Published July 2020

We each have a defining moment in our life — a moment that changes our life forever. For some, that moment is not as clearly defined as it is for others. For Kimberly Mountain, that moment was the discovery of a cancerous brain tumour.

In February, 2011, Kimberly was 28 years old and out with her then-boyfriend, Matt Mountain, when she felt a weird, strong twitch on the right side of her face as they were driving. “Then all I remember is waking up. Our car was pulled over on the side of the highway. Paramedics were there, and I heard Matt say, ‘Kim just had a seizure’,” recalls Kimberly.

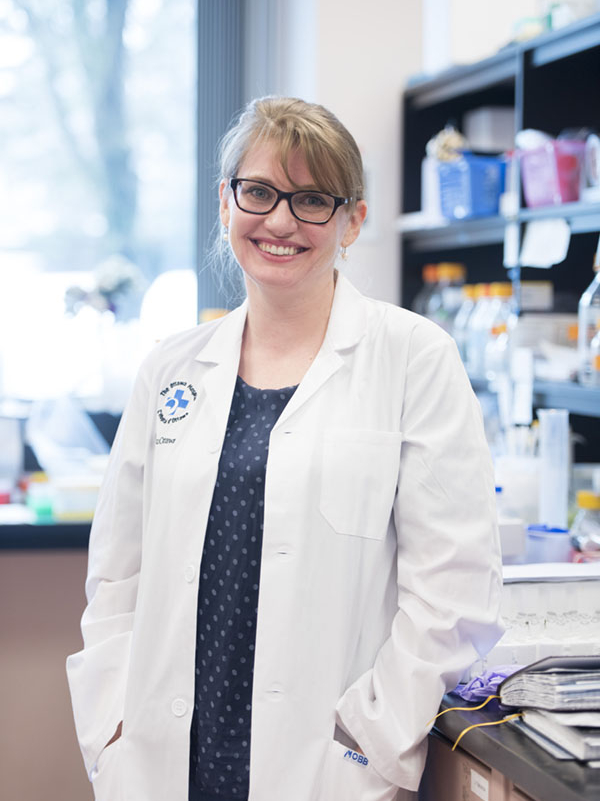

Kimberly was rushed by ambulance to the trauma centre at the Civic Campus of The Ottawa Hospital. She would have another seizure, and then an MRI revealed a brain tumour on her right frontal lobe. That moment changed her life.

For two weeks, The Ottawa Hospital became Kimberly’s second home. Her family and Matt never left her side. “Oddly enough, my memories of being in the hospital aren’t of a sad time at all. They are actually some of my favourite memories, filled with friends and family. Everyone I loved was there. And we made friends with the amazing nurses and staff,” says Kimberly.

Awake brain surgery

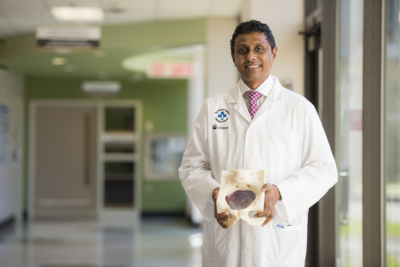

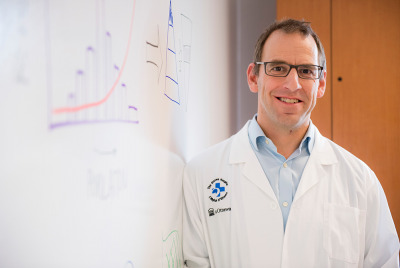

On March 7, 2011, Kimberly had brain surgery. Her surgeon, Dr. Charles Agbi, would keep her awake for the operation. This is a highly specialized surgical procedure that requires a team approach led by an experienced neurosurgeon and a neuroanesthesiologist. It enables the neurosurgeon to remove tumours that would otherwise be inoperable because they are too close to areas of the brain that control vision, language, and body movement. Regular surgery could result in a significant loss of function. By keeping Kimberly awake, the medical team was able to ask her to move certain body parts and speak during the procedure.

When she thinks back to the operation, she remembers never being worried. “I guess the hospital staff had made me feel safe and confident.”

During surgery, Kimberly could feel the vibrations of the team drilling into her head, but she didn’t mind it. “I kept talking, laughing, and singing Disney songs, like “Hakuna Matata.” I was telling them how I was going to go to Disney World when it was over. Five hours seemed like just one,” says Kimberly.

For Dr. Agbi, this type of interaction is critical to the success of the surgery. “If they’re only answering questions [surgery staff] are asking them, sometimes we might miss something.”

Transformational technology

It is advances in technology like Kimberly experienced that allow neurosurgeons at The Ottawa Hospital to provide transformational care.

In fact, donor support brought a specialized microscope to Ottawa, allowing surgeons to perform fluorescence-guided surgery. The technique requires patients to drink a liquid containing 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) several hours before surgery. The liquid concentrates in the cancerous tissue and not in normal brain tissue. As a result, malignant gliomas “glow” a fluorescent pink color under a special blue wavelength of light generated by the microscope. This allows surgeons to completely remove the tumour in many more patients, with recent studies showing that this can now be achieved in 70 percent of surgeries compared to the previous 30 percent average. The first surgery of this kind in Canada was performed at The Ottawa Hospital.

“Dr. Nicholas sat down, held my hand, and said the word — cancer. Everything went blurry, and this time I couldn’t stop the tears. I had been strong up until that moment.” – Kimberly Mountain

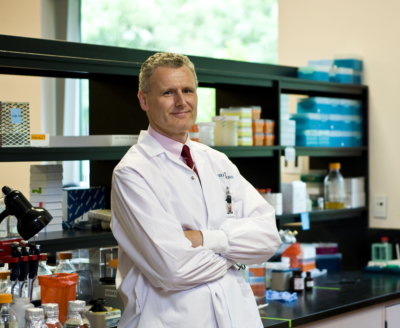

Oncologist reveals brain tumour is cancerous

When pathology tests on the tumour came back several weeks later, Kimberly met with her oncologist, Dr. Garth Nicholas, and he revealed the news she feared the most. “Dr. Nicholas sat down, held my hand, and said the word — cancer. Everything went blurry, and this time I couldn’t stop the tears. I had been strong up until that moment,” remembers Kimberly.

During her cancer treatment, Kimberly faced 30 rounds of radiation, followed by chemotherapy. Matt, who had proposed during Kim’s long stay in the hospital, took her on trips to amusement parks or convertible drives to help get her through the difficult times. The couple even made a special trip to Disney World. “All I could think of during my brain surgery was how happy and carefree it was there. The world was suddenly much more exciting, and I was aware of every little smell, feeling, and moment—something I think maybe only cancer patients can appreciate.”

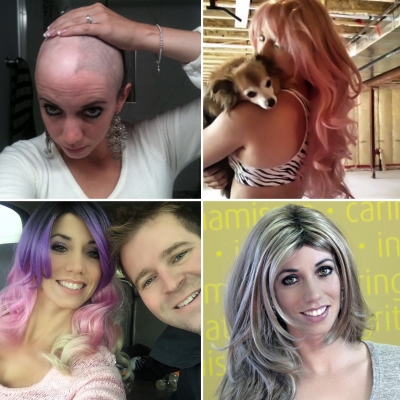

This all provided Kimberly with a distraction from the side effects, the tiredness, and the hair loss. Losing her hair was one of the most difficult parts of treatment. “I hated losing my long, beautiful hair.”

Less than a year later, on January 6, 2012, Kimberly received her last chemotherapy treatment. “I asked those pills to eat that cancer.” Her wish would be realized when an MRI could not detect any residual cancer. Kimberly transformed into a cancer survivor.

Through a mother’s eyes

Kimberly has become known for never showing up for an appointment without a small contingent of supporters. She always has her family by her side, including her mother, Cyndy Pearson. Cyndy laughs that Kimberly always has an entourage—even when she learned her tumour was cancerous. “We were all there. When there’s something important, we’re all there. When Dr. Garth Nicholas leaned over, and said, ‘Kim you have cancer,’ we were all crying.”

Cyndy is grateful to The Ottawa Hospital for saving Kimberly, her youngest of three children. She points out March 7, 2011 is a new date circled on the family’s calendar—Kimberley’s re-birthday.

Cyndy is also forever grateful for Dr. Agbi’s care. “If this surgery hadn’t happened, she wouldn’t be having any more birthdays. If the hospital had not been able to save her…” Cyndy’s voice trails off.

“Even if the cancer does come back, I am confident that The Ottawa Hospital will be able to save me again, thanks to its constant innovative research and clinical trials that are making treatment better and saving lives.” — Kimberly Mountain

Cancer survivor ten years later

Today, Kimberly has a tattoo on the back of her neck that reads “Hakuna Matata – March 7, 2011”. She celebrates every milestone — including being cancer free — with family, friends, and of course Matt, who never left her side and who is now her husband. You could say it’s like a Disney ending.

Not everything went back to normal. “My precious hair will never be the same,” says Kimberly. “There’s a big spot where my hair will never grow back. The whole right side of my head is permanently bald.” However, always finding the positive, Kimberly says she can do her hair in ten seconds these days, thanks to a few different wigs, “I may actually own more wigs than shoes.”

All joking aside, Kimberly is grateful for each day. “Even if the cancer does come back, I am confident that The Ottawa Hospital will be able to save me again, thanks to its constant innovative research and clinical trials that are making treatment better and saving lives.”

For now, Kimberly takes it one day at a time, celebrating life’s little moments each day.

Hear Kimberly Mountain on Pulse: The Ottawa Hospital Foundation Podcast.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.