Published: April 2025

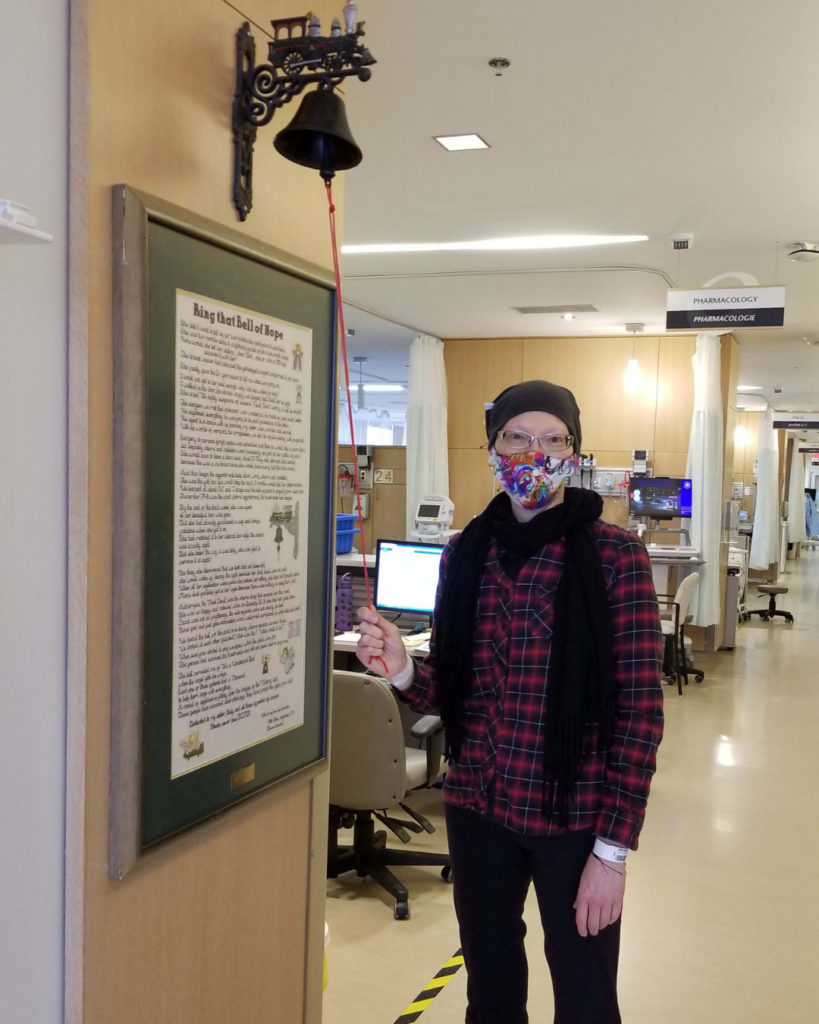

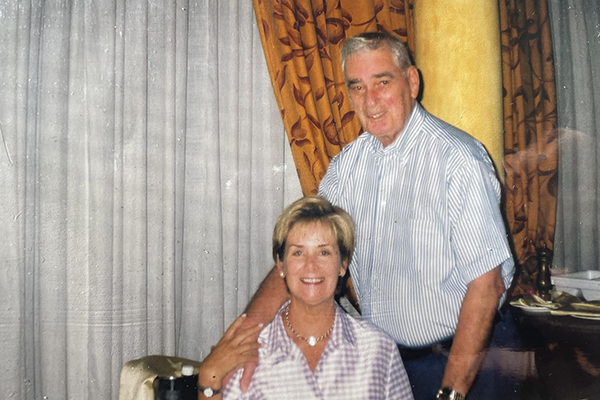

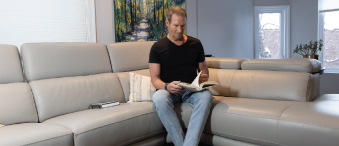

Three times a week, you’ll likely find Chantal Theriault kickboxing to stay in shape — physically and mentally. It’s a sport she picked up easily from her father, Jean-Yves “The Iceman” Theriault — a world kickboxing champion. It’s the strength she developed from this sport, along with her sense of humour, that helped her navigate through an astonishing medical diagnosis five years ago. At the age of 37, Chantal learned she had early-onset Parkinson’s disease — this was one hit she didn’t see coming.

The distressing news for this otherwise healthy young woman was delivered during the peak of the pandemic in the summer of 2020. Initially, there were many more questions than answers. Still, never one to back down from a challenge, no matter how insurmountable this one appeared to be, Chantal came to terms with the news, educated herself, and put her trust in the committed physicians and researchers at The Ottawa Hospital (TOH).

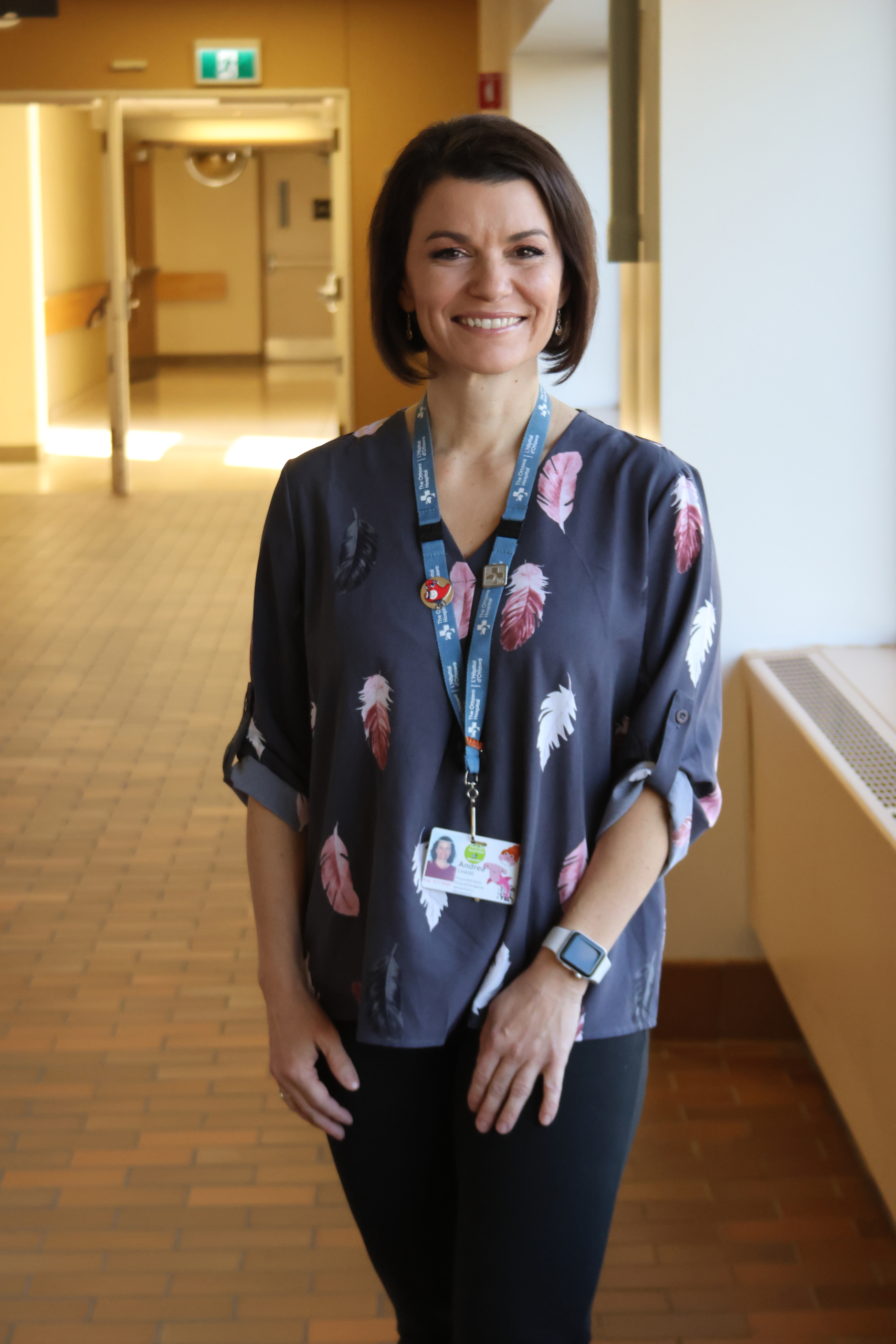

Chantal is all too familiar with our hospital but from a different vantage point. She’s a program coordinator in the Critical Care Department. She’s been a part of the TOH family for 22 years — she started in Admitting Services and worked her way to where she is today on the Intensive Care Unit team. It’s a team for which she has the utmost respect, and she plays an important role.

“Any resident that must do their rotation in the ICU comes through me. I do the scheduling for the Civic and the General campuses. There are about 300 residents that come through the year,” explains Chantal.

Working in the ICU for so many years, she has garnered the utmost respect from her colleagues for the high quality of her work and her pleasant demeanour.

It started with tremors in her hand

As Chantal was busy with her work, during the height of the pandemic, she developed a tremor in her arm. “It started in my hand and then made its way up my arm, and eventually I could feel it in my leg a little bit. I initially thought I pinched a nerve in my neck.”

“When I walked, he noticed that my right arm didn’t swing. That was a big sign. After a few other tests, I learned I had early-onset Parkinson’s.”

— Chantal Theriault

As an avid kickboxer, she exercises regularly and has dealt with a minor injury or ache in the past. She was going to try her chiropractor, but she kept putting it off and eventually, it was recommended she might want to see her family physician, as the symptoms progressed.

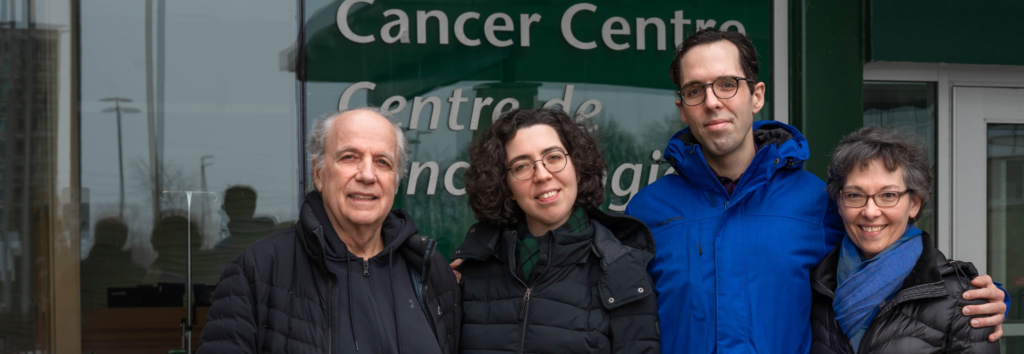

Photo credit: Ashley Fraser/Postmedia

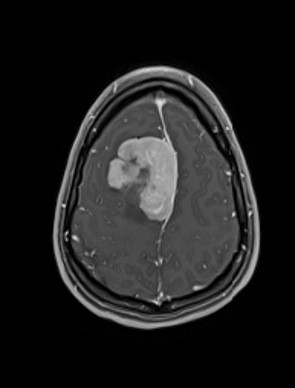

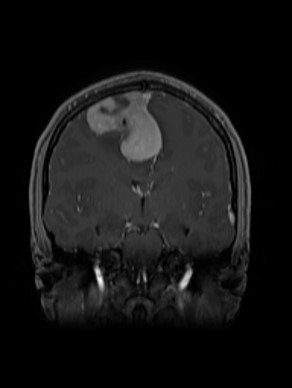

After several tests, including an MRI, which showed nothing concerning, she met with a neurologist at The Ottawa Hospital, who put Chantal through several physical tests. “When I walked, he noticed that my right arm didn’t swing. That was a big sign. After a few other tests, I learned I had early-onset Parkinson’s.”

At that point, Chantal’s mind just completely shut down, as she describes it. “The two people that I think of right away when I hear Parkinson’s are Michael J. Fox and Muhammad Ali. I wondered, ‘What the hell do I have in common with these people?’”

What is Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinson’s disease is a movement disorder that affects the nervous system. The symptoms start slowly but progress over time, and although tremor is a common symptom, slowness and stiffness are additional features present early on. The risk of Parkinson’s increases with age, and men are more likely to develop it than women. When a person is diagnosed before the age of 40, it’s often referred to as early-onset Parkinson’s.

That day of her diagnosis, Chantal went home and had what she describes as a moment of woe, and then she moved on — grateful to work at The Ottawa Hospital and to be surrounded by some of the best care team members in the world.

“There will be mobility issues someday but that's down the road. Right now, I have things to do. I have a life to live.”

— Chantal Theriault

“I don’t know what this means or what the progression timeline looks, but I’ve got a team behind me — I’ve got this. There will be mobility issues someday but that’s down the road. Right now, I have things to do. I have a life to live.”

All about Parkinson's

She also used humour to help get through some of those early days of living with Parkinson’s, including a new tattoo that she got done on the inside of her right arm. It reads, ‘Shaken not stirred’.

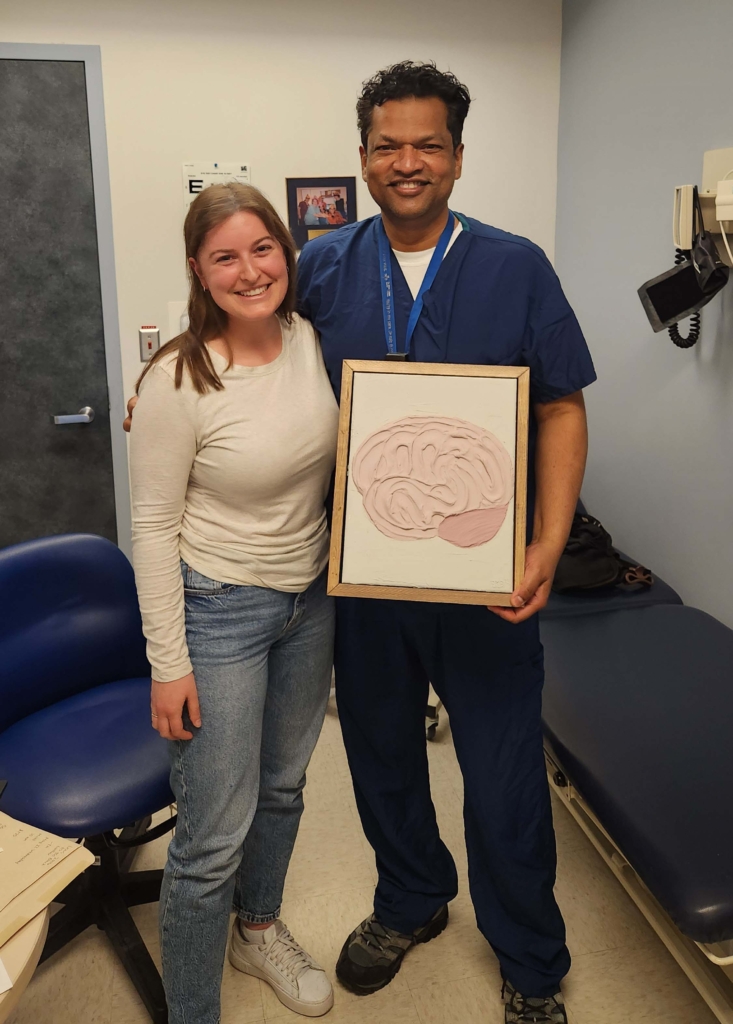

Another big step in this new journey for Chantal was meeting Dr. Michael Schlossmacher, Director of the Neuroscience Program at our hospital. “He is the most incredible human being — super supportive, super down to Earth,” says Chantal. “He takes the time, and he encouraged me to bring a family member during my follow-ups if they have questions.”

That’s also around the time where the impact of research came into play for this young woman. She’s enrolled in two research projects at our hospital, including one Dr. Schlossmacher is leading.

The global impact of Parkinson’s research

It’s research that drives Chantal. She’s put all her efforts into helping to advance treatment options and hopefully to help scientists find a cure for the disease someday. That’s what motivated her to create the Kick It for Parkinson’s fundraiser, which supported The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research — an organization that has funded research here at The Ottawa Hospital.

In December 2024, an international team led by Dr. Schlossmacher received a US$6 million grant from the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) initiative, in partnership with The Michael J. Fox Foundation, to continue their work on reduced sense of smell in Parkinson’s disease — a testament to our leadership in research.

“Our interdisciplinary team is on the leading edge of this topic, making discoveries that could one day impact diagnosis, prevention, and possibly, patient care.”

— Dr. Michael Schlossmacher

“Understanding the loss in sense of smell in Parkinson’s is having its moment right now,” says Dr. Schlossmacher. “Our interdisciplinary team is on the leading edge of this topic, making discoveries that could one day impact diagnosis, prevention, and possibly, patient care.”

More recently in another study, the first clinical trial of its kind showed interpersonal psychotherapy may be better than other types of psychotherapy for treating depression in patients living with Parkinson’s. People with Parkinson’s often experience depression, but there’s been little research to show what type of psychotherapy works best.

The trial, led by Dr. David Grimes, Director of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Clinic and Dr. Diana Koszycki at the University of Ottawa, assigned 63 people with Parkinson’s and depression to one of two types of psychotherapy for 12 sessions. The group with interpersonal psychotherapy had significantly lower depression scores.

Director of the Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Clinic

“Psychotherapy is an important option for treating depression in Parkinson’s. Healthcare providers should consider recommending it alone or in combination with antidepressants,” says Dr. Grimes.

It’s patients like Chantal that make this type of research possible. “I’m very proud to have the opportunity to be part of the studies I’m involved in. This was a life-changing diagnosis, and if taking part in these studies is what’s going to make a difference, then I’m going keep doing it,” she says.

Dr. Schlossmacher adds that working with patients is a privilege and calls their courage and commitment “humbling”. He refers to Chantal as a source of inspiration and motivation for him and his research team.

Building a new neuroscience centre

The new neuroscience centre, to be located at the new hospital campus on Carling Avenue at Preston Street, will have the potential to be among the best in the world. It will combine cutting-edge research with clinical treatments to accelerate the development of new therapies for conditions such as Parkinson’s, stroke, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and more to help patients just like Chantal.

"“There's going be a cure for Parkinson's, maybe not in my lifetime but there will be. I hope that I get to see it and then I can say, I was part of that study.”

— Chantal Theriault

As the research continues to move forward, Chantal will be more than a spectator as she continues to help advance scientific discoveries through her participation and fundraising whenever she can.

As her tremors are controlled today by medication, she’s proud to be a part of the TOH family that’s working towards progress. “There’s going be a cure for Parkinson’s, maybe not in my lifetime but there will be. I hope that I get to see it and then I can say, I was part of that study, or when Dr. Schlossmacher gets the Nobel Prize or something, I can say I know him.”

As she takes a moment to pause, tears fill her eyes, then Chantal continues. “It makes me proud. It makes me very proud to work for this organization.”