OCTOBER 26, 2019 OTTAWA, ON – It was a sold-out night at The Ottawa Hospital Gala, presented by First Avenue Investment Counsel, which recognized three innovative researchers. The elegant ballroom of the Westin Hotel was transformed with exquisite décor and a delectable four-course meal, enjoyed by more than 700 guests. It also marked the final gala with Dr. Jack Kitts as President and CEO of The Ottawa Hospital, who will retire in 2020. Guests paid tribute to Dr. Kitts with a standing ovation for his dedication to providing compassionate and world-class care to the Ottawa community through his leadership since 2002.

The Ottawa Hospital Gala celebrated the transformational work of three researchers dedicated to improving care. Congratulations to this year’s three award winners:

Faizan Khan, recipient of the Worton Researcher in Training Award, recognized for his outstanding work on vein blood clots, including a recent British Medical Journal study establishing long-term risks and consequences of clot recurrence.

Dr. Marjorie Brand, recipient of the Chrétien Researcher of the Year Award, recognized for her groundbreaking discovery of how a blood stem cell decides whether to become a red blood cell or a platelet-forming cell.

Dr. Paul Albert, recipient of the Grimes Research Career Achievement Award, recognized for his leadership in Neuroscience, as well as his innovative work on what causes depression and how to treat it.

The Ottawa Hospital is recognized for its world-leading research that attracts internationally recognized scientists and clinicians from around the world. Tim Kluke, President and CEO of The Ottawa Hospital Foundation, emphasized that it’s corporate and individual philanthropic gifts, which make that a reality. “We are privileged to have the support of a generous community which is helping this city advance research to find new hope for patients now and in the future.”

First Avenue Investment Counsel returned as the presenting sponsor of The Ottawa Hospital Gala this year. Kash Pashootan, CEO and Chief Investment Officer at First Avenue Investment Counsel, said it’s a partnership that aligns perfectly. “Innovative research is a necessary investment in the future of health care in our community and we’re proud to fulfill our duty to The Ottawa Hospital. At First Avenue Investment Counsel, we advise families on all aspects of their financial picture including managing their assets to ensure their secure future for them and future generations. Together, we’re laying the building blocks for the future.”

About The Ottawa Hospital:

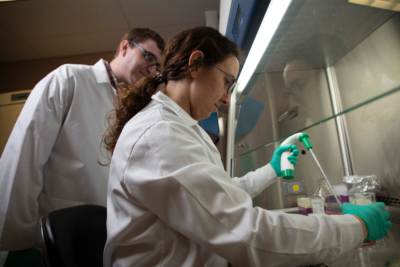

The Ottawa Hospital is one of Canada’s largest learning and research hospitals, with more than 1,200 beds, 12,000 staff members and an annual budget of about approximately $1.3 billion.

The focus on learning and research helps to develop new and innovative ways to treat patients and improve care. As a multi-campus hospital affiliated with the University of Ottawa, specialized care is delivered to the eastern Ontario region and the techniques and research discoveries are adopted around the world. The hospital engages the community at all levels to support our vision for better patient care.

From the compassion of our people to the relentless pursuit of new discoveries, The Ottawa Hospital never stops seeking solutions to the most complex patient-centred care. For more information about The Ottawa Hospital, visit ohfoundation.ca.