Patients don’t need to have a metal halo screwed into their skull when they receive radiation treatment with the CyberKnife. That was one of the appealing factors for neurosurgeon Dr. John Sinclair to bring the radiosurgery robot to The Ottawa Hospital.

With other radiosurgery, patients with brain tumours had to have their head held perfectly still during treatment. A metal frame or “halo” was screwed into their skull and then fastened to the table they’d lie on for treatment.

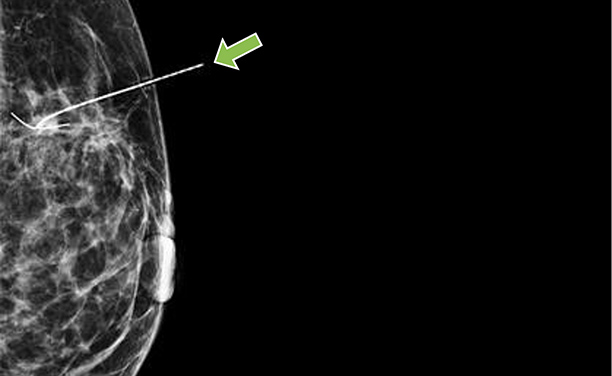

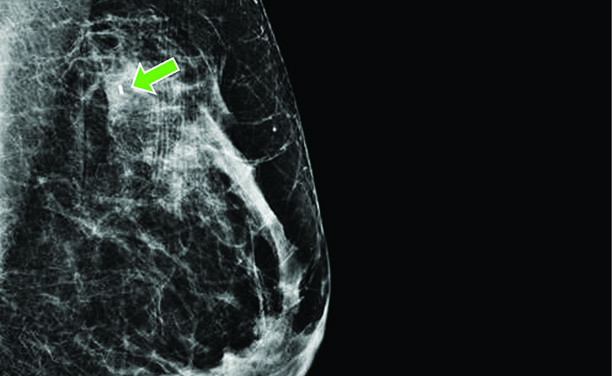

However, patients do not need to be held still when receiving CyberKnife radiosurgery. The robot uses x-rays and complex precision software to accurately track the tumour. It gives a high dose of radiation to the precise location of the brain tumour while the patient, who is fitted with a custom-made plastic mask, lies on the table.

“CyberKnife has an advantage over regular radiation because it is so much more accurate; its precision is less than a millimetre,” said Dr. Sinclair, Director of Cerebrovascular Surgery at The Ottawa Hospital. “You can give very high doses of radiation right to the lesion [tumour] and get almost no spill over to normal tissue. And as a result, we see greatly improved responses to this type of treatment compared to regular radiation.”

Dr. Sinclair was first introduced to the CyberKnife when he did a fellowship at Stanford Medical Center in California. CyberKnife was invented at Stanford, so the neurosurgeon was one of the first to see the benefits of this frameless radiosurgery treatment.

When Dr. Sinclair was recruited to The Ottawa Hospital in 2005, he had hoped to bring this novel technology to patients here. At the time, it was a technology that wasn’t approved by Health Canada. So, Dr. Sinclair and his team made a case for robotic radiosurgery, presenting scientific data that validated its success.

The Ottawa Hospital was eventually one of two health research centres in Ontario allowed to test the CyberKnife. However, there was no government funding available to purchase the machine. The hospital appealed to the community, which pulled together and generously donated the entire $4 million to purchase it. CyberKnife began treating patients at The Ottawa Hospital in September 2010.

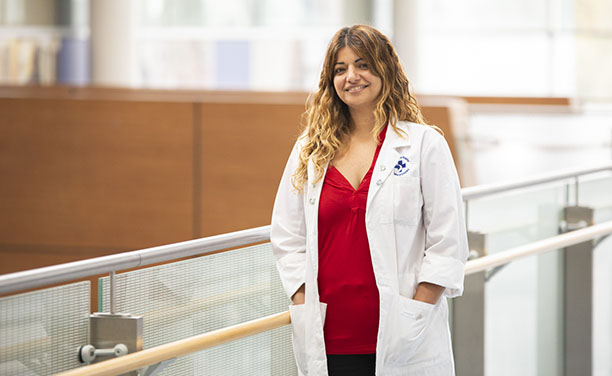

“Because it’s delivering a high dose, it’s considered similar to surgery without using a scalpel, so patients experience no blood loss, no pain, no ICU stay, or recovery time,” said Dr. Vimoj Nair, one of the radiation oncologists trained to prescribe CyberKnife treatment. “So CyberKnife radiosurgery does provide an option where people can be treated with outpatient techniques.”

With regular radiation, the daily doses were lower and patients had to come to the clinic for more radiation treatments overall. Regular radiation treatment could range from five to six weeks. With CyberKnife, radiation is focused precisely on the tumour, allowing larger doses to be given daily, therefore giving the total treatment in one to six days. The hospital’s CyberKnife has gained a reputation for improving treatment of various tumours. Dr. Nair said that because it is one of only three in Canada, patients from British Columbia to the Maritimes are occasionally referred to The Ottawa Hospital for treatment.

“At first, we would treat one tumour,” said Dr. Sinclair. “Now, we treat five or six individual tumours at a time and spare the rest of the brain. We’re sending radiation only to those metastatic tumours. There is a proportion of patients who develop cognitive problems a few months after whole-brain radiation. But with radiosurgery, because we give a higher dose of radiation only to the actual tumours, patients have improved outcomes, and so their quality of life is better.”

This has meant an increase in the number of patients having multiple tumours treated in the same session.

“Treating several tumours at once helps keep the patient’s clinic visits to a minimum,” said Radiation Therapist Julie Gratton, who has worked with CyberKnife since it was installed at The Ottawa Hospital. “Targeting individual tumours rather than treating the whole organ helps spare healthy tissues and reduce side effects.”

Until 2017, 1,825 patients had been treated with the CyberKnife. In 2018, 359 patients received 1,824 CyberKnife treatments. Gratton said that because more tumours are being treated at once in each patient, the number of treatments given per year has increased as expected.

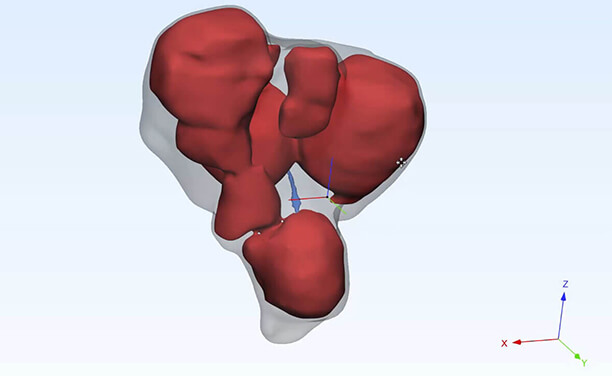

Although 90 percent of CyberKnife treatments are for malignant or benign brain tumours, CyberKnife is also being used to treat tumours in other parts of the body. Because it doesn’t require a frame to keep the area receiving radiation still, CyberKnife’s image guidance system is used to treat tumours in organs that move constantly, such as the lungs, kidneys, liver, prostate gland, and lymph nodes. CyberKnife can precisely align the radiation beam to the tumour even when it moves. The method of tracking tumours in organs and soft tissue has been improved by research at The Ottawa Hospital.

Read more about how our team is increasing the success rate of this already powerful and precise treatment.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.