Published: May 2025

The Ottawa Hospital is creating a comprehensive epilepsy program — a one-stop shop, if you will — that will have a huge impact on patients. As a complement to this specialized care, the hospital completed its first-ever stereoelectroencephalography (stereo EEG) procedure on January 13, 2025. This minimally invasive surgery identifies the precise areas in the brain where seizures originate and provides care teams with detailed information to develop more targeted and effective treatment plans for those with epilepsy.

Previously, patients from our region needed to travel to Southern Ontario for this type of procedure. Now, care can be delivered closer to home, saving patients time, money, and allowing them to stay close to family.

“We’ve all seen it on TV or in the movies.”

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder, and a seizure is a sudden burst of electrical activity in the brain that causes a temporary disturbance in the way brain cells communicate with each other. The kind of seizure a person has depends on which part and how much of the brain is affected by the electrical disturbance.

A seizure may take many different forms, including a blank stare, uncontrolled movements, altered awareness, odd sensations, such as smelling something that’s not actually there, or convulsions.

Dr. Tadeu Fantaneanu, the Medical Director of the Epilepsy Program in our EEG laboratory, explains the latter is known as tonic-clonic seizure, previously called a grand mal seizure. “That’s when the person falls to the ground, foams at the mouth, and shakes. We’ve all seen it on TV or in movies.”

Our program serves approximately 13,000 people living with epilepsy in our region. We also have what’s called a transfer and transition clinic with CHEO. “Those are patients who have had epilepsies since they were quite young, potentially since birth or later on in their childhood years or adolescent years, and they get referred to us when it comes time to transfer into adult care,” he says.

According to Dr. Fantaneanu, epilepsy can affect anyone at any age, but there are two peaks — prior to age six and over 65. In young patients, it’s usually because of genetics, and in older patients, it’s often because of the damage that a brain will accumulate over a lifetime.

Building a comprehensive epilepsy program

In the last five years, our hospital’s Epilepsy Program has grown tremendously, thanks to a partnership with the Ministry of Health and a $12-million grant, as well as donations from the community. As Dr. Fantaneanu explains, the goal of the grant is for The Ottawa Hospital to become a regional epilepsy surgery centre. That’s a provincial designation and it will ensure that we will have the ability to perform high-level surgeries that are not currently available in this region.

Dr. Fantaneanu says this is something patients in Eastern Ontario desperately need. “They could have their tests and care done here, but eventually, if surgery was needed, they would be a referred to a hospital in Toronto or London — as many as seven to eight hours away.”

Travel that takes time, money, and patients away from their loved ones and careers. “Patients would have to be away from their families at a vulnerable time in their lives, when they’re admitted in the hospital, potentially after a brain surgery,” he adds.

Over the course of the past several years, Dr. Fantaneanu and his team have built up testing capabilities for patients and the monitoring unit continues to grow. It’s where the team evaluates patients who have seizures. It’s currently a four-bed unit and at the new hospital campus it will be a six-bed unit — all private rooms.

Attracting the best and the brightest in epilepsy care

It was the impressive plans to build a comprehensive epilepsy centre that attracted Dr. Alan Chalil to our hospital in 2024, to become the Surgical Director of the Epilepsy Program. He is a neurosurgeon with training focused mainly on epilepsy and surgical treatment of epilepsy — that includes implantation of stereo EEG. He completed his training in London, home of the largest surgical epilepsy centre in Canada, and Emory University in Atlanta.

“It was a very unique opportunity because it seemed like bringing in my training would be the last piece of the puzzle to fit into that whole picture in terms of how to treat epilepsy,” says Dr. Chalil. “Coming to a new team that’s being developed was a nice opportunity and also a big challenge.”

“Epilepsy surgery is about finding that delicate balance: freeing the patient from seizures while preserving the brain’s normal function. That’s why it means so much to me."

— Dr. Alan Chalil

As he explains, while epilepsy surgery has been practiced for over 80 years, the transition to stereo EEG in North America continues to highlight many unknowns. “Epilepsy doesn’t have to define a person’s life, but its unpredictable nature can still disrupt it in profound ways. Seizures can interfere with everything — work, relationships, social life, even financial stability,” explains Dr. Chalil. “Epilepsy surgery is about finding that delicate balance: freeing the patient from seizures while preserving the brain’s normal function. That’s why it means so much to me.”

Meet neurosurgeon Dr. Alan Chalil

The first stereo EEG at The Ottawa Hospital

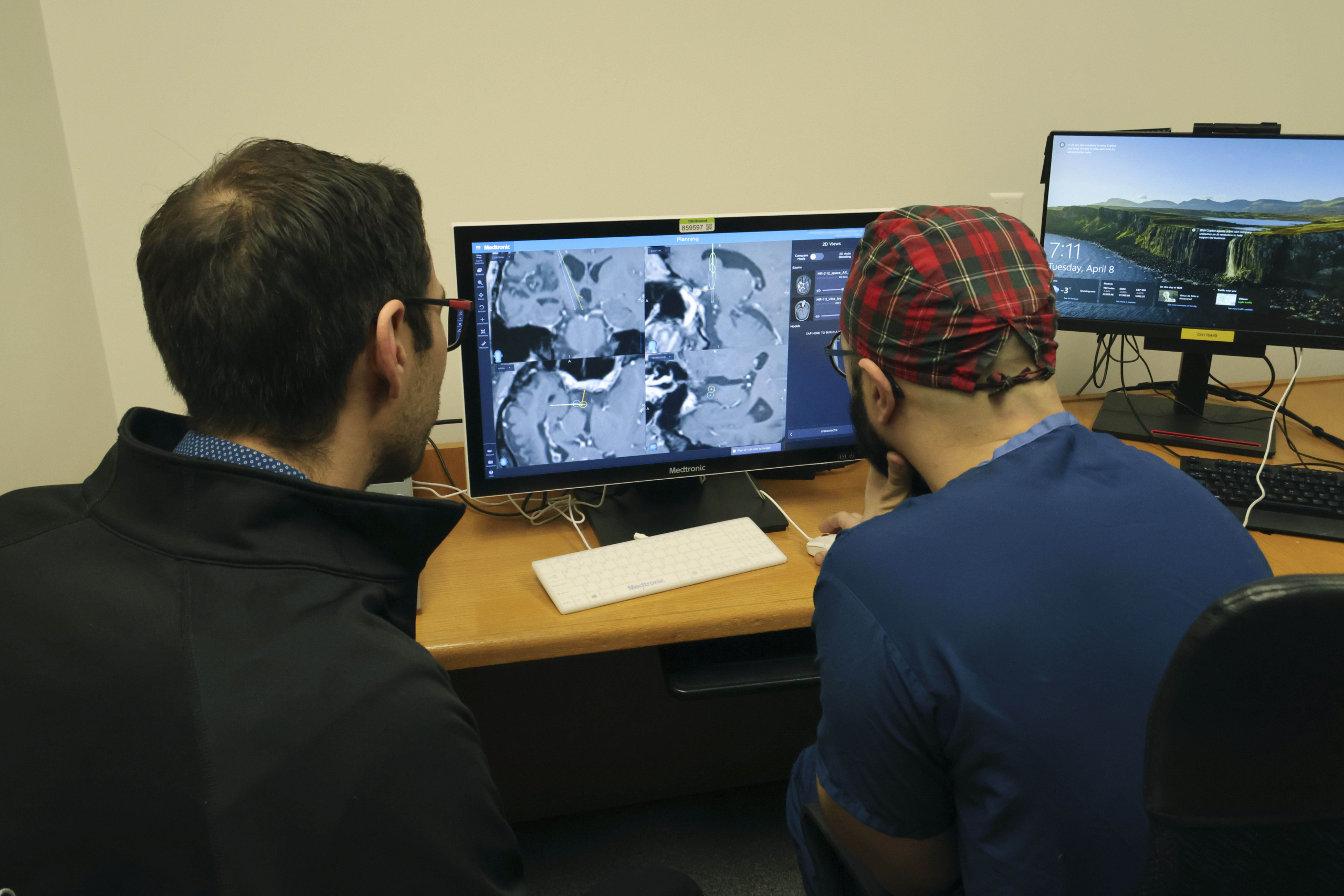

An EEG is the recording of brain waves by putting small electrodes on the patient’s head, which are connected to a computer, and recording electrical activity in the brain. It helps diagnose a variety of brain conditions.

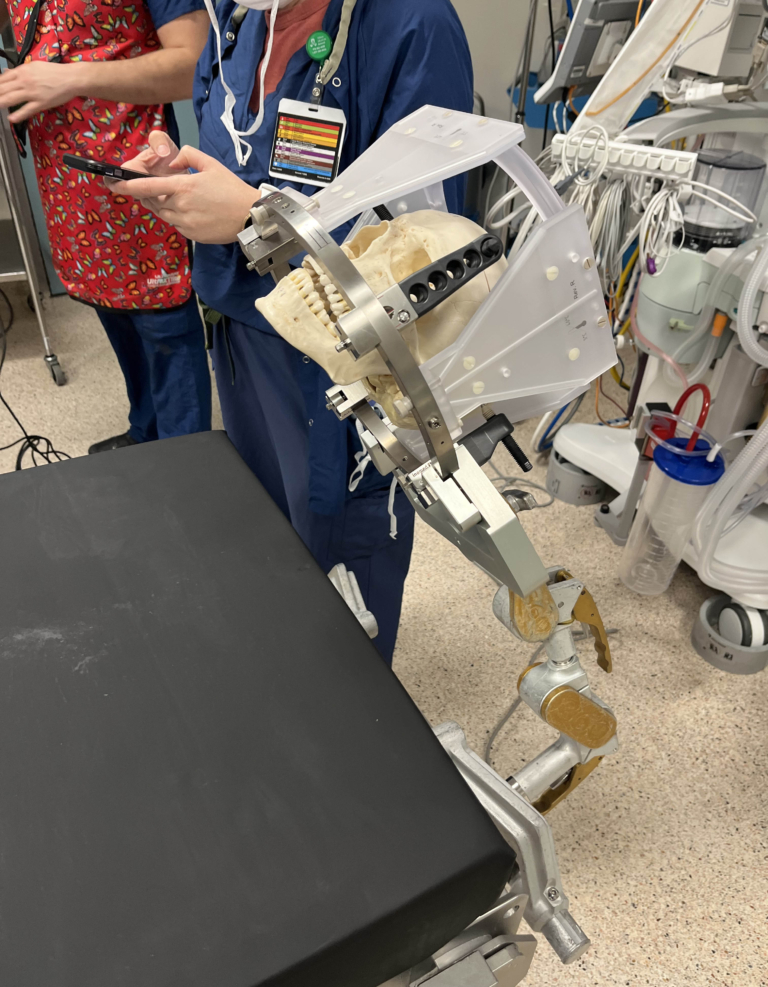

In contrast, the stereo EEG places these electrodes inside the brain through tiny pinholes. In January 2025, Dr. Chalil performed our hospital’s first-ever stereo EEG. This minimally invasive surgery identifies the precise areas in the brain where seizures originate.

“There could be anywhere between 10 to 20 electrodes per patient. We make a small nick in the skin, like a pinhole, and then drill into the skull,” he explains. “We have a defined trajectory — we know exactly where we are going and what structures we’re going to pass through to get to our target. Then we put the electrode in. It takes about 10 to 15 minutes per electrode.”

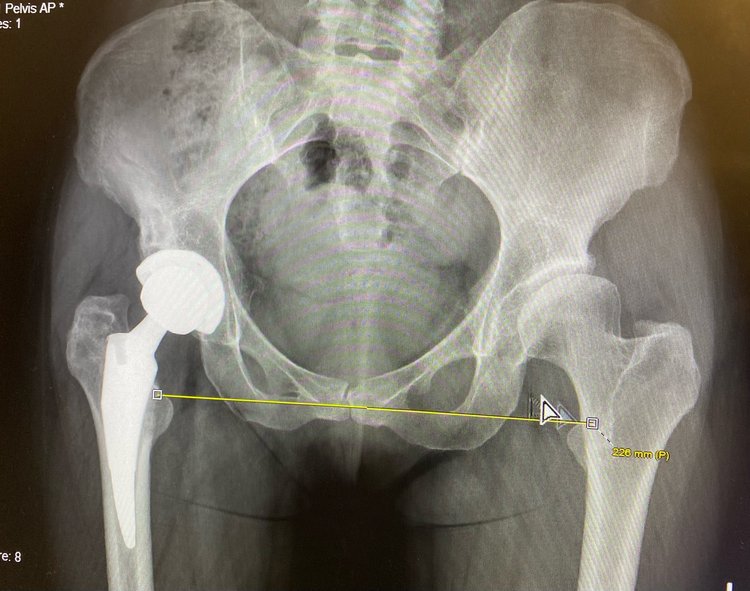

Once the patient wakes up, with the implanted electrodes, they get a CT scan. From there, Dr. Chalil will build a model for his colleagues on the neurology team that tells them where each electrode is placed in the brain. This helps determine where the seizure is starting and where it is spreading.

“The patient is then admitted to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) for a week or up to a month, sometimes even longer, until we get enough seizures to study,” he says.

The team then correlates the electrical signal they saw from the electrodes during a seizure, along with their previous information, and come up with a treatment plan. Treatment options can vary from removing a small section of the brain, to deep-brain stimulation, or even a newly acquired piece of technology called the radio frequency generator.

This new tech can be brought right to the patient’s bedside where Drs. Fantaneanu and Chalil can send an electric signal to generate a lesion that’s about 3 to 5mm thick. “It’s very small, but it’s very effective. And that lesion could cause a disruption in the epilepsy network and eliminate seizures up to 30% of the time,” Dr. Chalil explains.

While that number isn’t huge, he adds it’s reasonably effective because no other surgery is required.

“It's the last piece in a big picture to make Ottawa a centre of excellence for treatment of epilepsy.”

— Dr. Alan Chalil

As the team continues to further establish the program, they look to add new laser technology to provide patients with even better results, which can eliminate seizures from 60 to 75% of the time, depending on the type of seizure. They also hope to use these techniques in the coming year, driven in large part by an ongoing randomized controlled trial. “It’s called the slate trial, and it will give us a definitive number of comparisons between temporal lobe resection and laser ablations in treating a specific type of temporal lope epilepsy,” says Dr. Chalil.

For now, the completion of five stereo EEGs is a significant step. “It’s the last piece in a big picture to make Ottawa a centre of excellence for treatment of epilepsy. If we demonstrate that we can do it, interpret it safely, and produce meaningful surgeries out of it, then these patients will not need to travel anywhere else,” says Dr. Chalil.