“We are the only Level 1 Trauma Centre for adults in eastern Ontario, so we see the most critically injured patients from all across the region, including Quebec in certain circumstances. Our team has the capacity to handle almost any injury.”

– Dr. Maher Matar

As darkness falls over the city and most are sleeping, that’s when many of our patients arrive at the Trauma Centre. My name is Maher Matar, I’m a trauma surgeon at The Ottawa Hospital, and it’s not unusual to be jolted out of a sound sleep in the middle of the night after a Code One is called. I have just minutes, 20 minutes to be exact, to pull myself together, arrive at the Emergency Department (ED) of the Civic Campus, and join the rest of the trauma team that has assembled. All of us are ready and functioning at 110%. Lives depend on it.

The only Level 1 Trauma Team for adults in the region

We are the only Level 1 Trauma Centre for adults in eastern Ontario, so we see the most critically injured patients from all across the region, including Québec in certain circumstances. Our team has the capacity to handle almost any injury.

Our team includes a trauma team leader like myself, as well as an anesthesiologist, a team of emergency nurses, a group of resident physicians, and respiratory therapists — this allows us to be ready for the wide variety of complex cases that we handle, or when a Code One is called.

A Code One means a patient with significant injuries is coming to the hospital and we need all resources gathered at the ED. It could be a few patients involved in a high-speed motor vehicle collision or a single patient that fell down the stairs. By contrast, a large-scale incident like the Westboro bus crash or any other community disaster results in a Code Orange being called

Life as a TOH Trauma Surgeon

Life as a TOH Trauma Surgeon

Snowmobile crash brings life-threatening injuries

Back on January 18, 2020, I was jolted awake from the comfort of my warm bed, when I got a call in the middle of the night from a nearby Québec hospital. They had a patient with a transected aorta – that means the aorta, the main blood vessel that travels from the heart, had ruptured or torn. When I heard that, I knew the patient’s chances of making it to our hospital were slim.

His name was Cody Howard, and while visiting from Arizona, he had been in a snowmobile crash in Ripon, Québec, about 70 minutes from Ottawa. The fact that he made it to the first hospital was hopeful, but with this type of injury, he could suddenly crash. Cody needed our expertise to help save him.

I began caring for Cody on that phone call, explaining to the team on the other end of the phone what medications should be started and how Cody should be transferred to our Trauma Centre.

“The patient was lying flat and, incredibly, he was awake and alert. He knew he was in a very precarious situation.”

– Dr. Maher Matar

As I drove to the hospital, I called Cheryl Symington, a charge nurse who was working in the ED that night. She’s a team lead and she’s amazing. I told her “This is a bad one. I need everyone on deck.”

The trauma team is ready

I immediately called the vascular surgery team and told them to be on standby as soon as Cody arrived.

Cody made it to the Trauma Centre with his younger brother, Trevor Howard, who had not been involved in the crash. Cody was lying flat and incredibly, he was awake and alert. He knew he was in a very precarious situation. In fact, even a small movement could have been fatal. We did our assessment from A to Z, the same way we do it every single time, making sure we don’t miss any injuries. As this is happening, I’m on the phone with Dr. Prasad Jetty, a vascular surgeon. He also consulted with a cardiac surgeon, Dr. Fraser Rubens. You know, we’re lucky to have that kind of skill close by at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute.

“In my 30 plus years as an ED nurse, that was by far the most difficult yet most rewarding night. Dr. Matar, Dr. Jetty, and Dr. Reubens are each highly skilled specialists in their fields. Together they are a team beyond description. The stars aligned that night.”

– Cheryl Syminton

Dr. Rubens came to the trauma bay – a cardiac surgeon rarely comes to the trauma bay – that’s an indicator of the severity of this injury. At this point, the three of us were discussing the patient and we agreed he had a very high chance of dying on the operating table; there was also the potential for paralysis. Everything happened fast – this all took place in the first 30 minutes of Cody arriving.

Making the difficult call to the family

I then called the patient’s father in Arizona who also happens to be a doctor. I had to tell him the grim news. However, I promised him the people taking care of his son were the best in the entire region. I told him to focus on getting to Ottawa and that we’ll take care of the rest.

It’s never easy making those calls. Breaking bad news to family members or letting someone know their loved one is going in for a very serious surgery – it weighs on you. Thankfully, social workers at our hospital are always there to help. If I’m busy caring for the patient, a social worker receives the family and updates them on what’s going on. They play an immense role in our ED.

More injured patients arrive

As Cody’s surgery plan was being made, his brother, Trevor, came up to me and said, ‘there are two more of us’ I said, ‘excuse me?’ I was shocked! He explained that another brother, Bret, and his brother-in-law were also injured in the snowmobile crash and were still at a nearby hospital in Québec.

“I promised him the people taking care of his son were the best trained in the entire region. I told him to focus on getting to Ottawa and we’ll take care of the rest.”

– Dr. Maher Matar

That’s when the compassionate side of caring plays a key role in the work we do – in the work we all do. We can’t have the family arrive in Ottawa and have to go back and forth between two hospitals, worried about their injured kids. They were already dealing with enough stress and needed to be together.

We called the other hospital and we arranged for immediate acceptance of the two family members, regardless of the extent of their injuries. While the brother-in-law had only minor injuries, Bret, had a significant head injury along with an injury in the abdomen. I needed to get him to the operating room to repair a ruptured bladder. The vascular surgery team and cardiac surgery team took Cody for surgery at the Heart Institute and I took Bret into emergency surgery at the Civic Campus, simultaneously.

A successful night as lives are saved

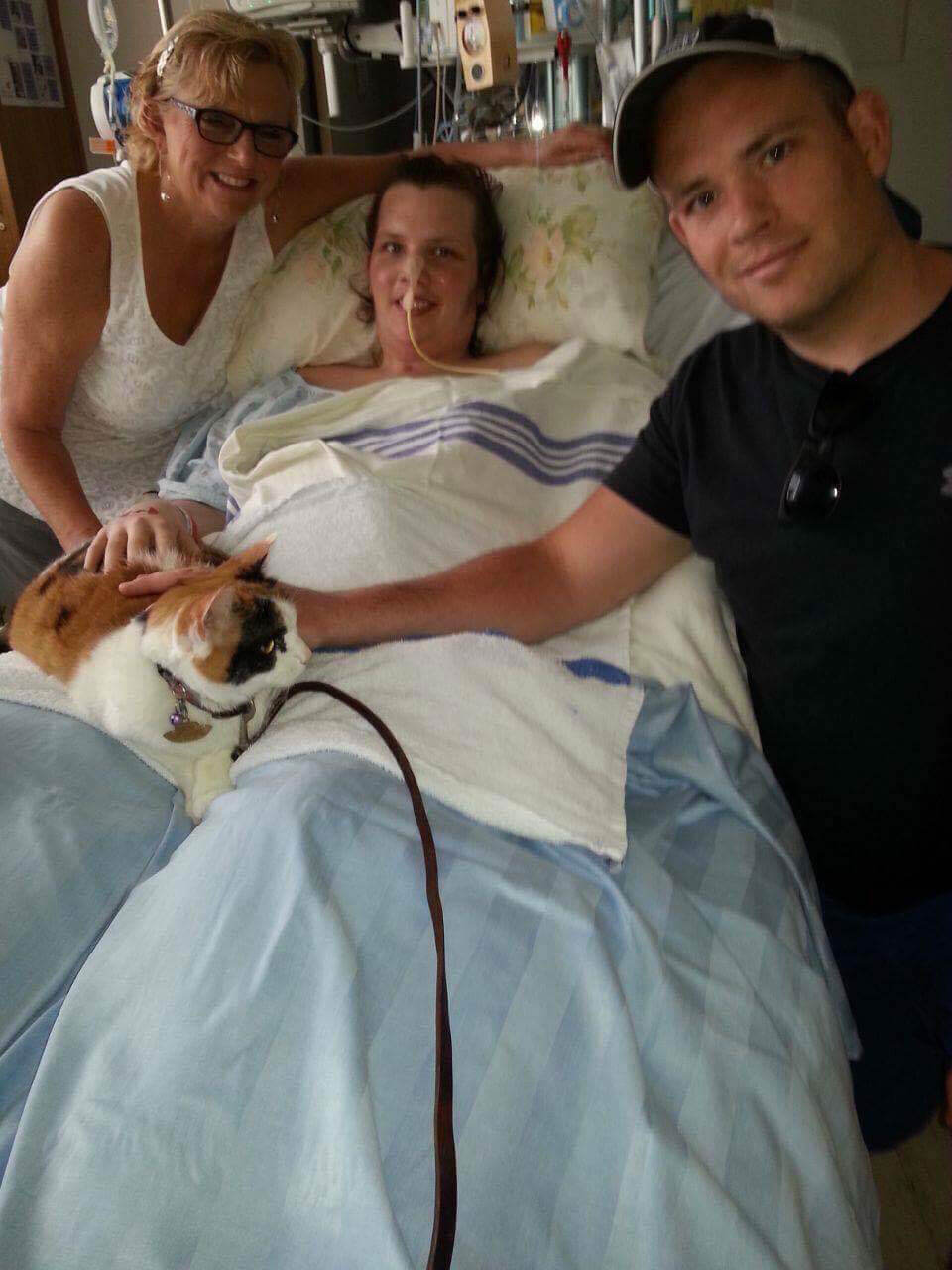

Bret made a quick recovery. After 10 days in our hospital, he was able to fly home. It was a longer road for Cody. Thankfully, he survived surgery but faced paralysis from the waist down. The 37-year-old U.S. military veteran was in a coma for a week and remained in our care until mid-February, when he was stable enough to get a medical flight back home. He had a tough recovery, but he’s learned to walk again. The last time I spoke with him, he told me he’s now hiking.

“When you do hear ‘thank you’ from a patient or a family member, it’s humbling. It doesn’t make you walk prouder, it’s just humbling”

– Dr. Maher Matar

That was a successful day. It all started after midnight. All hands were on deck, including the highly-skilled Drs. Jetty and Rubens. We had never worked together before and those two collaborated on that case and saved the patient’s life. Also, there’s the exceptional anesthesia care provided by Dr. Adam Dryden – he worked with speed and efficiency to help save the patient. It was a team effort on many levels.

Humbling to hear the words “thank you”

And, when you hear ‘thank you’ from a patient or a family member, it’s humbling. It doesn’t make you walk prouder, it’s just humbling. There have been cases where I haven’t been able to save a life and that will always haunt me.

At the end of the day, when I walk out the hospital doors, the first thing I do is take a deep breath because the air is different outside. I just look up and I say ‘thank you’ for being able to deliver that specialized care.

Bret Howard says thank you for the compassionate, lifesaving care

“I truly don’t believe Cody would be alive today if he hadn’t been transferred to The Ottawa Hospital – that saved his life.

“Had we been somewhere other than The Ottawa Hospital, we think the outcome would have been worse, so we’re forever grateful.”

– Bret Howard

The way the team stepped in to get all of us together was a special thing to do and we won’t ever forget that – I actually don’t think that’s typical. I couldn’t have imagined going through all of this at one hospital while my brother fought for his life at The Ottawa Hospital. It meant a great deal to my family that we were all together.

Dr. Matar was incredible. Not only with my surgery but to my family – my wife and my parents. He and his team guided them along and was totally in tune with what was going on with me and my brother.

Thank you to the nurses, to the doctors, to the social workers. I could just tell they were invested in the situation with us and truly wanted to help guide us through it. Had we been somewhere other than The Ottawa Hospital, we think the outcome would have been worse, so we’re forever grateful.”

Research advancing trauma care

Research at The Ottawa Hospital is helping to improve survival and quality of life for people who experience severe traumatic injuries. Projects underway include:

- developing of a simple tool to help detect major bleeding in trauma patients, so that it can be treated earlier.

- testing new approaches to manage bleeding and blood clots in people with traumatic head injuries.

- developing of new rehabilitation technologies and prosthetics, including a brain computer interface that could help people control a robot arm just by thinking.

- developing a tool to help paramedics determine which trauma patients need to be immobilized on backboards, and which can be safely evaluated without immobilization.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.