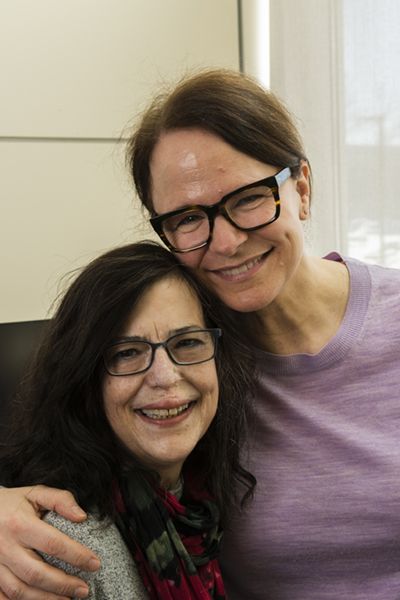

The team is also made up of 10 primary clinicians — five registered nurses and five social workers. Maeve Blake, a social worker, was one of Sean’s clinicians in his first 18 months of the program. Her role was to oversee, counsel, and support patients like Sean throughout the program. “The primary clinician works closely with the patient and their family if they’re open to that. We can provide psychoeducation about schizophrenia, what recovery can look like, how clients can promote their own recovery, and what helps in terms of lifestyle changes, social supports, substance use — all those kinds of things,” explains Maeve.

How to set patients up for success?

Small goals are set for the patient to help put them on a path for success. “A big piece of the work that I did with Sean early on was behavourial activation. We worked on activity schedules and addressed how his substance use at the time was getting in the way of his recovery and his goals,” explains Maeve.

“Sean wanted to go back to school and finish his degree, so that’s what we worked on. At On Track, we focus on what’s important to the client,” says Maeve. “It’s not about us imposing goals on them but about getting to know them as individuals — help me understand your life and what’s important to you.”

There are common themes within patients, but it’s very much a uniquely tailored approach based on each patient’s needs, according to Maeve.

The first year of the program focuses on getting people well and stable, while the second year is about setting goals and helping the patient work towards them. Then by the third and final year, the care team can start to take a step back with a goal of transitioning the patient back to their family doctor.

This specialized program has worked incredibly well for Sean, who is currently in his second year of the program. Maeve says he’s always been internally driven to get better, and she admits that’s not always the case with some patients. “What was lovely to see as Sean’s symptoms became better controlled was how warm and genuine he is. Watching his true personality re-emerge was wonderful and uplifting.”

"This is a young man who got his life back. It’s a family that got their son back. It shows that these types of interventions work.”

— Maeve Blake

“I don't know where I would be without this program.”

Today, Sean is 25 and continuing his studies part-time. He still loves playing video games and in the warmer months, you’ll find him biking and hiking — he loves the outdoors. He also continues with the On Track program — a program he’s truly grateful for. “It’s like a gift really. I don’t know where I would be without this program.”

"This is world-class care, and this is what I would want for everybody — certainly my loved ones.”

— Dr. Sarah Brandigampola

Dr. Brandigampola is quick to point out that the program does take self-referrals, so if people have concerns about themselves or someone they care about, they can always call the On Track program and arrange a consult.

For Sean, treatment will be lifelong, but as he gets older, Dr. Brandigampola is hopeful new research advancements — including advancements made at The Ottawa Hospital — will provide patients like him more options.

But for now, this program is an important steppingstone. “This is a critical program for patients with schizophrenia. This is world-class care, and this is what I would want for everybody — certainly my loved ones.”