Making world-first discoveries and pushing the boundaries of breast cancer care and research right here at The Ottawa Hospital

In front of a buzzing crowd of more than 200 generous contributors and tireless allies, the new Rose Ages Breast Health Centre at The Ottawa Hospital officially opened its doors on September 20, 2018. The event marked a thrilling close to an ambitious $14 million fundraising campaign.

Built and equipped through the unfailing generosity of our community, the Centre now houses an impressive suite of technologies that are among the latest and most comprehensive in Canada. Many of them enable more accurate and much less invasive diagnoses and treatments.

But more than just technology, the new Centre was designed as an inviting space to enhance wellness and connection to friends and family. It also allows patients to be closer to the specialists involved in their care, from before diagnosis to after treatment, and beyond. This means, thanks to donor support, more patients can be treated with therapies that are tailored to their unique circumstance.

A comprehensive breast health program to address growing need

The Ottawa Hospital offers a comprehensive breast centre, providing expertise in breast imaging, diagnosis, risk assessment, surgical planning, and psychosocial support.

The consolidation of four breast health centres spread out across the city down to two (the Rose Ages Breast Health Centre and Hampton Park), allow for more centralized services, less travel time, improved patient care and operational efficiencies.

This year alone, another 1,000 women in our region will be diagnosed with breast cancer. Thanks to the generous donor community in the Ottawa region, The Ottawa Hospital is already tackling this growing challenge and working hard to improve every aspect of breast cancer care with innovative research and the very best treatments and techniques.

“Your generosity has improved the largest breast centre in Canada,” said Dr. Seely. “We are now poised to lead the way for excellence in breast health care.”

The creation of REaCT

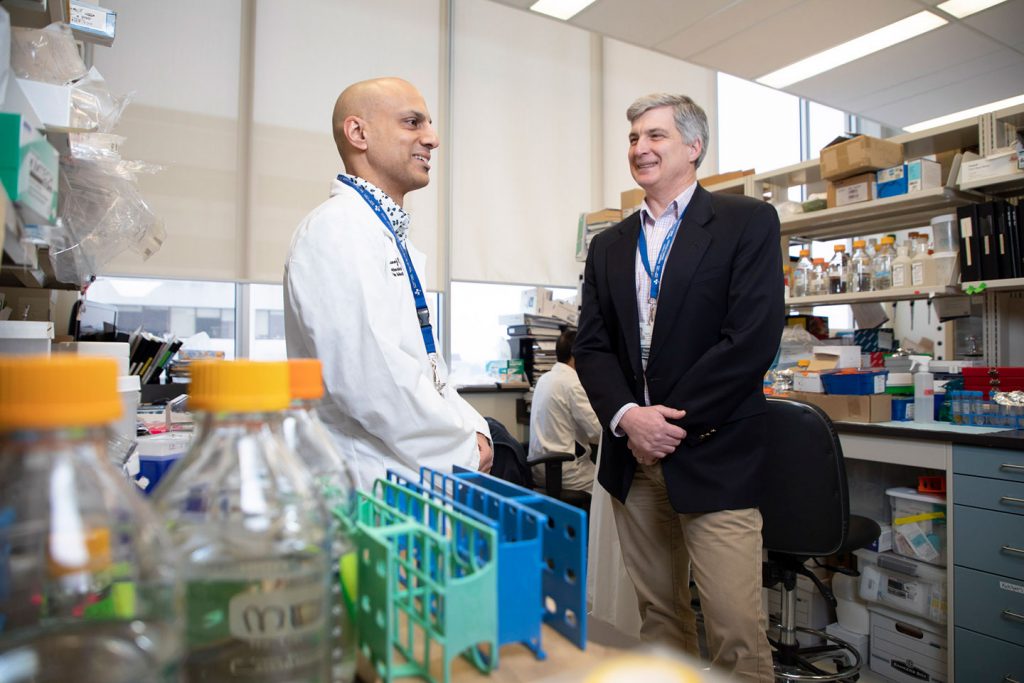

The Ottawa Hospital’s commitment to innovation and research is revolutionizing clinical trials, improving patient outcomes every day. Though clinical trials offer improved treatment options, less than three percent of cancer patients in Canada are enrolled in clinical trials. Part of the reason for low enrollment is the daunting prospect of lengthy paperwork each patient must fill out before becoming involved in a trial. As well, regulatory hurdles often make opening a new trial too expensive and time consuming. In response to these challenges, in 2014, Dr. Marc Clemons, medical oncologist and scientist, in collaboration with Dr. Dean Fergusson, Director of the Clinical Epidemiology Program, and their colleagues at The Ottawa Hospital, developed the Rethinking Clinical Trials or REaCT program as a way to make the process of enrollment in clinical trials easier and more efficient for cancer patients.

This ground-breaking program conducts practical patient-focused research to ensure patients receive optimal, safe and cost-effective treatments. Since REaCT isn’t investigating a new drug or a new therapy, but rather looks at the effectiveness of an existing therapy, regulatory hurdles are not an issue and patients can consent verbally to begin treatment immediately. By the end of 2017, this program enrolled more breast cancer patients in clinical trials than all other trials in Canada combined. Currently, there are more than 2,300 participants involved in various REaCT trials.

The Rose Ages Breast Health Centre 2018-2019 stats and facts

- 49,288 diagnostic breast examinations and procedures

- 2,397 breast biopsies

- 5,129 breast clinic patient visits

- 1,929 referrals to the Breast Clinic

- 889 diagnosed breast cancer patients

Specialized patient care

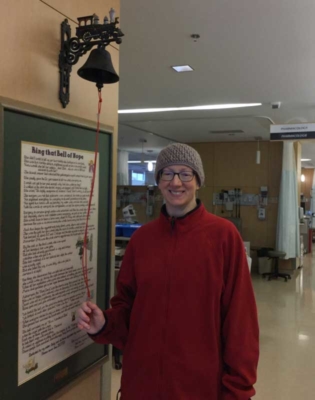

Tanya O’Brien

Five years ago, Tanya O’Brien received the news she had been afraid of all her life. Like her six family members before her, she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Today, Tanya is cancer-free. When she thinks back to the 16 months of treatment she received at the Rose Ages Breast Health Center at The Ottawa Hospital, Tanya credits her dedicated and skilled care team for guiding her through and out of the darkest time in her life.

“We have come so far as a community in changing the narrative of breast cancer. We have given women like me, like us, so much hope,” said Tanya.

Rita Nattkemper

When a routine mammogram identified a small tumour, Rita Nattkemper was given an innovative option to mark its location for the surgery. A radioactive seed, the size of a pinhead, was injected directly into the tumour in her breast.

For years, an uncomfortable wire was inserted into a woman’s breast before surgery to pinpoint the cancer tumour. Today, a tiny radioactive seed is implanted instead, making it easier for surgeons to find and fully remove the cancer, and more comfortable for patients like Rita.

“It’s a painless procedure to get this radioactive seed in, and it helps the doctor with accuracy,” said Rita.

Breast Health Centre Update 2018-2019

More inspiring stories

Annette Gibbons

‘I walked through my darkest fears and came out the other side.’

It would be a routine mammogram, which would turn Annette Gibbons’ world upside down. The public servant would soon begin her breast cancer journey, but she put her complete trust in her medical team at The Ottawa Hospital.

Vesna Zic-Côté

The gift of time with family

Mom of three, Vesna, is living with terminal metastatic breast cancer. She is hoping clinical trials will continue to extend her life so she has more time with those she loves.

International research to find breast cancer sooner

The Ottawa Hospital is one of six sites in Canada participating in the Tomosynthesis Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST), a randomized breast cancer screening trial that will help researchers determine the best ways to find breast cancer in women who have no symptoms, and whether a newer 3D imaging technique decreases the rate of advanced breast cancers.

The trial compares standard digital mammography (2D) with a newer technology called tomosynthesis mammography (3D). Conventional 2D mammography creates a flat image from pictures taken from two sides of the breast. With 3D mammography a 3D image is created from images taken at different angles around the breast.

Worldwide the study is expected to enroll around 165,000 patients over five years. With the new, increased mammography capacity at the Rose Ages Breast Health Centre we expect to enroll at least 1500 patients from our region.

Your impact

The Rose Ages Breast Health Centre at The Ottawa Hospital is committed to providing an exceptional level of care for patients, approaching each case with medical excellence, practice, and compassion. The Centre’s reputation for world-leading research and patient care attracts to Ottawa some of the brightest and most capable health-care professionals in the world who help deliver extraordinary care to patients in our community.

You continue to be a critical part of our success as we strive to redraw the boundaries of breast health care. On behalf of the thousands of patients and families who need The Ottawa Hospital, we thank you for your tremendous support and for your continued involvement.

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.