A resident of Goose Bay, N.L., most of his life, John Bookalam lives for the outdoors. He loves adventures, including international cycling and skiing in the winter. The retired guidance counsellor cherishes that time even more today, after a harrowing medical diagnosis unexpectedly led him to The Ottawa Hospital for neurosurgery.

It all began in late winter of 2017 when John returned from teaching a ski lesson. He was unloading his gear from his SUV when he hit the back of his head hard on the hatch door. Initially concerned he might have a concussion, John quickly eliminated the possibility thanks to his first-aid training. However, a week later, he followed up with his family doctor and an ultrasound revealed what appeared to be a hematoma, a collection of blood outside a blood vessel, which would normally resolve itself. “But the next week, I had to see my doctor again and the hematoma went from four centimetres on the ultrasound to eight centimetres,” says John.

“I was so nervous. I could hardly think.”

— John Bookalam

The situation turns dire

John’s care team in Goose Bay closely monitored him for many weeks. However, by the end of May, he developed symptoms similar to the flu. “I was burning up. I was on fire and I immediately went to the emergency department of my local hospital. Those symptoms would be a bad omen,” says John.

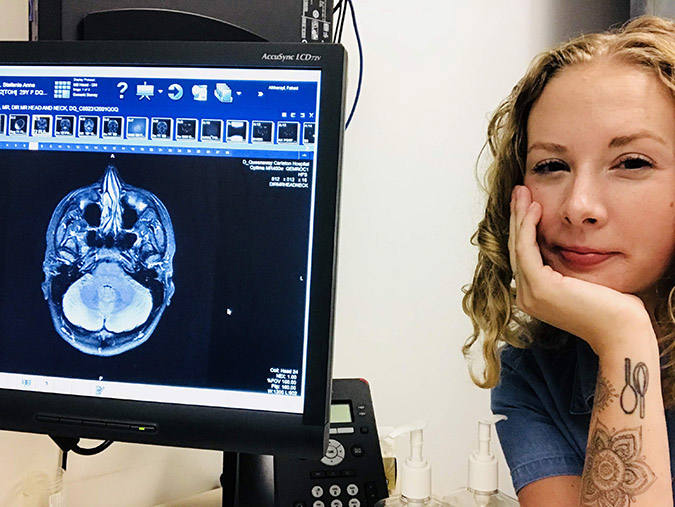

A CAT scan revealed the hematoma had grown from eight centimetres to 10.6, and the situation was becoming dire. He needed a skilled neurosurgery team to help him — a team that was not available in Newfoundland and Labrador. With roots back in Ontario, he turned to his dear friend, Nadia Marshy, from the Ottawa area for guidance.

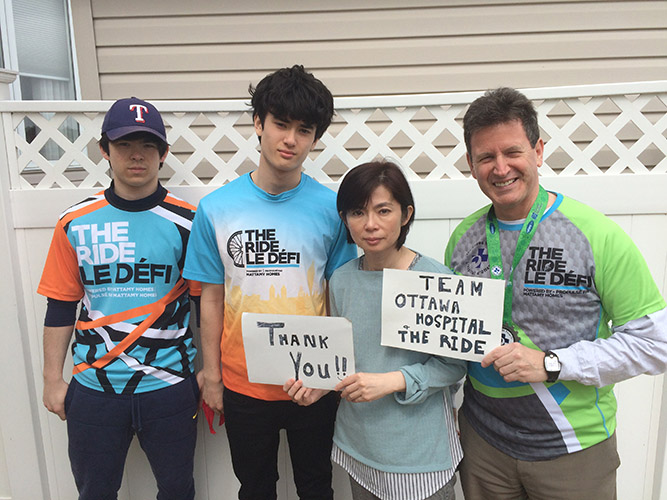

Nadia vividly remembers the day she got the call from “Labrador John,” a nickname she gave him through their cycling adventures. She was sitting at her desk when she picked up the phone — John was at his wit’s end. “I knew he’d been hit hard on the head and it had caused a large bump. That was weeks earlier, so I presumed that he was all healed up by now. John proceeded to tell me that not only was the bump much larger, but he was in constant pain,” recalls Nadia.

“She played a vital role in identifying The Ottawa Hospital as an emergency life-line to receive lifesaving surgery.”

— John Bookalam

Calling on our neurosurgery experts for help

Following that call, Nadia was beside herself and she knew her friend was in a medical emergency. “Here I was sitting in my sunny downtown Ottawa office with The Ottawa Hospital and all of its innovation and world-class services next door, and there was my dear friend with this massive, infected lump the size of a grapefruit in desperate need of help and so far away.”

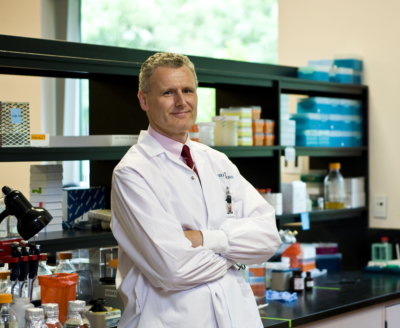

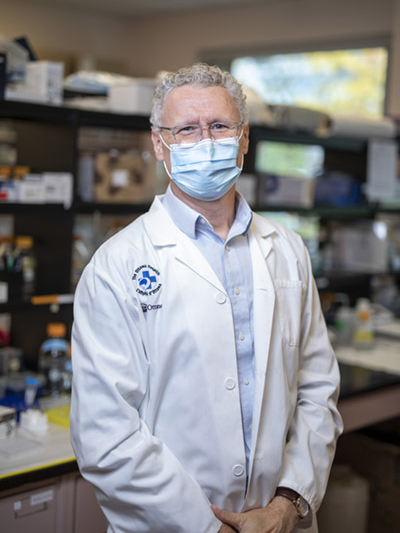

Next, Nadia worked to get John in touch with the neurosurgery department at our hospital — she had witnessed the skill firsthand in 2012 when Dr. John Sinclair performed two lifesaving surgeries on someone close to her. “I gave Labrador John the contact information, and within a few short days, he was on a plane to Ottawa,” explains Nadia.

John credits Nadia for helping save his life. “She played a vital role in identifying The Ottawa Hospital as an emergency life-line to receive lifesaving surgery.”

Once John landed at the Ottawa airport, he went straight to the Civic Campus with all his documents in hand. He met with neurosurgeon Dr. Howard Lesiuk and plastic surgeon Dr. Daniel Peters and handed them his scans to review. They determined the situation was worse than anticipated, and John would need surgery as soon as possible. “I was so nervous. I could hardly think,” recalls John.

A shocking discovery

The surgery would be long and difficult, and it uncovered something far worse than John had ever imagined when he embarked on the trip to Ottawa. Doctors discovered a non-Hodgkin lymphoma tumour on the back right-hand side of his skull and part of his skull was badly infected. While the news was devastating, John recalls the reassuring words that came from Dr. Peters before surgery. “He said I had a strong heart and tremendous lungs, and both would help me during the complicated surgery.”

“We are blessed to have some of the best minds and the most skillful surgeons on the planet right in our backyard. I am convinced what they did for Labrador John is what no one else could have done, and ultimately saved his life.”

— Nadia Marshy

While the news was devastating, Nadia recalls after the surgery, the pain John had experienced for so many weeks was already subsiding. “He received incredible care. The night before his surgery, he was weak, in agony, and couldn’t hold his head up for any length of time because of the pain and the weight of the mass on his head. The next day, he was able to lie on his head and rest in comfort,” says Nadia.

Next, John was transferred to the Cancer Centre at the General Campus for testing to learn more about the tumour. “I underwent a lengthy procedure by an incredible team to diagnose my lymphoma type.”

Primary central nervous system lymphoma

Diagnosed with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), John began chemotherapy treatment here in Ottawa before returning home where he would continue his care at the St. John’s Cancer Centre.

Primary central nervous system lymphoma is an uncommon form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It starts in the brain or spinal cord, in the membranes that cover and protect the brain and spinal cord, or in the eyes. This type of cancer is more common in older adults with the average age at diagnosis being 65.

Further testing revealed John had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma – BB Expressor — an aggressive type of lymphoma.

However, after months of treatment, good news came on February 26, 2018, when John learned he was cancer free.

“After almost four years, I’m cancer free and I’ve healed after three head surgeries. I’ve resumed my cross-country skiing and marathon road cycling.”

— John Bookalam

Not yet out of the woods

His journey, though, was far from over. John returned to Ottawa for one more surgery for skull base osteomyelitis — an invasive infection. Other treatments back home didn’t prove helpful and, once again, John required specialized care.

A highly skilled team at The Ottawa Hospital came together again to perform another difficult surgery. They would use a procedure called debridement and they would need to produce a new blood supply to the area. Debridement is when the surgeon removes as much of the diseased bone as possible and takes a small part of the surrounding healthy bone to ensure they have removed all infected areas. “They scraped the bone down until there was no sign of the infection and then did skin grafting on the back of my head,” explains John. The second part of the procedure was even more complex and involved taking an artery from his back, transplanting it to his head — creating a vital blood supply from his ears to the back of his skull. “I thank plastic surgeon, Dr. Sarah Shiga for being there in my time of need. If it were not for team Shiga and Lesiuk, I would never have achieved the quality of life I have today.”

“I owe much gratitude to the surgeons and staff at The Ottawa Hospital. Hopefully, my story will inspire others to donate so others can regain a quality of life as I have in abundance today.”

— John Bookalam

As a result of the debridement, he lost a significant amount of bone at the rear of his skull. Today, he must be very careful — he wears a helmet even when he’s driving to protect his brain, but his adventures continue. John’s grateful for each day and each outing he’s able to plan. “After almost four years, I’m cancer free and I’ve healed after three head surgeries. I’ve resumed my cross-country skiing and marathon road cycling.”

Nadia is also grateful for what she witnessed. “We are blessed to have some of the best minds and the most skillful surgeons on the planet right in our backyard. I am convinced what they did for Labrador John is what no one else could have done, and ultimately saved his life.”

Labrador John continues to say thank you

John’s gratitude goes beyond just words. He started by recognizing his care team through our Gratitude Award Program. While it was an important way for him to say thank you, it’s the special note he got in return from Dr. Shiga, who was a part of the second surgery, that made the donation extra special. “She wrote me a beautiful, personal handwritten letter. That’s one of the best letters ever sent to me,” says John.

The 73-year-old didn’t stop there though. He became a member of the hospital’s President’s Council when he committed to support our hospital with a donation of $1,000 a year. “I owe much gratitude to the surgeons and staff at The Ottawa Hospital. Hopefully, my story will inspire others to donate so others can regain a quality of life as I have in abundance today.”

Nadia is just as happy to see her friend back living his active life. “To see Labrador John fully recovered and cycling up challenging hills and covering incredible distances is fantastic. Those surgeons gave him his life back. He never takes a moment for granted,” says Nadia.

And John says he never will. “I will always donate that $1,000 a year to The Ottawa Hospital until I pass from the earth.”

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.