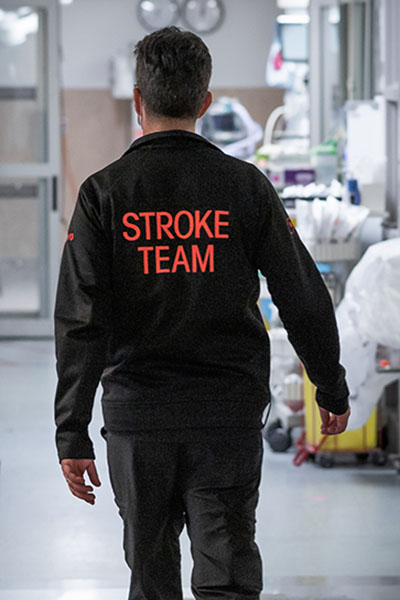

Dr. Alvin Tieu has been driven to make a difference for patients since the start of his academic career. From an early interest in the scientific method to a realization that research has a tangible impact on patients, Dr. Tieu’s journey has been shaped by how he can help others.

After an undergraduate and master’s degree at Western, Dr. Tieu came to uOttawa to pursue his MD/PhD and become a clinician scientist. Working under the supervision of Drs. Duncan Stewart and Manoj Lalu, his bench-to-bedside research could change the care of tomorrow.

In recognition of Dr. Tieu’s research, which takes laboratory discoveries one step closer to helping patients, he is the 2023 recipient of the Worton Researcher in Training Award.

Read on to learn what ignited Dr. Tieu’s interest in science and what exciting discoveries he’s working on today.

Q: Can you tell us a little bit about your early years?

A: I was born and raised in the Greater Toronto Area, in Scarborough. Both my parents were immigrants from Vietnam and worked multiple jobs to support our family growing up. Although they did not have a background in science or research, I can say for certain that my work ethic is a direct reflection of their daily commitment to ensuring I had the educational opportunities they never had.

I’ll be the first to admit that I wasn’t a great student when I was young. I was really into athletics, as I think a lot of kids are, and back then, if I’d really had to choose, I probably envisioned myself being an athlete. Luckily, my involvement in sports taught me how to work in teams and dedicate endless hours to activities I was passionate about. To this day, athletics still play a big role in my life.

Q: What made you choose to pursue a career in research and science?

A: I can still remember the exact time when I developed a love for science and research. Early on, I wasn’t interested in academics at all, but in Grade 7, I finally had a dedicated science teacher and course. Our first assignment was to write an essay on any topic we wanted, and for some reason, I chose the Big Bang Theory, about how the universe was formed. It was a big scope for a Grade 7 kid, but reading about it really sparked my interest. Learning that someone was able to conceive this complex theory with their own mind, math, and research was astonishing. That’s when I knew I wanted to incorporate science into my future career.

Q: How did you decide to study medicine specifically?

A: My bachelor’s and master’s were both in pharmacology. That’s when I began learning about the interesting physiology of the human body and disease. With pharmacology, you really have to know how drugs work to influence different body systems.

At that time, my affinity for research really grew. I was part of different labs and led a clinical trial during my master’s that investigated how to optimize the management of antihypertensive medications in patients on hemodialysis. These experiences inspired me to continue pursuing a career in scientific discovery with the goal of positively impacting the treatment of patients moving forward.

After this, I decided on the MD/PhD program at uOttawa — a seven-year program. When I was accepted, I remember my mom asking me, “Why are you in school for another seven years?” Although I had an appetite for research, I also developed an equal passion for medicine during my undergraduate studies. I had the opportunity to be a member of global health teams and saw how physicians can impact patients’ lives through active listening and patient-centred care. It inspired me to pursue a clinician-scientist career where I can both treat patients individually, face-to-face, but also conduct impactful research that can hopefully improve lives globally.

Q: What drew you to Ottawa for this phase of your career?

A: I heard great things about the medical school program in Ottawa, including their dedication to student wellbeing and clinical skills development. In terms of research, The Ottawa Hospital has one of the best research institutes in Canada. You have endless opportunities to be supervised under, or even collaborate with, scientists that are world leaders and experts in diverse disciplines.

Q: Can you describe your research?

A: I study extracellular vesicles, which are tiny particles naturally released by every single cell type in your body. Research in the past five to 10 years has shown that different cells communicate with each other through these little particles, thereby maintaining normal function in your body. However, they’re also involved in disease progression. For example, cancer cells can excrete these little particles as well, which may play a role in the development of disease locally and in other organ tissues.

I’m interested in isolating these extracellular vesicles from stem cells as an approach to treat lung diseases. Stem cells have been studied for decades now, and they show clear therapeutic potential in the lab. However, we have yet to translate that potential to patients. By isolating these little particles in high concentration, we can potentially harness the benefits of stem cells in a more practical way to treat devastating lung illnesses.

Q: How do you feel about winning the Worton Researcher in Training Award?

A: When I first heard that I was selected for the award, I was super excited because I know a lot of the previous recipients. Some of them were students, like me, and a lot of them I knew based off work they’ve done that really pushed the frontiers of scientific research. Being named alongside them is a great honour. Over half of my PhD was completed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which introduced a significant number of obstacles. All non-COVID research was halted for several weeks, and I had to completely alter my research objectives to include COVID-19 research. In the end, I was able to create what I think was an innovative, interdisciplinary thesis. I was thrilled to be this year’s award recipient and be recognized for my ability to adapt during these difficult times.

Q: Where would we find you when you’re not in the clinic or the lab?

A: Going to the gym is a way I relieve stress. As someone who played sports competitively growing up, playing volleyball or basketball with friends remains my main method of resetting my mind and maintaining wellness.

Other than that, I love to travel. Next year, I will be visiting Europe four times for vacations and weddings. Being able to be immersed in diverse cultures, tasting local delicacies, and summiting mountains in different parts of the world are experiences that can’t be beat!