Published: November 2024

The pace at which medical advancements are taking place in the field of immunotherapy is staggering. Immunotherapy harnesses a patient’s own immune system to attack their cancer, and The Ottawa Hospital is at the forefront of research in this area — from the development of new therapies to clinicals trials. In fact, our hospital hosts BioCanRx, a national network for immunotherapy research and has pioneered a number of unique immunotherapies made directly of cells and viruses. These groundbreaking immunotherapies, developed right here, are pushing the boundaries of medicine and transforming patient care.

“The field of oncology is like a hurricane of clinical trials. Every six months now, we are trying to implement practice-changing data or chase promising data.”

— Dr. Michael Ong

Unlike traditional treatments like chemotherapy, immunotherapy can adapt to a patient’s cancer, which can lead to improvements that can last years — even after the patient has stopped treatment.

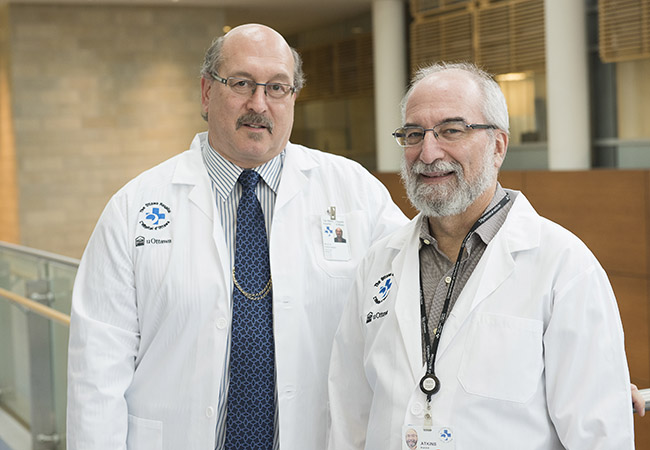

For Dr. Michael Ong, a medical oncologist and clinical investigator at The Ottawa Hospital, it’s reassuring to see the combination of incredible progress and long-term success for patients during his career. “The field of oncology is like a hurricane of clinical trials. Every six months now, we are trying to implement practice-changing data or chase promising data.”

The survival rates for metastatic melanoma, for example, have gone from only 20% surviving one year to 50% not only surviving 10 years, but also being both cancer-free and treatment-free. This is thanks to immunotherapy.

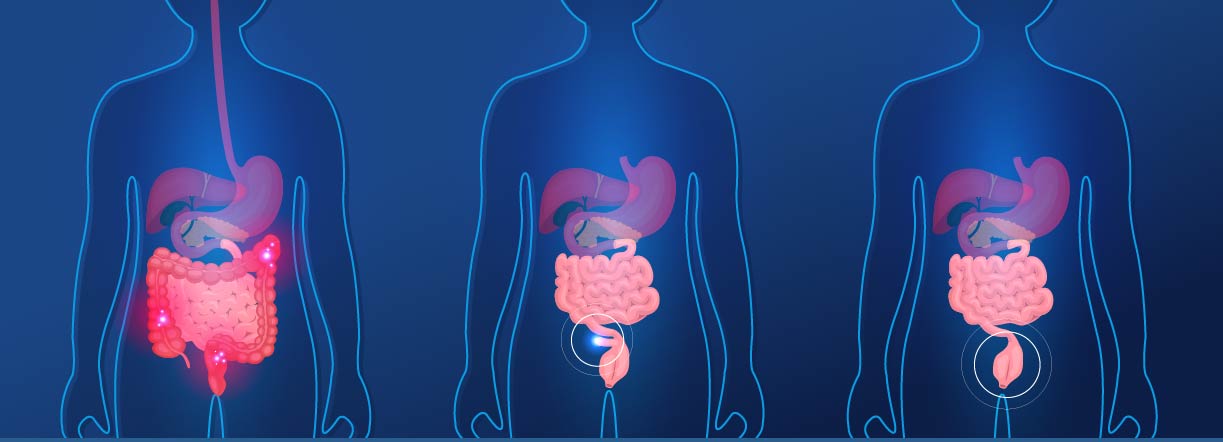

Immunotherapy shows promise for bladder cancers

Now, experts like Dr. Ong are asking what other cancers can be treated with immunotherapy and how to harness its full potential. “Over the years, we’ve been doing melanoma surgery for those who are high risk, and then treating with immunotherapy after surgery. But it turns out immunotherapy works better before surgery happens, because the immune system can be better trained against the cancer when there’s more cancer present,” explains Dr. Ong.

That means treating with immunotherapy first, and envisioning a future where surgery could one day be unnecessary. This would be a huge improvement for patients’ quality of life.

Recently, the results of a clinical trial led by Dr. Ong at The Ottawa Hospital as part of a multinational effort were presented at a conference in Barcelona, Spain. In this trial, chemotherapy and immunotherapy were prescribed before surgery in patients with bladder cancer. The group that had immunotherapy prior to surgery had a lower rate of cancer recurrence and higher cure rate, and it is now considered standard of care to offer pre-operative immunotherapy.

“It’s so exciting to have recruited patients to this trial and contributed to this global effort that ultimately improved how we treat our patients with bladder cancer,” explains Dr. Ong.

The next generation of trials may look at whether there is a need to remove a patient’s bladder if they are super responders. “Not everyone will get away without surgery, but even if some patients can avoid it, then it’s a huge advancement. We are talking about complete response rates from pre-operative treatment that are now exceeding 50% in bladder cancer,” says Dr. Ong. “So, by the time of surgery, we’re not even seeing any more cancer cells. That begs the question, ‘Do we need to take out the bladder’.”

The fact that each person’s cancer is unique adds to the complexity of the disease and treatment. But the potential impact of immunotherapy is reaching even farther.

What is prostate cancer?

How some prostate cancer patients may benefit

There have previously been significant efforts to evaluate if immunotherapy works in patients with prostate cancer. Multiple phase-three prostate cancer clinical trials have had largely disappointing results. However, within every one of these trials, there were a small proportion of patients who benefitted, and it shows that 3 out of 100 patients can actually benefit significantly from immunotherapy.

It has taken time and more data to understand who these patients were, but it has come down to something called mismatch repair deficiency, which seems to be the most promising way to identify patients that will respond to immunotherapy. “Normally when cancer cells copy their DNA, mistakes (or mismatches) in copying happen. The mismatch repair system will normally catch and fix those errors. But if this repair system is deficient or faulty, these mistakes are tolerated and DNA mutations accumulate rapidly,” says Dr. Ong.

Cancers generally become more aggressive when more mutations accumulate. “It turns out, however, that these ‘ugly’ mutated cancers are actually very sensitive to immunotherapy,” according to Dr. Ong.

That’s incredible news for a small but specific group of patients with prostate cancer, like Larry Trickey.

Stage 4 prostate cancer diagnosis

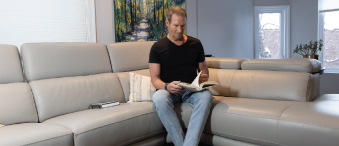

Larry Trickey, a retired computer specialist, was diagnosed with a highly aggressive prostate cancer in 2022. His scans showed the cancer had spread to the bladder and pelvis. It was the height of the pandemic, adding to the stress, and surgery was not possible. Initially, he began standard hormone treatment, then his oncologist, Dr. Dominick Bossé, suggested he enroll in a study that involved genomic testing of his tumour and access to a new treatment called a PARP inhibitor.

“When Mr. Trickey and his wife walked into my office with determination and hope, they were deeply supportive of one another and committed to finding the best path forward,” explains Dr. Bossé. “As always with research, the addition of a new form of care on top of standard treatment could make it more challenging to tolerate, but may also uncover new ways to treat cancer efficiently. Mr. Trickey was willing to take that risk.”

While initially Larry had benefit from the treatment, the effect was relatively short-lived, with the cancer worsening in 2023. He then received some radiation treatment and in a surprising turn of events, the radiation triggered an abscopal effect — a very rare phenomenon where the immune system kicks in to fight cancer after radiation releases.

“It was a remarkable moment. Mr. Trickey put his trust in me to hold off on further treatments while he benefited from this abscopal effect and until the cancer showed signs of progression, with the hope of enrolling him in an immunotherapy trial as our next option,” says Dr. Bossé.

“The entire team rallied together — the research team, radiology, oncology — to get him promptly into that trial."

— Dr. Dominick Bossé

Clinical trial led by Dr. Ong

Within months, Larry’s condition started to deteriorate and that’s when Dr. Bossé said it was time to see if he could enroll in a clinical trial that Dr. Ong was running. “The entire team rallied together — the research team, radiology, oncology — to get him promptly into that trial. Despite the alarming news of progression, Mr. Trickey agreed to multiple tests for the trial eligibility, which he met just in time, hours only before the trial closed.”

Larry remembers the call vividly. “It was around suppertime when Dr. Bossé called, and he seemed to be very ecstatic about one of the mutations I had,” remembers Larry. “There was a study looking for patients with that mutation. He was so excited when he saw the results and what it could mean for me.”

Hundreds of patients in Canada have been enrolled in this study over the last five years, but Larry was the last one accepted before the trial completed.

“It was kind of like winning the lottery to have that mutation. I was very lucky that it allowed me to get into this more aggressive study. If it was successful, it would really make a huge difference,” says Larry.

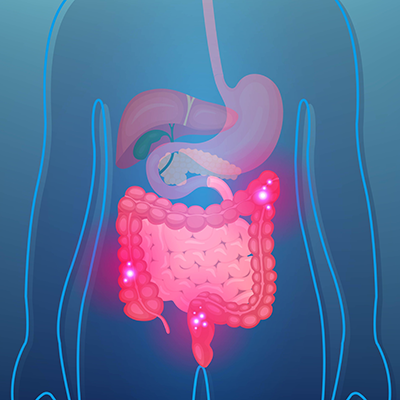

And Larry needed a win because by this time he had multiple metastases, including one in his left shoulder that was progressively weakening his arm. His stomach was bloated, and he was in pain because of the size of the tumour on his prostate and the difficulty of having bowel movements.

“Things were getting desperate for me. My son and his wife were expecting their first child around Christmas, and I didn’t know if I would ever get to meet my first grandchild.”

Astonishing results from immunotherapy clinical trial

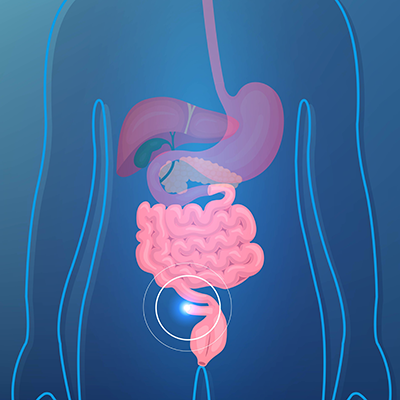

By mid-February 2024, Larry started on the PC-BETS study, with the Canadian Cancer Trials Group, for which Dr. Ong is a national co-chair. The results were astounding, and his condition improved very quickly after receiving two types of immunotherapies in combination.

"The cancer just melted away."

— Dr. Michael Ong

“The cancer just melted away. His PSA (prostate-specific antigen) in February 2024 before we started the trial was high. By April, his PSA was undetectable, and it’s stayed undetectable. The scans in July 2024 showed only a small residual nodule on the left adrenal gland. All the other sites of cancer have disappeared on his scans, and by the next scan, it’ll hopefully all be gone,” explains Dr. Ong.

To put this in perspective, a few cycles of chemotherapy would have maintained his life, but would not have improved it in the end. This clinical trial truly changed Larry’s life.

Read our Q&A with

Dr. Michael Ong

"If it wasn't for the trial, for sure, I don't think I'd be here now."

— Larry Trickey

Larry will continue with monthly immunotherapy treatment, but Dr. Ong says for how long is something that is also still being studied. “There’s an open question with immunotherapy right now to understand how long we need to deliver these treatments even when the scans normalize. That doesn’t mean every last cancer cell is gone. There are currently studies trying to address that.”

Today, the 69-year-old is enjoying every moment as a grandfather, and now he’s optimistic he’ll be able to celebrate that special milestone of his grandson’s first birthday. He’s also gaining his strength back, little by little, and he’s got movement back in his left arm. “If it wasn’t for the trial, for sure, I don’t think I’d be here now.”

He and his wife are deeply grateful to the cancer care team who have been with them every step of the way. “The nursing team honestly feels like family, especially Rayelle Richard, she’s really terrific. She gives me my infusions and is my contact to Dr. Bossé and Dr. Ong. It is such a supportive team at the Cancer Centre.”

What’s next in the field of immunotherapy?

For Dr. Ong, the goal is to find the right fit of treatment for each patient — it’s about individual analysis for each prostate cancer patient.

He also points to the importance of having access to things like The Ottawa Hospital’s molecular lab, funded by donors, which allows our scientists to do this kind of specialized testing and to provide much more personalization of care to patients. “We need to be at the forefront and test our patients for those mismatch repair alterations and get them immunotherapy when indicated,” says Dr. Ong. “That will be a significant advancement and will benefit more patients like Larry.”

Admittedly, the field is complex and moving at a rapid pace. Since he entered the medical oncology field 15 years ago, the change has been remarkable.

“I was a little bit concerned at that time that I would only ever be just delivering chemotherapy and never having a big impact. I was clearly wrong. Today, we’re seeing this totally new technology called antibody-drug conjugates that is revolutionizing bladder cancer treatment. They target the cancer specifically and then deliver high potency chemotherapy inside the cancer cells and that’s the huge advance of bladder cancer right now when combined with immunotherapy.”

Next is to bring this success to other patients with different types of cancers. The way to that will be through more cutting-edge research and clinical trials.

The Ottawa Hospital is also leading the way in research to develop and manufacture new cancer immunotherapies. For example, laboratory scientists like Drs. John Bell and Carolina Ilkow are developing biotherapies that use cells, genes and viruses to unleash an immune attack against cancer cells. They worked with clinician scientist Dr. Natasha Kekre and others to develop the first made-in-Canada CAR-T cell therapy. Other clinician researchers, like Dr. Alissa Visram and Dr. Rebecca Auer, are also developing new cancer immunotherapies and working to bring these to patients. This kind of research is fuelled by core facilities and platforms like The Ottawa Hospital’s Biotherapeutics Manufacturing Centre as well as networks like BioCanRx.