Published: September 2025

Read time: 3:30 mins

Published: September 2025

Read time: 3:30 mins

- In 2022, Karol Phillips developed blurred vision and was losing her balance

- Our experts found a large and rare brain tumour that required complex surgery done in an unusual position

- With no family nearby, meet the two people who were fixtures in her journey

- Find out what has happened following the procedure

Born in Georgian Bay and raised on an apple farm, Karol Phillips has called Ottawa home for 22 years. She’s a Wealth Advisor Assistant at an investment firm, with a love of travel, music, and animals. However, in January 2023, after months of symptoms, tests revealed she had a rare brain tumour. That’s when she turned to The Ottawa Hospital’s specialized neurosurgical team, who were ready for the complex surgery that awaited her.

It all began in 2022 when Karol started experiencing vision problems, particularly blurred vision on the left-hand side. She also noticed discomfort in her neck and remembers becoming unstable, as she describes it. “I was losing my footing when I walked. I fell a couple of times without being dizzy, without losing consciousness or anything. I just randomly fell.”

That’s when her family doctor set in motion a variety of medical tests, from cardiac to blood work, and then an MRI of her brain in late 2022. “By this point, I was having trouble holding up my head. I couldn’t sit in one spot. I was only comfortable when I lay down. It wasn’t pain, it just felt so heavy,” recalls Karol.

Hard to process the news of a brain tumour

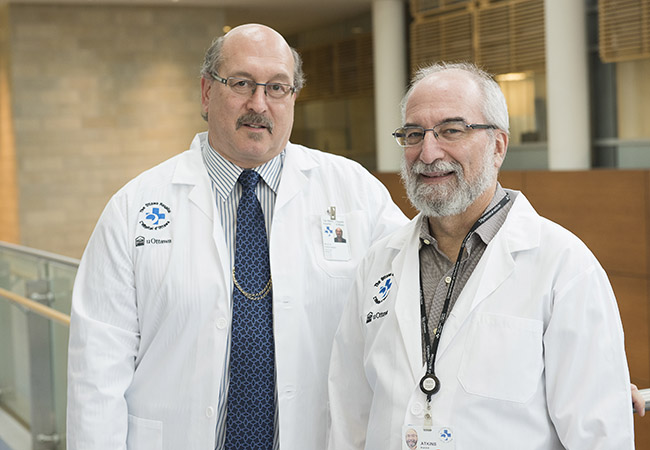

When the results came in, she was referred to The Ottawa Hospital’s neurosurgical team at the Civic Campus. That’s where she met two people who would become key fixtures in her care journey — Dr. John Sinclair, Director of Neurosurgical Oncology and Director of Cerebrovascular Surgery, and Jessica Lucky, a physician’s assistant, who works alongside Dr. Sinclair.

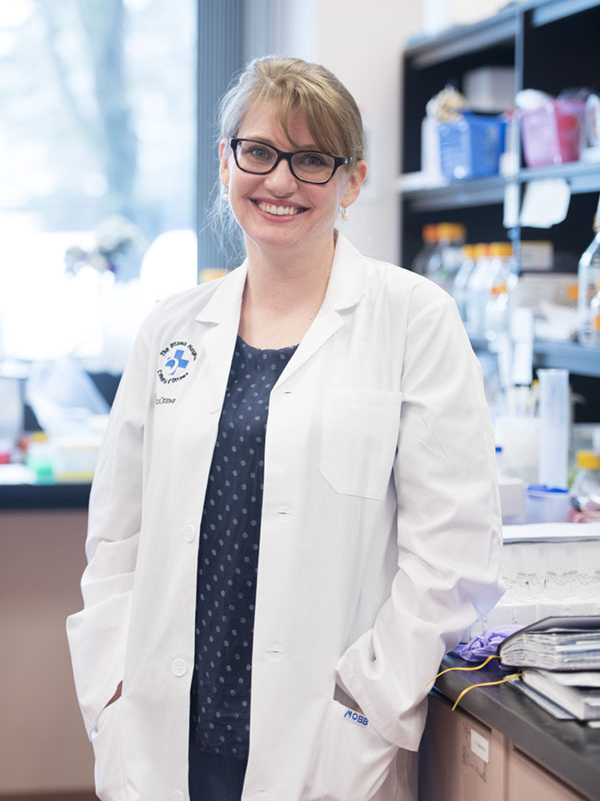

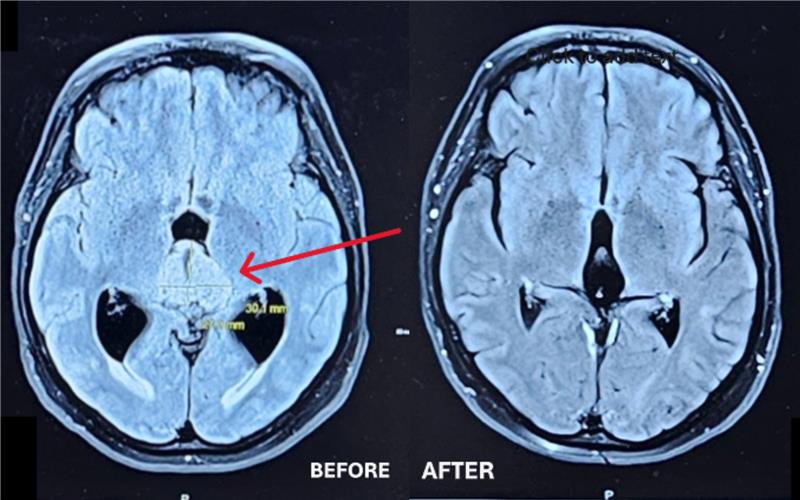

It was on that snowy January day when Jessica revealed to Karol that the MRI results showed a brain tumour — the size of a lime. “Her imaging was impressive, I’ll never forget it because of the size of tumour itself and the location of it,” recalls Jessica.

“It was shocking. I didn’t even know how to process it."

— Karol Philips

Remembering the day still brings tears to Karol’s eyes. “It was shocking. I didn’t even know how to process it. I was alone for the appointment. I don’t have family in Ottawa, and I was scared. But Jessica was wonderful,” explains Karol. “Then she brought in Dr. Sinclair. He told me everything was going to be ok, and they would take care of me.”

Meet neurosurgeon Dr. John Sinclair

Meet Physician Assistant Jessica Lucky

A complex neuro case

Karol was presenting two different problems at once — she had a brain tumour in the back part of the brain stem known as the pineal region of the brain, and she had a condition called hydrocephalus. That meant there was a buildup of fluid in the brain, because the tumour was pressing on the brain stem and blocking the pathway for the normal flow of fluid through this region.

“In all the areas of the brain where we have tumours, this is one of the least common. I see one or two patients who need surgery every year, but in the year that Karol was diagnosed, we had five or six patients with tumours in this region.”

— Dr. John Sinclair

Normally, to deal with that fluid buildup, a drain or a shunt would be used, but as Dr. Sinclair explains, what Karol faced was rare. “In all the areas of the brain where we have tumours, this is one of the least common. I see one or two patients who need surgery every year, but in the year that Karol was diagnosed, we had five or six patients with tumours in this region.”

As a neurosurgeon who sees hundreds of patients a year, it’s these cases that stand out because the operation is unique — it’s done with the patient in a sitting position. Most patients who have brain tumour surgery are lying down on their back, their side, or face down, but for this type of tumour, the operation is quite different.

“This region of the brain requires the patient to be sitting at 90 degrees. The head is opened just above the top of the neck which exposes a tiny little corridor between the cerebellum and the overlying hemispheres of the brain. When the patient is sitting, the cerebellum falls away from the upper part of the brain due to simple gravity and allows access to the area where the tumour is located,” explains Dr. Sinclair.

A giant pre-operative setup for a unique brain surgery

This unique procedure requires a significant operative setup in terms of the anesthesia, neurophysiologic monitoring of the brainstem, and from a nursing perspective. “Our neurosurgery nursing care facilitator, Francine Robinet-Leduc, is always the one to lead this set-up. There is a significant amount to coordinate, including special instrumentation that goes on the bed which is unique for this surgery,” says Dr. Sinclair. “It’s a special frame that holds the patient safely in a sitting position for the surgery. It has to be specially installed and checked to maneuver the bed in case of an emergency during the operation.”

After the initial meeting with Dr. Sinclair and Jessica, Karol underwent a litany of tests in preparation for surgery. Due to location in the brain, all signs pointed to a pineal tumour, and the team believed it was likely benign in nature.

The complex, 7-hour surgery took place in April 2023. Karol’s family and friends rallied around her, including her mother, who, like other family members, travelled hundreds of kilometres to be by her side.

“It’s a very unusual tumour to begin with, arising from neuronal cells of the brain, and to have one in that area of the brain is even more unusual."

— Dr. John Sinclair

The pineal region is situated in the very centre of the brain, making the removal of tumours in this area a technical challenge, according to Dr. Sinclair. However, it was successfully removed from the brainstem without any complications before the team got a surprise in the type of tumour it was — pathology tests confirmed it was a very rare tumour termed a central neurocytoma.

“It’s a very unusual tumour to begin with, arising from neuronal cells of the brain, and to have one in that area of the brain is even more unusual. But fortunately for her, it was benign in nature, as opposed to others tumours that can occur in this location that can be much more dangerous in terms of malignancy.”

Deep gratitude for exceptional care

Karol remained in the hospital for two weeks, most of which was spent at the Neuro Acute Care Unit (NACU) at the Civic Campus. She needed the support of a walker to stabilize her when she was discharged and physiotherapy to build up her strength. “It took me a good year of physio to recover. I started with short walks down the street with the walker, then I used the cane for a few months. The cane still sits in my closet now as a reminder of how far I’ve come,” she says.

Because the tumour was benign and completely removed, Karol didn’t require any other treatment. She had MRIs every six months post-surgery, and in January 2025, Jessica gave Karol the great news that she didn’t need to return for a year.

She returned to her job and her work family in January 2024 and is beyond grateful. “I feel gratitude every day. I think how lucky I am, and I truly appreciate the little things. Recently, I walked to my car and saw some lilacs, so I smelled them. I’m stopping to smell the flowers!”

Travel is also something Karol is back to enjoying. Her first trip post-surgery was to Boston for a weekend with her best friend. When she felt strong enough, she and her friends travelled to Norway in 2024.

She’s deeply grateful for the care she received. From Dr. Sinclair to Jessica to the NACU team, and she’s expressed her thanks in a variety of ways, including the Gratitude Award program and proceeds from her office’s annual summer golf tournament in 2025, which supported The Ottawa Hospital.

“The care I received was life-changing. Dr. Sinclair — he saved my life.”

— Karol Philips

And Jessica was Karol’s constant throughout this journey. For Jessica, that’s why she loves her job. “There’s nothing that makes me happier than a patient saying they feel ready for surgery — they feel comfortable, they feel confident. Their questions are answered.”

While Karol looks forward to the day when she is completely released from the neuro team at The Ottawa Hospital, she will always be grateful they were there and ready when she needed them. “I went from zero to brain surgery at 51. I had never even broken a bone in my life or needed a hospital.”

Listen Now:

- In 2022, Karol Phillips developed blurred vision and was losing her balance

- Our experts found a large and rare brain tumour that required complex surgery done in an unusual position

- With no family nearby, meet the two people who were fixtures in her journey

- Find out what has happened following the procedure