Published: June 2025

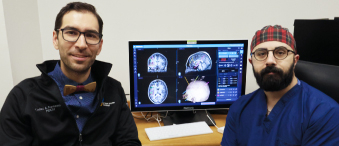

Between a quarter to a third of people having major liver surgery, often due to cancer, will need a blood transfusion. Now, imagine being able to reduce the need for this type of transfusion and the impact it would have on a global scale. This has been a vision for Dr. Guillaume Martel, a surgeon and scientist, who holds the donor-funded Arnie Vered Family Chair in Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Research at The Ottawa Hospital and University of Ottawa.

When Dr. Martel was training as a fellow in Montreal, he witnessed a technique for liver surgery that was new to him. It reduces the amount of blood loss during a liver operation, and the idea both fascinated and intrigued him. But when he did some digging, the young doctor realized there wasn’t much background on the technique and there were no clinical trials — no concrete evidence to prove its value.

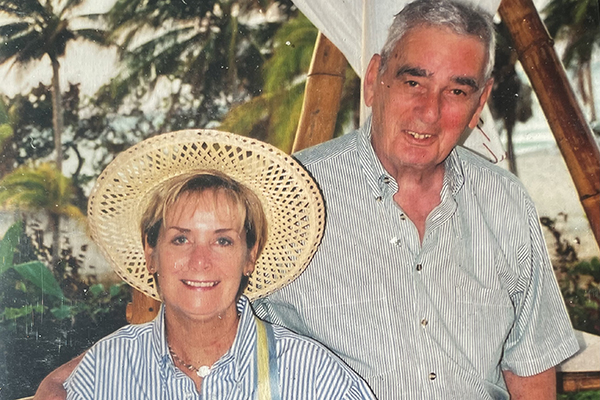

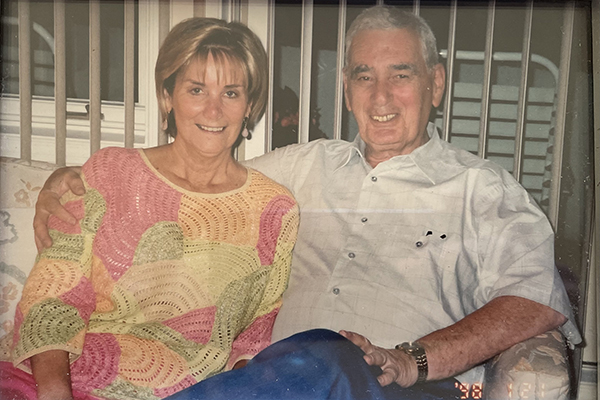

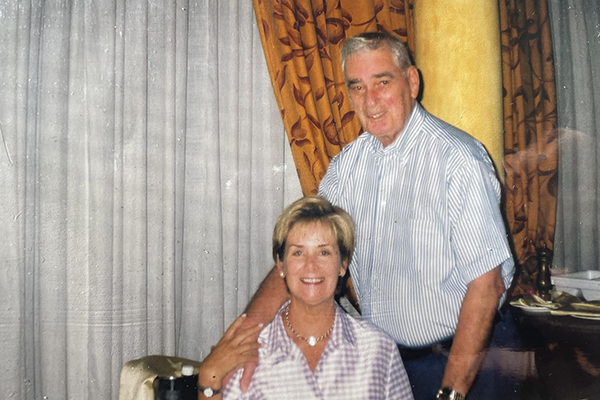

In August 2019, Dr. Guillaume Martel was announced as the first Arnie Vered Family Chair in Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Research. Dr. Martel is a gifted surgeon at The Ottawa Hospital who has saved and prolonged the lives of countless patients, particularly those with cancer. An international search conducted for this Research Chair found the best candidate right here in Ottawa. This Research Chair provides the opportunity for innovative clinical trials and cutting-edge surgical techniques that will benefit our patients for years to come. This was made possible through the generous support of the Vered Family, alongside other donors.

“When Arnie got sick, he needed to travel to Montreal for treatment. It was so hard for him to be away from home and our six children. We wanted to help make it possible for people to receive treatment right here in Ottawa. This Chair is an important part of his legacy.” – Liz Vered, donor

Launching the largest trial of its kind

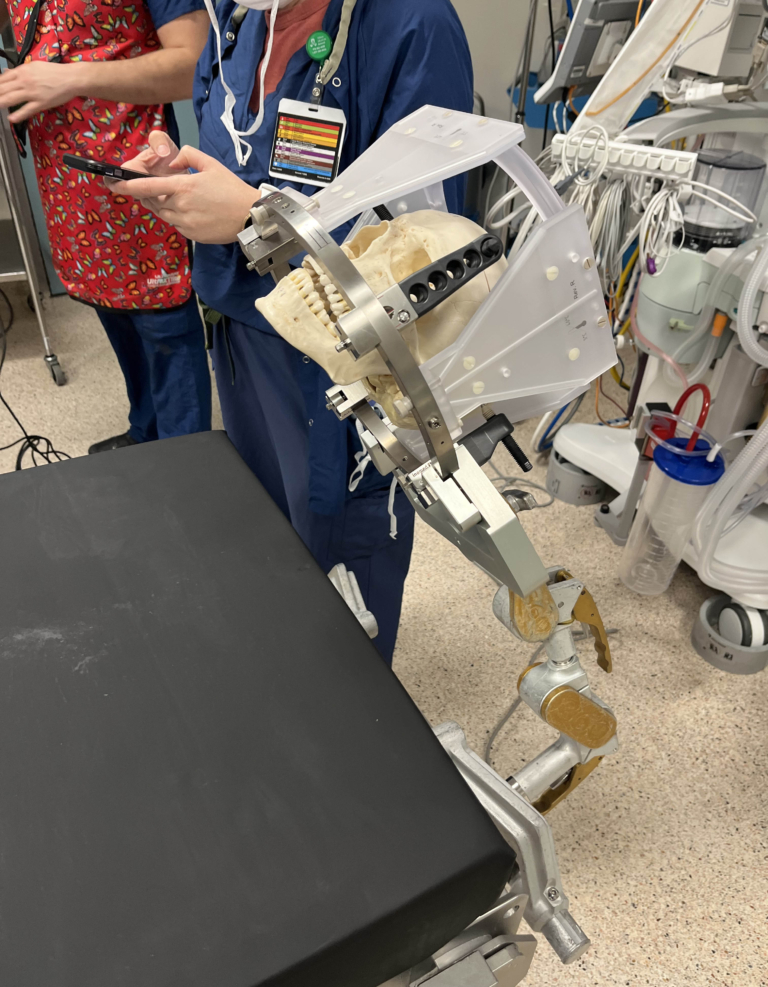

When he arrived at The Ottawa Hospital, it became a personal mission to learn more about the technique, known as hypovolemic phlebotomy, where a controlled amount of blood is removed from the patient before liver surgery, then reinfused back into the patient afterward. Once he and his team, including anesthetist Dr. Chris Wherrett, perfected the technique, they decided to do their own research, in order to have concrete evidence showing the impact of this practice-changing medicine.

Often, donations from the community help get the early phase research projects off the ground, attracting large-scale funding through grants to launch in-depth investigations. Once Dr. Martel’s team had tested the safety and feasibility of the technique in major liver surgery as part of a phase 1 trial at our hospital, they launched the largest trial of its kind, thanks to funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Over five years, ending in 2023, 446 people were recruited at four Canadian hospitals, including The Ottawa Hospital, to participate. “Once under anesthetic, patients were randomly selected to receive either hypovolemic phlebotomy, to decrease blood transfusions, or to receive usual care,” explains Dr. Martel.

Only the anesthesiologist knew which patients were in which group.

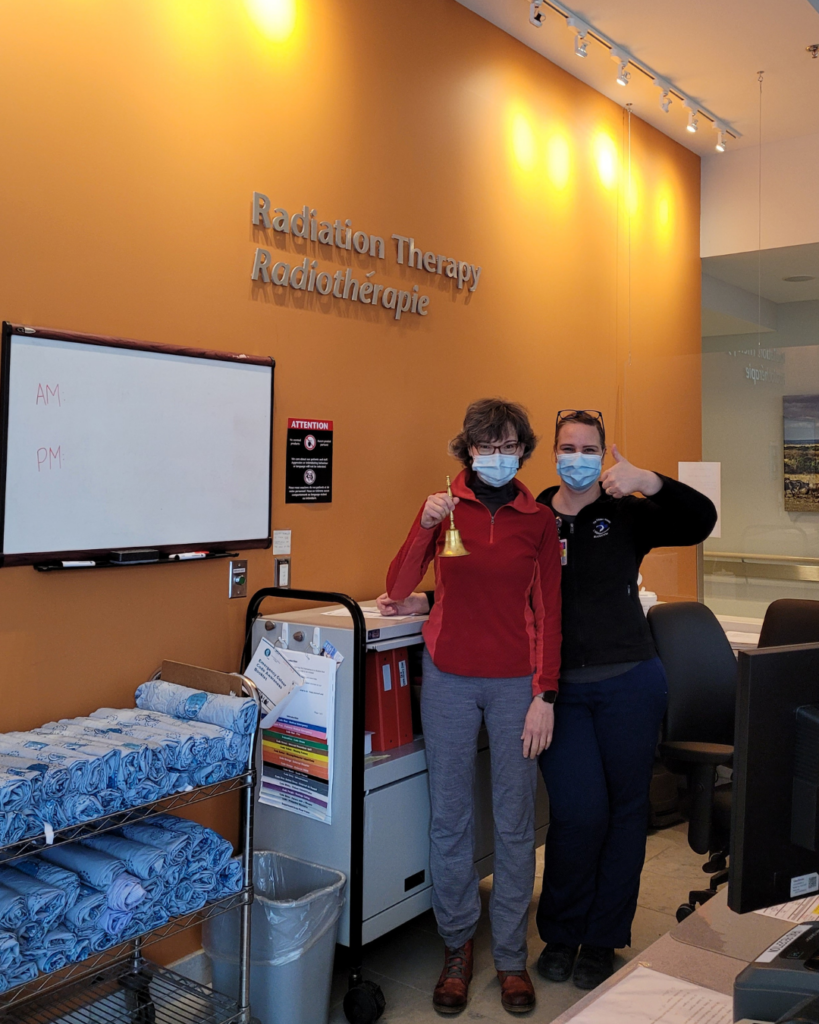

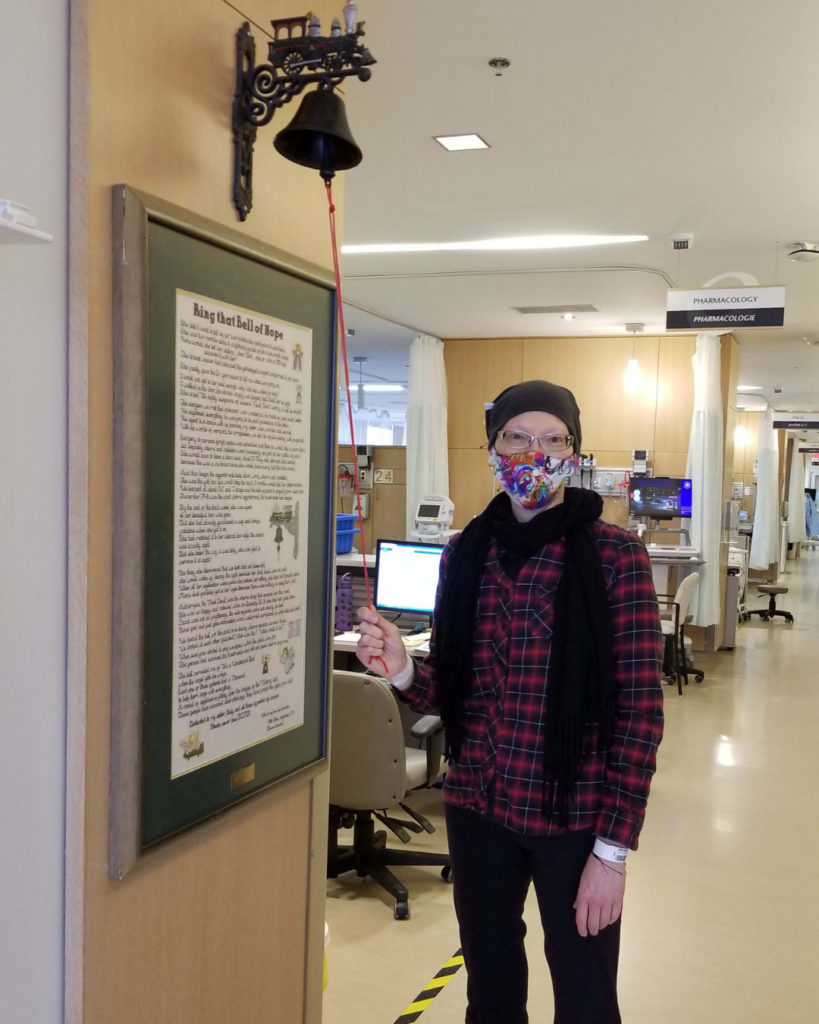

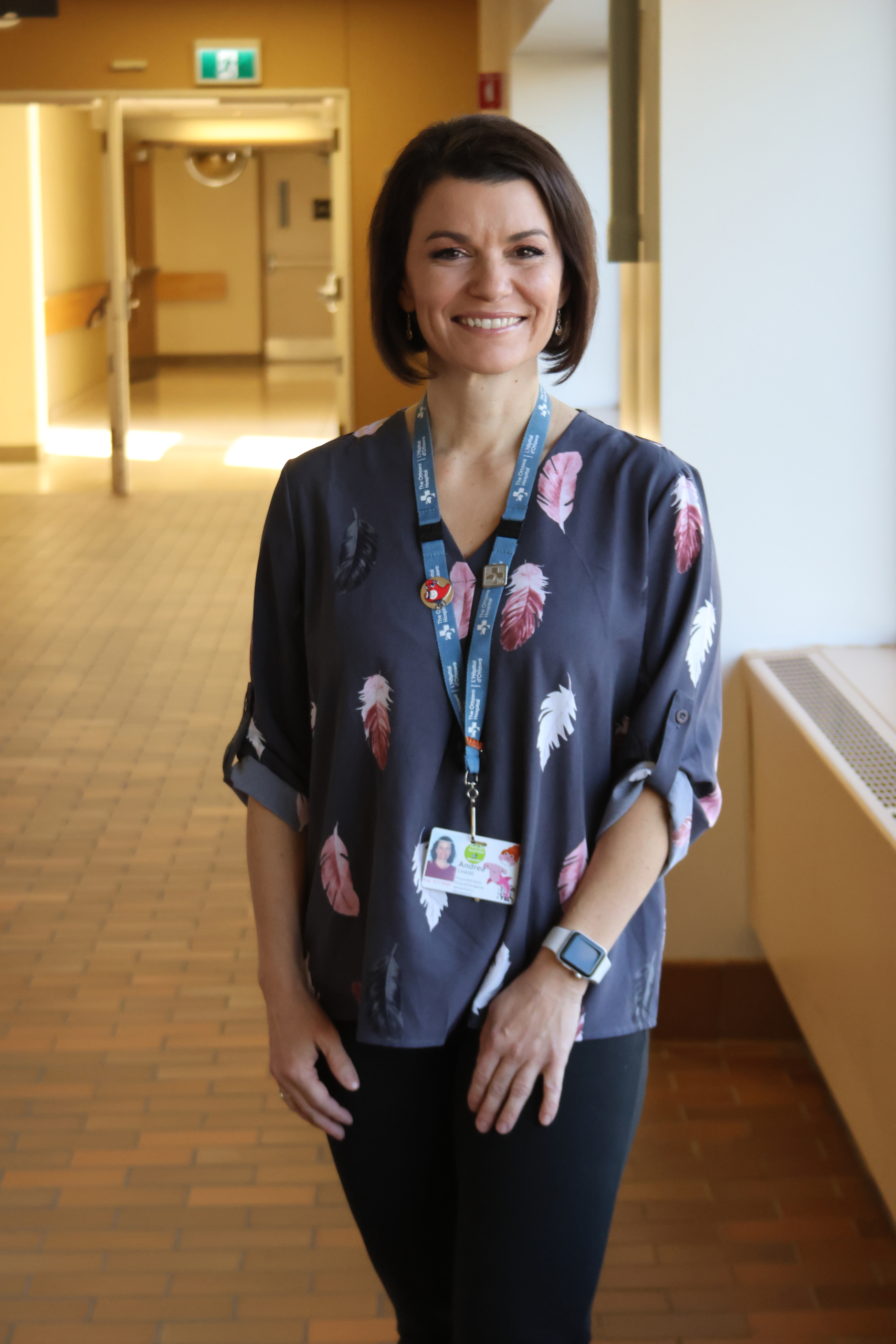

Raising her hand to participate in research

One of those patients enrolled was Rowan Ladd, a former analyst for the Department of National Defence, who was diagnosed with colon cancer in December 2020 at age 44.

“I was so scared and fearful — fearful that I was going to die.”

In the time leading up to her diagnosis, she recalls having many signs that she shrugged off as stress-related, so when the mother of two heard she had cancer, she was shocked. “I was so scared and fearful — fearful that I was going to die.”

Within three months of her diagnosis, she had a colectomy, a surgical procedure that removes all or part of the colon, and four months later she was back to work.

However, two years later, a regular MRI check showed a spot on her liver. Her cancer had spread, it was devastating news, and that’s when she met Dr. Martel. “You hear stage 4, and you think that’s it. But Dr. Martel explained that not every stage 4 means immediate death. He had patients he operated on who were alive years later,” says Rowan.

“I’m a big proponent of research. This study sounded interesting because they had great results in the pilot trial.”

When it came time to remove the tumour, Rowan didn’t hesitate to raise her hand to participate in the clinical trial. “I’m a big proponent of research. This study sounded interesting because they had great results in the pilot trial,” says Rowan. “You’re told before surgery that the liver is so full of blood vessels that there are risks of major bleeding. I thought it was great that researchers were trying things to reduce those risks.”

It was one thing to say yes to the trial, but Rowan was hopeful to be picked for the technique. Her surgery took place in October 2022, and later learned she was in fact randomly selected to have hypovolemic phlebotomy.

Reducing the risk of blood loss

For patients in the hypovolemic phlebotomy group, the anesthesiologist removed the equivalent of one blood donation (about 450 mL) into a blood bag before surgery. If the patient needed blood during surgery, their blood was used first. Otherwise, it was re-infused before they woke up.

“Blood loss is a major concern in liver surgery. Taking out half a litre of blood right before major liver surgery is the best thing we’ve found so far for reducing blood loss and transfusions,” says Dr. Martel. “It works by lowering the blood pressure in the liver. It’s safe, simple, inexpensive, and should be considered for any liver surgery with a high risk of bleeding.”

“Being part of this trial was a really positive experience, and the team was wonderful. I’m so glad I was picked, and I’m glad it will help other people.”

For Rowan, she was thrilled to be selected. She did not need a blood transfusion, and after four days in hospital, she was back home with her family in Dunrobin. Now, two years later she remains cancer-free.

“I looked at this surgery like it saved my life. I was unlucky to get cancer, but it woke me up. Now I live life, and I really enjoy it, where before I was just existing,” she says. “Being part of this trial was a really positive experience, and the team was wonderful. I’m so glad I was picked, and I’m glad it will help other people.”

The cost of saving blood for those who need it most

Liver surgery is considered a major operation. There is a higher-than-average risk of major bleeding and a consequence of that is the need for a blood transfusion during the operation to help keep the patient alive, help them recover, and thrive.

“Blood transfusions can save lives, but if you don’t need one to save your life then it’s better to avoid it,” says Dr. Dean Fergusson, senior author on the study and Deputy Scientific Director, Clinical Research at The Ottawa Hospital.

Meet Dr. Dean Fergusson

“There’s not an infinite amount of blood available in hospitals — it’s a precious resource.”

One blood transfusion in Canada costs about $500, mainly in human resources. The blood bags and tubes used for hypovolemic phlebotomy cost less than $30. As Dr. Martel points out, “There’s not an infinite amount of blood available in hospitals — it’s a precious resource.”

He also raises that blood collection has a considerable carbon emission. “We take it from donors and clinics, then we transport the blood. It needs to be processed and separated into components in a facility, then it needs to be stored. That all adds up to a pretty significant carbon footprint,” adds Dr. Martel.

What does this mean for patients?

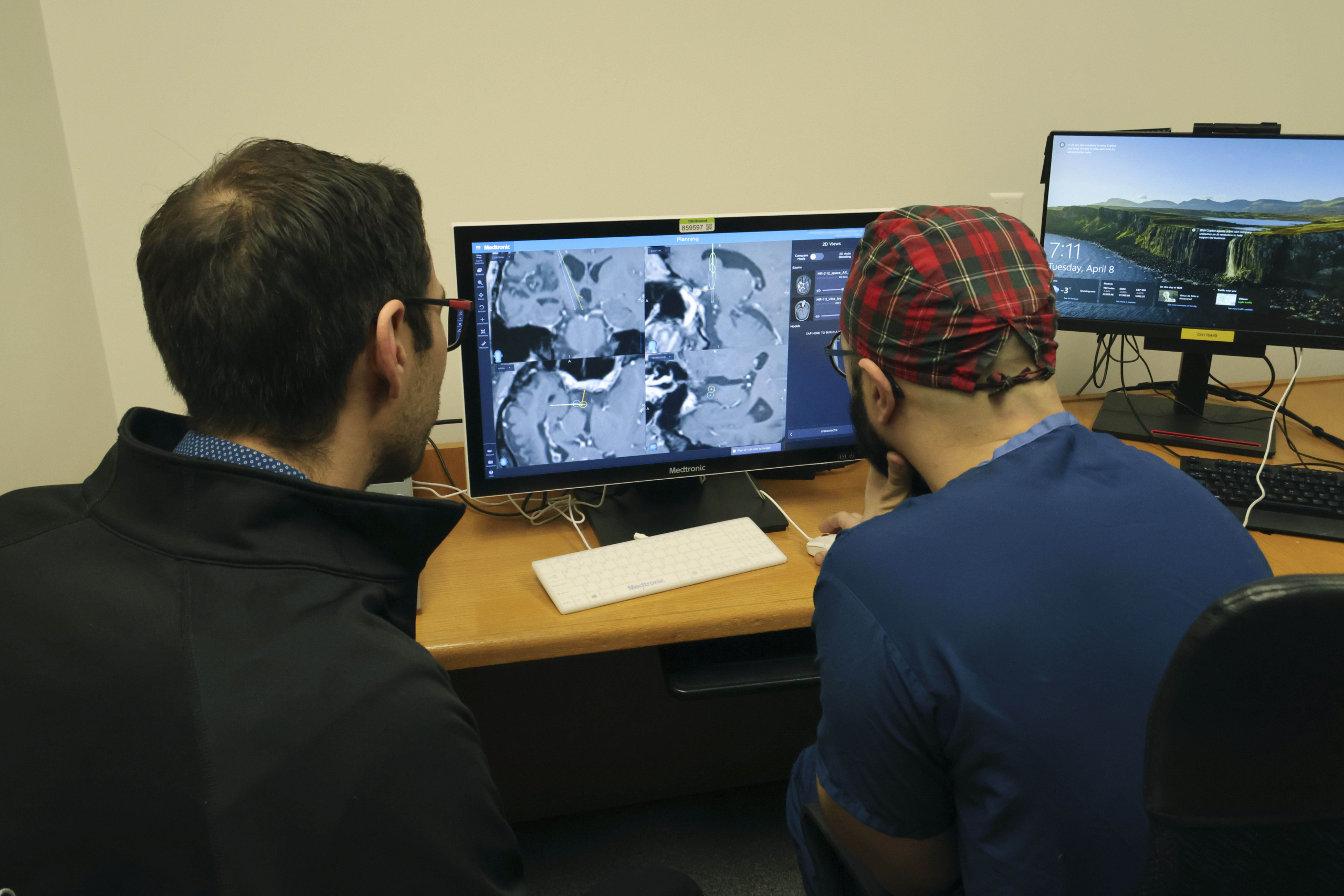

Hospital blood bank data and patient medical records show 7.6% of those who received hypovolemic phlebotomy had blood transfusions in the 30 days after surgery compared to 16.1% of those who received usual care. Hypovolemic phlebotomy caused no more complications than usual care.

“With this technique, your odds of requiring a blood transfusion drop by half, without any added risk to you. So, it's a win-win.”

Surgeons also say the technique made surgery easier because there was less blood obscuring the places they needed to cut.

According to Dr. Martel, this is a gamechanger for patients anywhere having major liver surgery. “With this technique, your odds of requiring a blood transfusion drop by half, without any added risk to you. So, it’s a win-win.”

Now the goal is to spread the word and educate surgeons around the world. The hospitals that participated in the trial, including The Ottawa Hospital, have implemented the technique as standard of care, and it’s believed other hospitals globally will start to adopt it when they learn about the transformational results.