Published: January 2026

Read time: 3 mins

Published: January 2026

Read time: 3 mins

On a warm spring day in 2022, Jean Lebel set out for what was meant to be a routine bike ride through Cantley, Quebec, with his wife Anne-Marie and close friends. An experienced rider, Jean had travelled those winding country roads countless times before. But at one sharp hairpin turn, the ride quickly turned into every cyclist’s worst nightmare. A car suddenly appeared in front of him, and the head-on collision that followed left Jean unconscious, severely injured, and battling life-threatening injuries.

Love at first pedal

Cycling wasn’t just a hobby for Jean. Balancing a prestigious career as President and CEO of the International Development Research Centre, it was a way to escape the pressures of daily life and most importantly, connect with Anne-Marie.

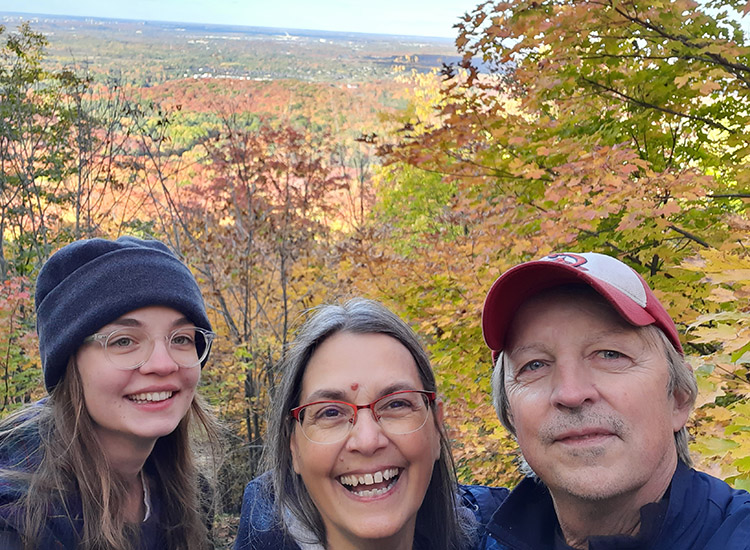

Their love story began on bicycles when Anne-Marie first cycled past Jean when she was 14 and he was 12. That moment sparked a connection that would resurface years later when they met again as young adults. Since then, they’ve built a life centred on adventure, family, and a shared passion for cycling around the world.

Never once did they imagine the same passion that brought them together would one day threaten to pull them apart, when Jean was in a crash that could have cost him his life.

From passion to peril

When he regained consciousness after the crash, Jean was disoriented. Though he recognized Anne-Marie’s face, he repeatedly asked the same questions — a sign of the severity of the impact. His shoulder struck the car’s side mirror, and his head hit the back-seat window before he was thrown off his bicycle onto the pavement. Anne-Marie watched helplessly as he drifted in and out of consciousness, fearing she might lose the man she loved.

“We have spent many years riding together,” says Anne-Marie. “Nothing can prepare you for a moment like that.”

Paramedics acted quickly and transported him to the Hull Hospital. The medical team immediately recognized that due to the extent of his injuries, Jean needed the highest level of trauma care available. He needed The Ottawa Hospital — the most advanced trauma centre in our region.

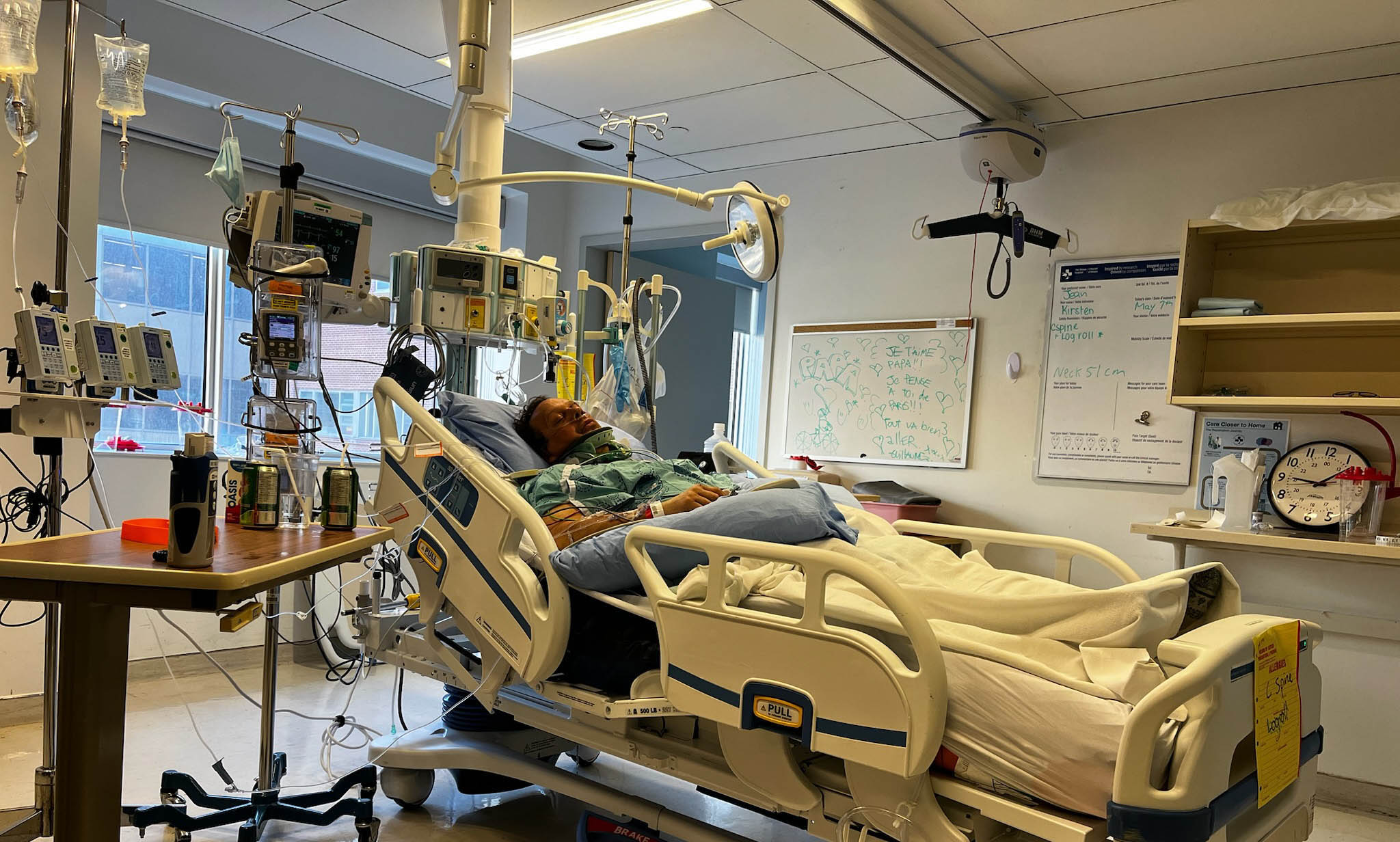

Jean woke in the hospital with no memory of the accident, but thankfully, he was in the hands of a world-leading trauma team who provided lifesaving care when he needed it most.

World-class trauma care

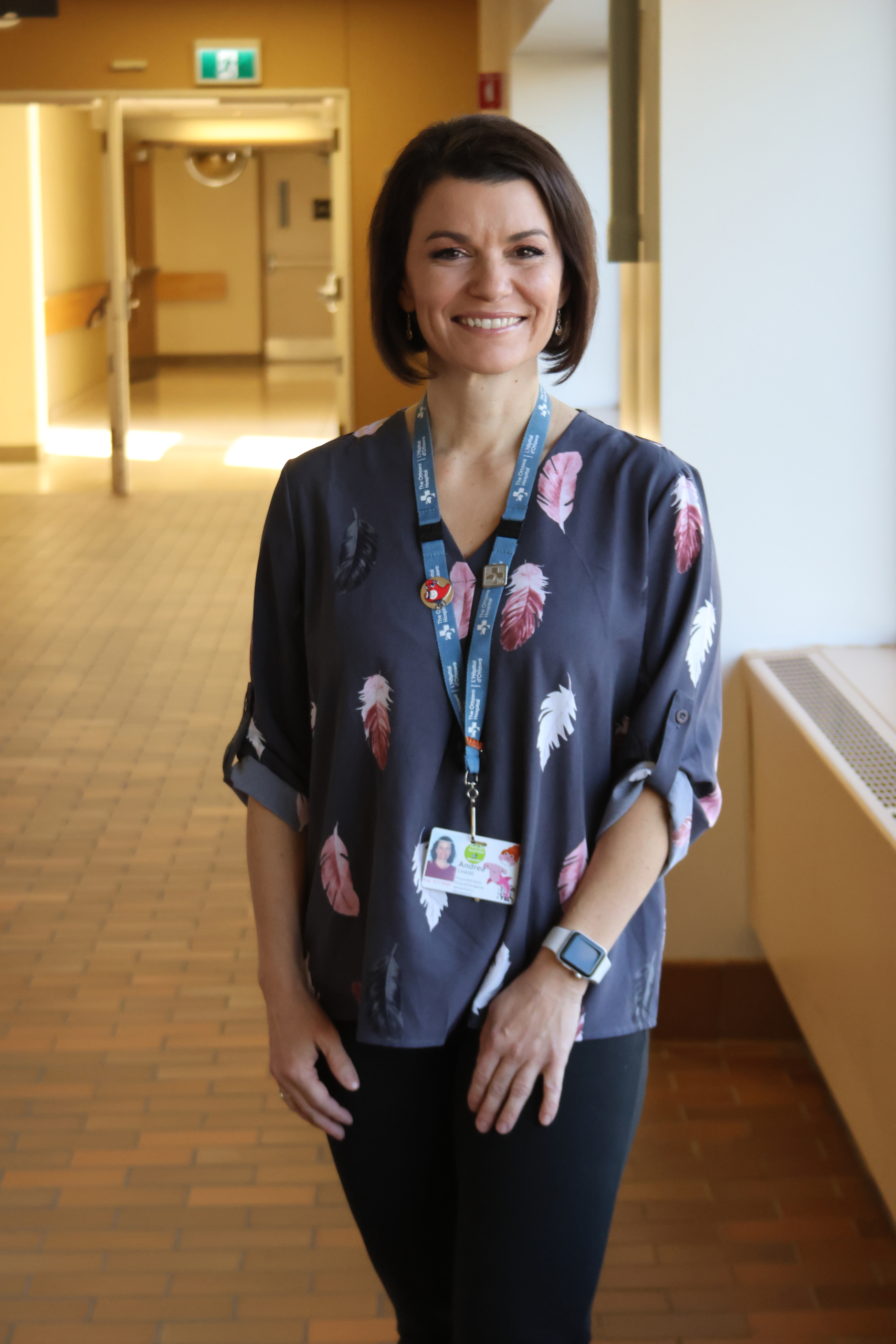

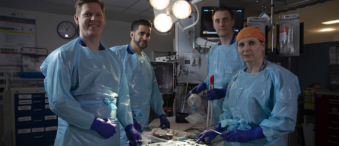

At The Ottawa Hospital, a multidisciplinary team was ready. Highly trained specialists from neurosurgery, orthopaedics, and critical care worked together in a swift, coordinated effort rarely seen outside a major trauma centre.

Jean’s injuries were extensive, including a dangerous C2 fracture at the base of his skull; a second spine fracture of his C6/T1; multiple broken ribs; shattered bones in his collarbone, shoulder and arm; a lung contusion; and a kidney laceration.

“People rarely survive a fracture like this. Jean was extremely lucky.”

— Dr. Safraz Mohammed

The C2 fracture was the most concerning — fractures here are often fatal. “People rarely survive a fracture like this. Jean was extremely lucky,” explains Dr. Safraz Mohammed, Staff Neurosurgeon at The Ottawa Hospital and one of the physicians overseeing Jean’s care. A fragment of bone had sheared off his C2 vertebra, pressing into the canal surrounding his vertebral artery. If it shifted even half a centimetre, it could sever the artery, causing a massive stroke — or worse.

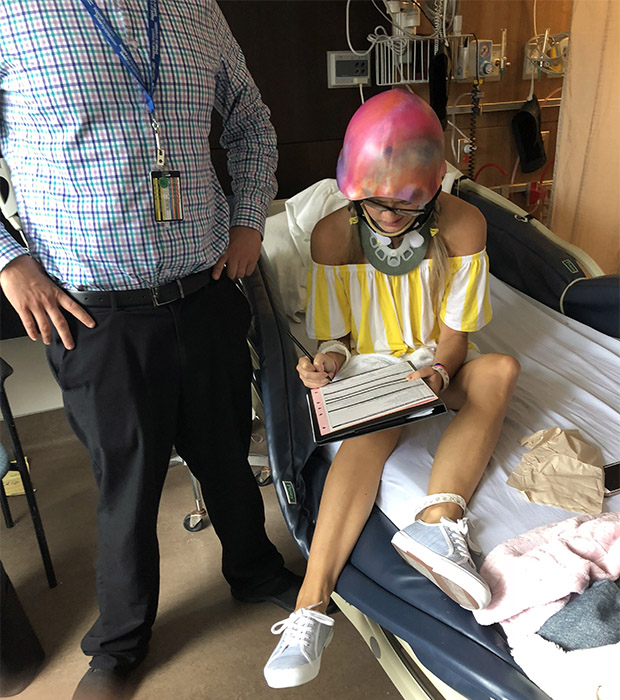

Jean woke in the hospital with no memory of the accident, but thankfully, he was in the hands of a world-leading trauma team who provided lifesaving care when he needed it most. In the hours that followed, he underwent multiple surgeries to stabilize his fractured collarbone, arm, and shoulder and care for his bruised lung and kidney tear. He was fitted with a rigid neck brace to protect the fragile C2 injury as it healed.

Healing, one day at a time

Remarkably, only one week later, Jean was stable enough to return home — a testament to the lifesaving, expert care he received. “Jean had a lot of what we call near misses” says Dr. Mohammed. “If his C2 fracture had shifted even slightly, he could have suffered a massive stroke, or his brain could have swelled, and he could have died. If his kidney laceration had been deeper, he might have bled out. Even his rib fractures could have punctured his lung and caused a life-threatening emergency. He had a lot of angels watching over him that day.”

Jean’s recovery over the next six months was extensive. He followed a strict rehabilitation plan with limited mobility to protect his spine, regular follow-ups, and scans. Each day required patience, persistence, and learning what his body could handle.

“I’m like a bike — titanium is great.”

— Jean Lebel

“Hearing my doctors say that people rarely survive these kinds of injuries made me realize just how lucky I was, and that I owe that to the care I received at The Ottawa Hospital,” says Jean.

Although he still has some lasting effects from the injuries, including reduced grip strength, he is doing remarkably well. “I have a lot more metal in my body than the average person,” he jokes. “I’m like a bike — titanium is great.”

A history of extraordinary care

This wasn’t Jean’s first life altering injury, nor was it his first time receiving care at The Ottawa Hospital. In 2016, he fell from the roof of his cottage in Gaspé, Quebec, shattering his hip. A few months after receiving surgery in Quebec City, his femur went into necrosis. That’s when he turned to The Ottawa Hospital for an urgent, full hip replacement.

He was walking the day after surgery and home the next day. That experience left a deep impression on him. He reflected on how much medicine has advanced — a surgery that once required weeks in hospital, like a hip replacement, now allowed him to go home after a day.

Six years later, he returned to The Ottawa Hospital following his cycling collision, again receiving care from some of the very best physicians in the country.

A commitment to giving back

Despite everything he endured, Jean still cycles today — more carefully, and rarely on the road. “The accident shifted my perspective on life,” he says. “I decided to retire because I want to live life to the fullest. There’s still so much I want to do and experience. I enjoy spending time at my place in Gaspé, and I want to make the most of every day with my family and friends.”

Incredibly, his bike was almost untouched in the crash. “All the impact went into my body,” he reflects. He keeps it as a reminder of how close he came to losing everything.

“If I could give one piece of advice to others, it would be: don’t wait for an accident to give.”

— Jean Lebel

Jean now feels a deep responsibility to support The Ottawa Hospital. “The Ottawa Hospital changed my life twice. I feel it’s my duty to donate for the care I received. If I could give one piece of advice to others, it would be: don’t wait for an accident to give. Just give, because it makes a difference — to you, and to others.”