Published: July 2024

Imagine a constant whooshing sound, like a washing machine, in your ear day in and day out — 24 hours a day; never a peaceful moment — even when you’re trying to sleep. For millions of people worldwide, the cause is something known as pulsatile tinnitus. Now, in a world first, The Ottawa Hospital has discovered a potential cure for the majority who live with this debilitating condition.

Chris Scharff-Cole had lived with pulsatile tinnitus for years, but like many, she didn’t know what was wrong and was constantly searching for help. The now-retired psychotherapist from Deep River, two hours west of Ottawa, spent 30 years helping others using her horses as a part of her therapy practice. As a long-time horse person, Chris has seen her share of injuries over the years — including multiple joint replacements. While she’s learned to live with chronic pain, it was that constant sound coming from her right ear that left her wondering how she would ever find peace again.

It wasn’t until she met Dr. Robert Fahed, Interventional Neuroradiologist and Stroke Neurologist at The Ottawa Hospital, that she finally found relief.

Brain aneurysm brings patient to the Civic’s Emergency Department

In 2021, Chris was suffering significant pain, so her doctor sent her to Pembroke for an MRI. That scan showed a brain aneurysm, and she was transported by ambulance to the Civic Campus’s Emergency Department. “I had extreme head pain. When I was asked to describe it between 1-10, I said it was 13,” explains Chris.

While waiting with paramedics in the Emergency Department, a top surgeon came down to see her. That was her first introduction to Dr. Fahed. “He listened to the side of my head, and he knew what to do. He said, ‘It’s ok, we’re getting things ready for you.’ It was so busy, but he was truly compassionate.”

“There was a throbbing in my head 24 hours a day that sounded like a washing machine. The pumping in my right ear was constant. It distorted my ability to hear, but mostly, I couldn’t sleep."

— Chris Scharff-Cole

Dr. Fahed and his team performed surgery on the aneurysm, and it was a success, but during regular follow-up, Dr. Fahed uncovered an underlying problem impacting Chris’ quality of life.

Chris had pulsatile tinnitus. “There was a throbbing in my head 24 hours a day that sounded like a washing machine. The pumping in my right ear was constant. It distorted my ability to hear, but mostly, I couldn’t sleep. Even when I fell into a sleep from exhaustion it would wake me up.”

“She had been suffering for years, but when Christine complained to her doctors, she had been told there’s nothing wrong with her ears — multiple scans said everything is normal,” says Dr. Fahed.

He adds it was actually an underlying vessel condition that was the real culprit, one that not many ENT specialists or radiologists know to look for on scans. “This vessel is close to your ear. It’s disrupting blood flow and that’s generating waves. It’s because your ears are fine that you’re able to hear that abnormal flow disruption.”

“No one else in Canada is caring for those patients.”

— Dr. Robert Fahed

What is pulsatile tinnitus?

It’s estimated that 750 million people around the world are affected by some form of tinnitus, and Dr. Fahed says 10 to 20% of those patients have pulsatile tinnitus. Unlike the more common forms, they don’t usually hear a ringing sound, but rather they hear a whooshing sound, like a heartbeat sound constantly in their ear. “Ninety percent of these patients with a pulsatile tinnitus have an underlying curable vascular cause. Among the possible techniques/devices that can be used is the technique we have pioneered with Christine,” explains Dr. Fahed.

The challenge is most people live with this problem because they’re not able to find a solution — much like Chris. But a team at The Ottawa Hospital is giving hope to those suffering. “What’s tough with this is there are vey few people around the world who know how to manage those patients, do the proper work, find a cause, and treat them,” explains Dr. Fahed.

That is why in late 2023, The Ottawa Hospital’s Pulsatile Tinnitus Clinic was launched. The only other clinic is in Toronto. “No one else in Canada is caring for those patients,” says Dr. Fahed.

It was Chris’s case that inspired this leading interventional neuroradiologist, one of only four in Canada, to focus more of his time on this area of medicine.

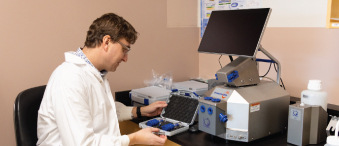

Pioneering a new treatment for pulsatile tinnitus

In March 2023, Chris was the first patient to undergo a new technique pioneered at The Ottawa Hospital. There are various reasons for pulsatile tinnitus, and the cause for Chris’ was a venous diverticulum, which is a rare defect that consists of an outpouching in the wall of a venous sinus, a vein that carries blood from the brain.

This new technique is called Intrasaccular Flow Disruption. According to Dr. Fahed, it consists of putting a small sphere of metal inside the vein pouch. The sphere traps the blood inside the diverticulum, then creates a clot and the blood will no longer enter that vein. “It’s the blood flow inside that outpouching that is creating waves that are heard by the ear, because of its proximity to the ear.”

"It’s minimally invasive surgery, we go through the groin, we fix whatever anomaly we find, and we cure your pulsatile tinnitus."

— Dr. Robert Fahed

Unlike other techniques used, this one doesn’t require a stent. There are no blood thinners required and the patient requires no medication afterwards.

“The patient comes in for a day procedure. It’s minimally invasive surgery, we go through the groin, we fix whatever anomaly we find, and we cure your pulsatile tinnitus. When you wake up from the procedure the sound is gone. You’re home the same day. It’s incredible,” says Dr. Fahed.

That day when Chris woke up from the procedure, her life changed completely. “When I opened my eyes I said, ‘It’s gone.’ I had total trust in Dr. Fahed. He is gifted. Life is peaceful. I appreciate each day that I’m not haunted by that sound. Every day I wake up is a blessing.”

Not settling for the status quo

She was glad to go first and now hopes it will help others in the future. “We’re absolutely blessed to have access to this type of care. I’m glad to be a recipient, and I hope more people will have this procedure. I’m so grateful and we do what we can to support the hospital – I’m so glad we have Dr. Fahed at The Ottawa Hospital,” shares Chris.

“The Ottawa Hospital pioneered this new technique — we thought outside the box to make it happen.”

– Dr. Robert Fahed

Referrals can be faxed to

613-761-5360

Dr. Robert Fahed

- Ottawa Pulsatile Tinnitus Clinic.

As of July 2024, Dr. Fahed and his team have treated 17 patients for this form of pulsatile tinnitus. It’s important to know that the technique can be used to treat other cerebrovascular conditions and patients are welcome to reach out to the Pulsatile Tinnitus Clinic to learn more.

“It’s another example of how TOH is at the forefront of innovative care,” says Dr. Fahed. “The Ottawa Hospital pioneered this new technique — we thought outside the box to make it happen.”

Dr. Fahed adds this is just the beginning. It’s the launch of a new area of care.