Published: February 2026

Read time: 4 min 30 sec

Published: February 2026

Read time: 4 min 30 sec

It started with sudden, excruciating pain in his abdomen — the kind that jolts you awake at night. On a business trip in Barbados in March 2025, Ted Wagstaff was hit with a wave of stomach pain so severe it doubled him over. He couldn’t sleep for two nights straight. At first, he blamed the shrimp. Food poisoning, he told himself. It had to be. But when the pain returned a month later — this time a 12 out of 10 on the pain scale — he knew something was very wrong.

Preparing for the challenge

Ted has always been physically fit and mindful of what he eats. Whether running, lifting weights, or endurance training, being active is part of his DNA. Over the years, he has completed 16 Tough Mudder and Spartan Race events — gruelling 16–21 km extreme obstacle course races designed to test both physical and mental strength.

“I’m no stranger to pain,” says Ted. “But the pain in my abdomen was unlike anything I had ever experienced.”

A growing concern

Ted contacted his family doctor, who arranged for bloodwork, an ultrasound, and an endoscopy. After reviewing the results of his bloodwork and ultrasound, Dr. Stephanie Canning, a gastroenterologist at The Ottawa Hospital, noticed something worrying and asked Ted to come see her a week earlier than his scheduled procedure.

When he arrived at our hospital, instead of being taken directly for his endoscopy, Dr. Canning asked him to step into her office. Ted felt his concern start to rise.

The ultrasound detected an unusual mass in his abdomen, and Dr. Canning urged him to go to the Emergency Department at the Civic Campus for further, specialized testing. The results came back quickly and showed something Ted had never considered.

“When Dr. Canning came to see me in the hospital with the results of my CT scan, she pulled up a chair right in front of me. I knew then the news wouldn’t be good,” says Ted. “She told me the scan showed classic signs of lymphoma. My response was ‘WHAT ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT?!’ I thought I might have a stomach ulcer. I never considered cancer.”

Further testing followed, including blood tests, a PET scan, and a biopsy of the abdominal mass.

Results confirmed Ted had non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and it was already stage 3.

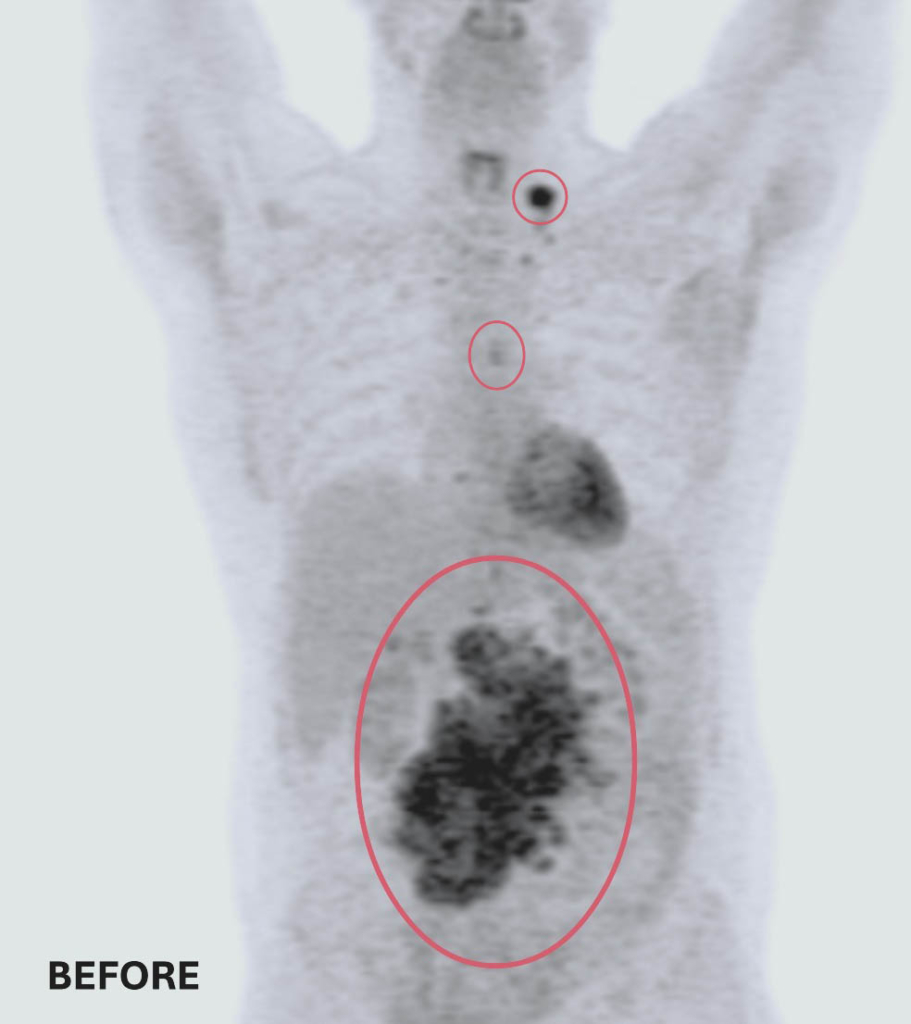

A PET scan revealed three masses. The largest and most concerning mass was in his abdomen and measured 14 by 9 centimetres — roughly the size and shape of an extra-large sweet potato. The other two were located near his esophagus and collarbone.

Meet Hematologist Dr. Kevin Imrie

The “double-hit”

Ted was referred to Dr. Kevin Imrie, Malignant Hematologist at The Ottawa Hospital.

Cancer care at The Ottawa Hospital is often delivered by a collaborative team of experts, so while Ted began his first round of chemotherapy, Dr. Imrie and a specialized pathology team continued detailed testing on Ted’s blood and tissue samples. This is the kind of advanced analysis required to fully understand the biology of cancer cases like Ted’s.

When those results came back, they revealed a curveball.

Further molecular testing confirmed Ted had “double-hit” lymphoma — a rare and aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for only about 5% of cases.

Because this subtype is less responsive to standard chemotherapy, Ted’s care team adjusted course quickly, designing an intensive and highly personalized treatment plan.

Subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The collective expertise of the “hive”

Ted’s care involved what Dr. Imrie describes as a “hive mind” approach, with close collaboration between hematology, pathology, nursing, medical imaging, and radiation oncology. Ted’s case was reviewed collectively throughout treatment, with specialists meeting regularly to assess scans, pathology, and response. “With this type of lymphoma, there’s no autopilot,” says Dr. Imrie. “The treatment plan is constantly reviewed and adjusted. Those decisions happen through collective expertise, and Ted was an active partner in that process.”

Surgery wasn’t an option for Ted due to the location of the largest mass, which sat deep within his abdomen near vital organs. Chemotherapy became the frontline treatment — but Ted’s aggressive disease required a more intensive approach than usual. Rather than a single-day infusion every 21 days, he received five days of continuous chemotherapy per cycle, delivered through an innovative, 24-hour infusion pump worn as a single shoulder backpack. The medication flowed through a catheter directly to his heart, allowing him to receive treatment as an outpatient while spending nights at home — a process made possible by The Ottawa Hospital’s robust outpatient program.

“One of the many strengths of The Ottawa Hospital is our cancer centre’s outpatient program,” explains Dr. Imrie. “It allows us to deliver treatment safely without admitting patients, which makes a big difference in their quality of life during what is often a long course of care.”

Over several months, Ted completed 26 rounds of chemotherapy — totalling 487 hours. His treatment included immunotherapy, which helped his immune system recognize cancerous cells and attack them, and abdominal injections to support white blood cell production, which protected against infection.

Since Ted’s cancer carries a higher risk of spreading to the brain, lumbar punctures were also performed as a preventative measure. Delivering chemotherapy directly into the fluid surrounding the brain can reduce that risk.

A remarkable response

Ted’s response to treatment was extraordinary. Follow-up scans showed the two smaller masses had completely disappeared, and the large abdominal tumour had shrunk to a tiny spot, smaller than a pea. Given the aggressive nature of double-hit lymphoma, Ted’s care team recommended a short course of radiation therapy to eliminate any remaining cancer cells — a precautionary measure to reduce the chance of recurrence.

Before and after treatment scans: Two of Ted’s three tumors completely disappeared. The remaining tumor was reduced to smaller than a pea — a remarkable response to treatment at The Ottawa Hospital.

Versa HD Radiation Technology

- As part of his treatment, Ted received radiation therapy from the Versa HD, one of the most advanced linear accelerators available today. A linear accelerator is a radiation machine that uses high-energy electrons or photons to treat cancerous tumours. Before each treatment, the Versa HD captures detailed imaging to confirm the exact location, size, and shape of the tumour. This allows physicians to adjustment treatment as needed, to ensure radiation is delivered with precision, minimizing radiation exposure to surrounding healthy tissue.

The “Toughest Mudder”

From the start, Ted approached his cancer journey with the same determination he brought to every Tough Mudder. Before starting treatment, Dr. Imrie asked him what his goal was. Ted didn’t hesitate — he wanted to complete another Tough Mudder. Even during chemotherapy, he stayed active, taking short walks and doing a few push-ups when he felt strong enough.

Ted tracked every scan, procedure, and treatment, checking each one off like an obstacle on a course. “Cancer became my toughest Mudder,” he says. “Every step, treatment, and scan I recorded and checked off. I treated it like a finish line I was moving toward.”

Remarkably, only five weeks after completing chemotherapy, Ted ran the Nashville Tough Mudder.

The gifts of cancer

Ted’s cancer journey was challenging, but he credits his mindset; the support from his wife Jacqueline, their three adult children, his extended family, and an incredible network of friends; and his care team with helping him endure what he calls “a marathon of the body and mind.”

Through it all, Ted noticed something unexpected — kindness. “I witnessed incredible acts of kindness from so many people,” he says. “This has been one of the many gifts of cancer. Small things like text messages to check in, drives to my chemotherapy treatments, and colleagues stepping in to cover my share of the workload in my business. It all made a difference.”

To celebrate the people who supported him throughout his journey, Ted hosted a Kindness Party, inviting friends, family, and his care team to honour the impact of care and generosity.

“Thanks to the advances we now have in lymphoma care, Ted has had a remarkable response to treatment and the outlook for cure is excellent”

— Dr. Kevin Imrie

Looking ahead

Ted is now in complete remission, and continues to be monitored closely, with regular bloodwork and check-ups every three months for the next two years, a standard follow-up schedule for his diagnosis.

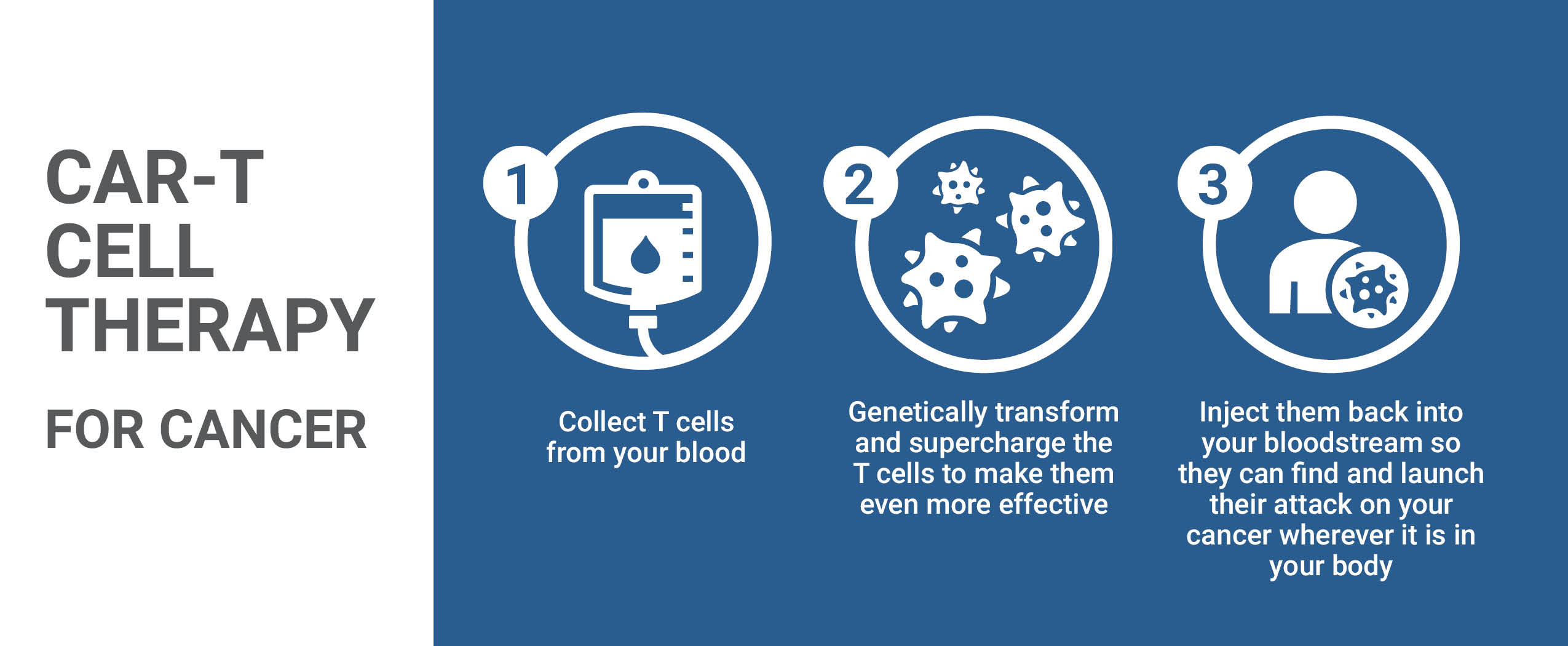

His remarkable response reflects how far lymphoma care has advanced in recent years — from more precise diagnostics to increasingly effective, personalized treatments. Innovations in immunotherapy and CAR-T cell therapy help more patients face even the most aggressive forms of the disease with hope.

“Thanks to the advances we now have in lymphoma care, Ted has had a remarkable response to treatment and the outlook for cure is excellent,” says Dr. Imrie. “In the past, if lymphoma returned, secondary treatment options were limited. Today, with therapies like CAR-T and other cutting-edge treatments, we have multiple lines of defence. While we don’t anticipate the cancer will return, we know that if it does, we are well-equipped to treat it effectively.”

“The care I received at The Ottawa Hospital was exceptional — world-class in every sense, and it made all the difference.”

— Ted Wagstaff

For Ted, that confidence reflects the care he experienced throughout his journey. “I’ve tried to remain positive throughout. I feel very lucky. The care I received at The Ottawa Hospital was exceptional — world-class in every sense, and it made all the difference.”

While navigating his cancer diagnosis and treatment, Ted was also preparing to welcome his first grandchild — a powerful source of hope and happiness during an uncertain time.