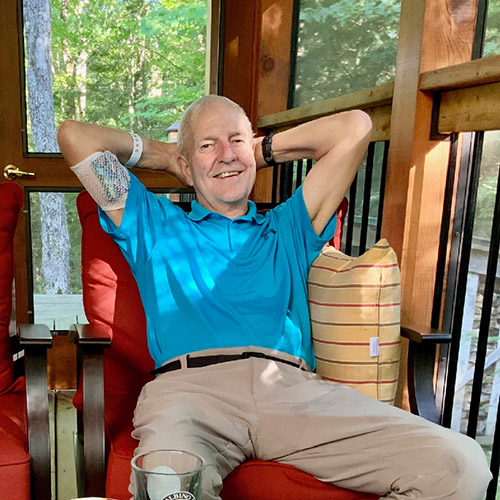

Vittorio Petrin has never seen his grandchildren’s faces. The Italian draftsman started to lose his peripheral vision in the early 1980’s after his second son was born, forcing him to leave work and take an early pension. He was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disorder that causes the cells in the retina to break down. There is no cure. His vision steadily got worse until he couldn’t see any light at all.

Before his vision went dark, Vittorio spent six years building a model of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, using over 3,000 copper pieces. “It was the most beautiful place I’d seen, and I wanted to replicate it. Working on it kept my mind away from what was going to happen,” he says.

“My dad was an artist. He was able to draw phenomenally, he liked taking videos. Sight was important to him,” says Vittorio’s son Dino Petrin. “He never complained about going blind, we never saw it as children. He always had a sense of humour and a strong character. He never asked for any pity, he just took it in stride.”

Millions of people in North America live with retinal diseases like retinitis pigmentosa, glaucoma, retinal ischemia and age-related macular degeneration. These diseases are poorly understood, progressive, and often untreatable.

But thanks to promising gene and cell therapies in development, Dino hopes that one day people like his father won’t have to lose their vision.

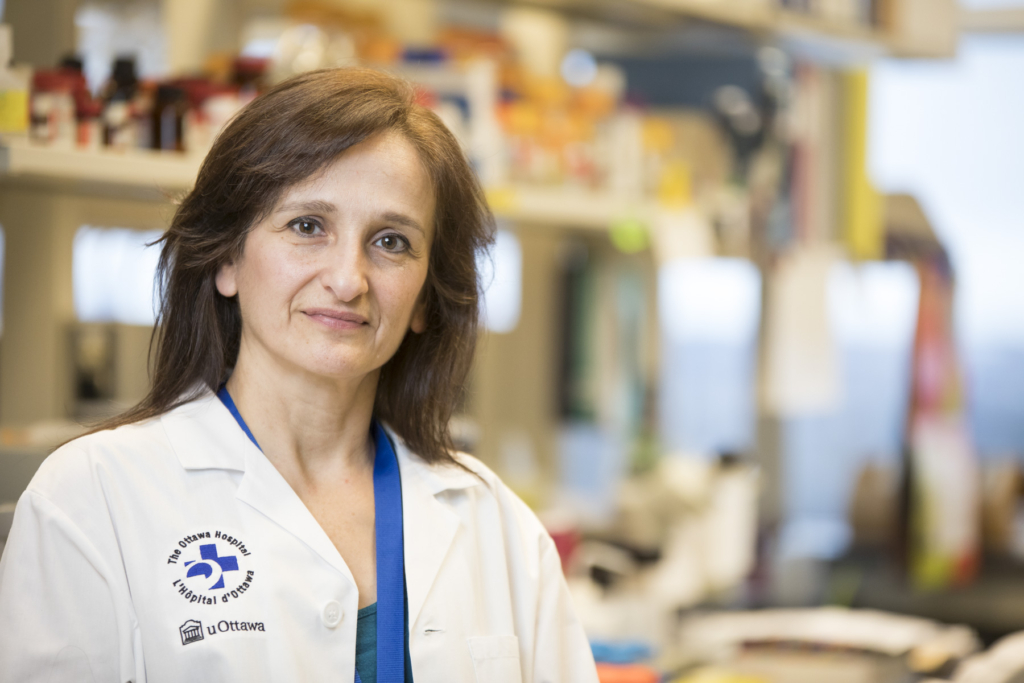

“Soon we’ll be able to do what our lab has been trying to do all along – bring XIAP gene therapy into the clinic.”

– Dr. Catherine Tsilfidis

A discovery with game-changing potential

Dr. Catherine Tsilfidis can imagine the day when the first patient is treated with the retinal disease gene therapy her lab has worked on for the past 20 years. While it won’t happen tomorrow, that day is not far off.

“XIAP gene therapy is exciting because it keeps cells in the back of the eye from dying,” said Dr. Tsilfidis, a senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital and associate professor at the University of Ottawa. “It could slow or stop vision loss caused by many different retinal diseases.”

Dr. Tsilfidis is leading a world-class team of researchers that recently received $2.4 M from the Ontario Research Fund to develop gene and cell therapies for retinal diseases. One of their goals is to do the work needed to bring XIAP gene therapy into clinical trials, which could start in the next few years.

The time is right for gene and cell therapy

The promise of replacing defective genes and cells in the eye with healthy ones is undeniable. While these fields are still in their infancy, they are expected to grow exponentially over the next decade. Gene therapy for the eyes has particularly taken off, with Health Canada approval of the first gene therapy for a rare genetic form of vision loss in 2020.

“This research program could make Ontario a leader in the fields of both gene and stem cell therapy

– Dr. Pierre Mattar

When it comes to cell therapies, Ottawa and Toronto are major hubs in the growing area of stem cell research. As partners in the retinal research program led by Dr. Tsilfidis, UHN scientist Dr. Valerie Wallace will work on increasing the survival of transplanted stem cells in the eye, while The Ottawa Hospital’s Dr. Pierre Mattar aims to develop stem cell therapies for retinal ganglion cell diseases such as glaucoma. “This research program could make Ontario a leader in the fields of both gene and stem cell therapy,” said Dr. Mattar. “By learning the best way to mass produce and integrate stem cells for retinal disease, we can advance stem cell research in other fields.”

Collaboration between lab researchers and clinicians key to success

The incredible challenge of bringing a basic science discovery to clinical trials requires an exceptional team. For this research program, Dr. Tsilfidis assembled a “dream team” of long-time collaborators and new partners.

As a basic scientist, Dr. Tsilfidis has always worked closely with clinicians to help ensure her research reflects patient needs.

“Ophthalmologists help us identify the most important questions to ask,” said Dr. Tsilfidis. “Our lab started working on diseases like Leber hereditary optic neuropathy and glaucoma because clinicians told us how much of a problem they were.”

Two of Dr. Tsilfidis’ long-time clinical collaborators, Drs. Stuart Coupland and Brian Leonard, are part of this new retinal research program. They are joined by retina specialists Drs. Bernard Hurley and Michael Dollin, who will assist in developing clinical trial protocols.

“Our researchers have an incredible track record of taking discoveries from the lab to the bedside,”

– Dr. Duncan Stewart

Dr. Tsilfidis’ lab and office are just down the hall from the ophthalmologists’ offices and clinics, which makes collaboration easier. This kind of co-location of scientists and clinicians has been key to The Ottawa Hospital’s success in translating discoveries from the lab bench to the patient bedside.

Leveraging our biomanufacturing expertise at The Ottawa Hospital

In addition to clinical experts, the team knew they needed new resources and partners to be successful.

“We’ve been very much a basic science lab in the past,” said Dr. Tsilfidis. “Now that we’re at the stage that we want to get XIAP to the clinic, we need all the help we can get.”

One missing piece was a special clinical-grade virus used to deliver the XIAP gene into the eye, known as an adeno-associated virus (AAV). Finding cost-effective sources of AAVs has been a major bottleneck for getting gene therapy trials and treatments off the ground.

Thankfully, The Ottawa Hospital is home to the Biotherapeutics Manufacturing Centre (BMC), a world-class facility that has manufactured more than a dozen different virus- and cell-based products for human clinical trials on four continents. Experts at the BMC were already starting to expand into AAV manufacturing when Dr. Tsilfidis approached them about collaborating on the retinal research program.

The BMC has since been working with Dr. Tsilfidis and her team to develop a process to manufacture the AAVs the team will need for Health Canada approval of the XIAP gene therapy for clinical trials.

The BMC is on track to become the first facility in in Canada to make clinical-grade AAV vectors for gene therapy studies. This new expertise will help them support other gene therapy trials with a focus on rare disease.

How to plan a world-class clinical trial

In addition to the clinical-grade virus, the retinal research team needed help planning a future clinical trial of XIAP gene therapy. Fortunately, there are no shortage of clinical trial experts at The Ottawa Hospital.

“I’ve never planned a clinical trial before,” said Dr. Tsilfidis “But I knew someone who had – Dr. Dean Fergusson. I’ve always been impressed by the rigorous trails he’s helped develop. When I asked for his advice, he referred me to the Ottawa Methods Centre.”

The Ottawa Methods Centre is The Ottawa Hospital’s one-stop shop for research expertise and support. Their goal is to help all clinicians, staff and researchers at the hospital conduct the highest quality research, using the best methods. They support over 200 research projects a year, led by clinical and basic researchers alike.

“The Ottawa Methods Centre has been amazing to work with,” said Dr. Tsilfidis. “Their research methodology expertise has strengthened this research program and our funding applications.”

At the Ottawa Methods Centre, the team is leveraging the Blueprint Translational Research Group’s Excelerator program, designed to enable efficient translation of basic research discoveries to the clinic through rigorous methods and approaches. Co-led by Dr. Dean Fergusson and Dr. Manoj Lalu, the program will help design the clinical trial protocol, and support the clinical trial application to Health Canada through systematic reviews of available pre-clinical and clinical data.

Research program holds enormous promise

Tackling retinal disease will be a big challenge, but Dr. Tsilfidis has assembled an excellent team of partners both old and new to move this research program forward.

“These therapies could be life-changing. If we could cure or slow down the progression of vision loss, that would be amazing.”

– Dino Petrin

“Our researchers have an incredible track record of taking discoveries from the lab to the bedside, but it can only be done through team efforts like this one,” said Dr. Duncan Stewart, Executive Vice-President of Research at The Ottawa Hospital and professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa. “Fully leveraging our basic and clinical expertise, as well as our world-class core research resources is the key to getting new treatments to the patients who need them.”

For Dr. Tsilfidis, the excitement is palpable. “Soon we’ll be able to do what our lab has been trying to do all along – bring XIAP gene therapy into the clinic.”

Dino, a former graduate student in Dr. Tsilfidis’ lab, sees the potential of gene therapies to help people like his father. “These therapies could be life-changing,” he said, “If we could cure or slow down the progression of vision loss, that would be amazing.”

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.