Published: May 2024

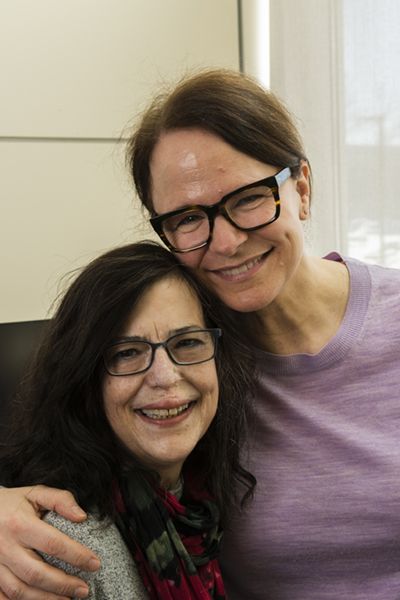

Emmy Cogan was extremely tiny when she arrived in this world, but the impact of her birth was big. Born at 23 weeks gestation, she weighed only 515 grams — that’s just over one pound. Emmy was one of nine babies enrolled in a world-first cell therapy trial to heal the lungs of preemies and was the first in North America to receive the therapy. Now, that promising trial is ready for its next phase.

Her early arrival happened not long after first-time parents Alicia Racine and Mike Cogan returned from a trip to Hawaii. Alicia was back at work as a 911 operator for the Ottawa Police when her water broke.

“My sister works with me, and she brought me to The Ottawa Hospital’s General Campus. I was in a lot of pain, and I wasn’t too sure what was going on. And then we found out that it was contractions, and I started dilating,” explains Alicia.

The baby would hold on for another six days before being born on February 20, 2023. Those few extra days in the womb were critical to give Emmy a chance at life. “It changed the game entirely for us and her. She was able to be intubated, and she just started fighting from that moment on,” explains Mike.

Health challenges lie ahead

Initially, Emmy was cared for in The Ottawa Hospital’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), followed by 10 days at CHEO before returning to our hospital.

Emmy’s first month of life faced many challenges, including a duct between her heart and lungs that wouldn’t close, gastro-intestinal issues causing her to become septic, and concerns of a blood infection. Once Emmy got through those life-threatening issues, she was extubated and put on a high-flow oxygen. “We got to hold her for the first time at that point and my parents were able to be there for that, which was really nice,” says Mike.

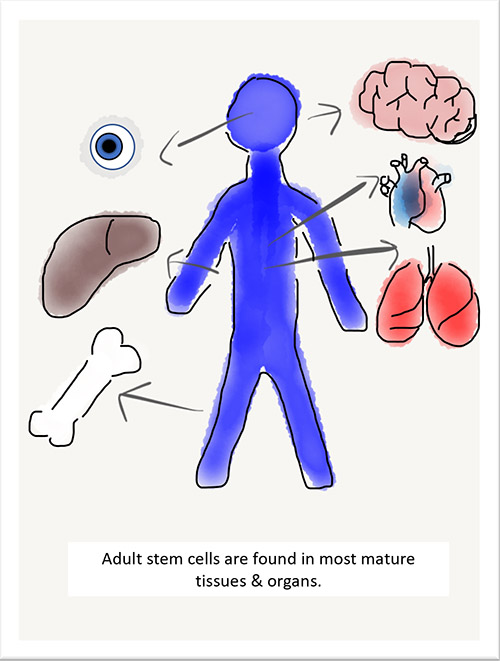

Emmy also developed bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). This is a condition known to affect many preemies. Because these infants are born so prematurely, their tiny lungs are underdeveloped and require extra oxygen to help them breathe properly. But giving this oxygen — critical for survival — can damage their tiny lungs. It’s like starting life with emphysema.

The devastating impact of BPD

In Canada, 1,000 babies are diagnosed with BPD every year. That number jumps to approximately 150,000 worldwide. Often, babies with BPD develop other chronic lung diseases, such as asthma, and may require prolonged oxygen and ventilation.

Additionally, they have a high rate of hospital readmissions in the first two years of life. Babies with BPD often have problems in other organs as well, such as the brain or eyes. There is currently no cure, but this world-first clinical trial led by Dr. Bernard Thébaud, a senior scientist and neonatologist, hopes to change that.

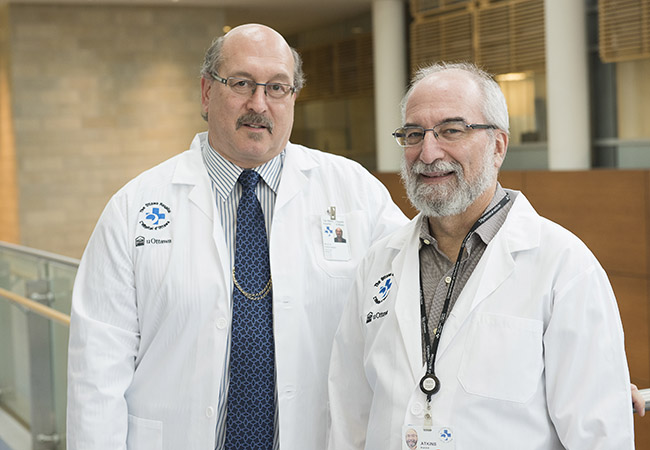

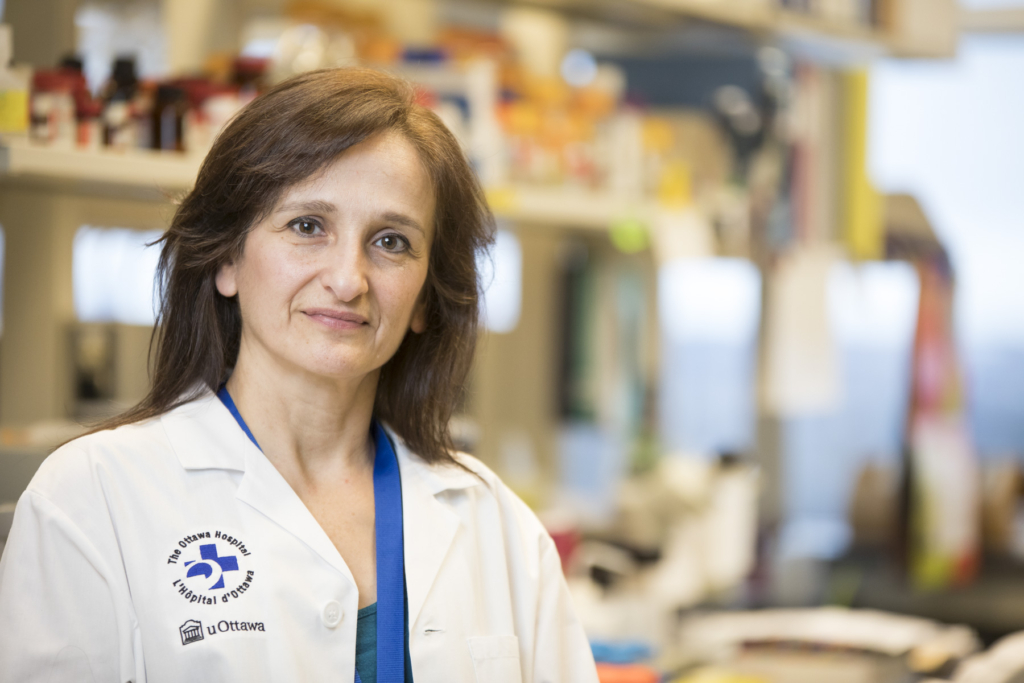

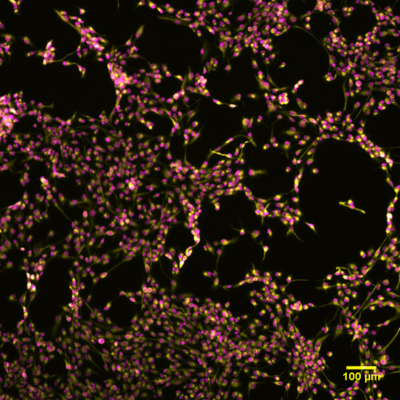

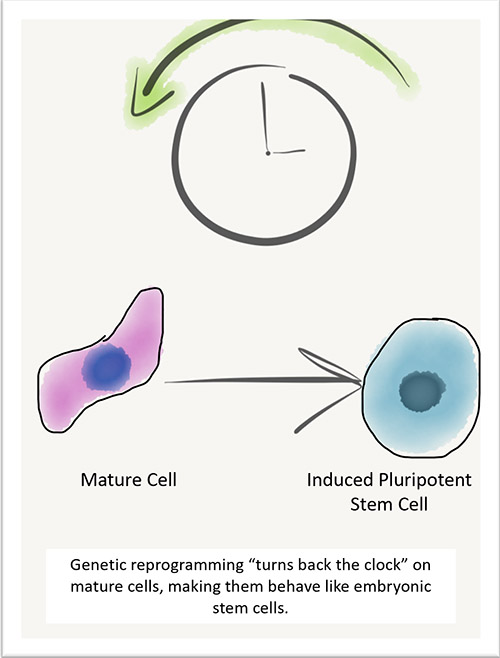

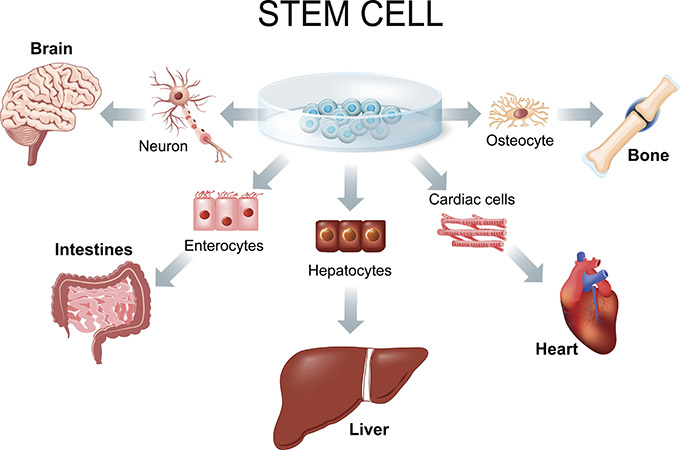

Two decades ago, Dr. Thébaud’s team discovered that stem cells from the umbilical cord — known as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) — could heal lung injury and prevent BPD in newborn rodents. Since then, the team has worked tirelessly, here at home and collaborating with other scientists around the world, to bring this novel therapy to babies and their families through clinical trials. While other trials have tested MSCs for treatment of BPD in premature babies, no other group has used MSCs taken from the whole umbilical cord and processed them the way that Dr. Thébaud’s team has.

What is bronchopulmonary dysplasia?

“In our rodent research, we’ve used stem cells isolated from the umbilical cords of healthy newborns to prevent lung injury or even to some degree regenerate the damaged lung,” says Dr. Thébaud. “We foresee that these stem cells, given during a certain time during the hospital stay of these babies, could prevent the progression of the disease.”

Shortly after Emmy’s birth, her parents met Chantal Horth, a clinical trial coordinator, and were introduced to Dr. Thébaud. “Chantal came to us and said Emmy qualified for the trial,” remembers Mike. “It sounded like a great opportunity.”

"Being a preemie, she’s going to have some health issues, and anything that could help her, we wanted to give her that extra shot."

— Alicia Racine

Saying ‘yes’ to a world-first clinical trial

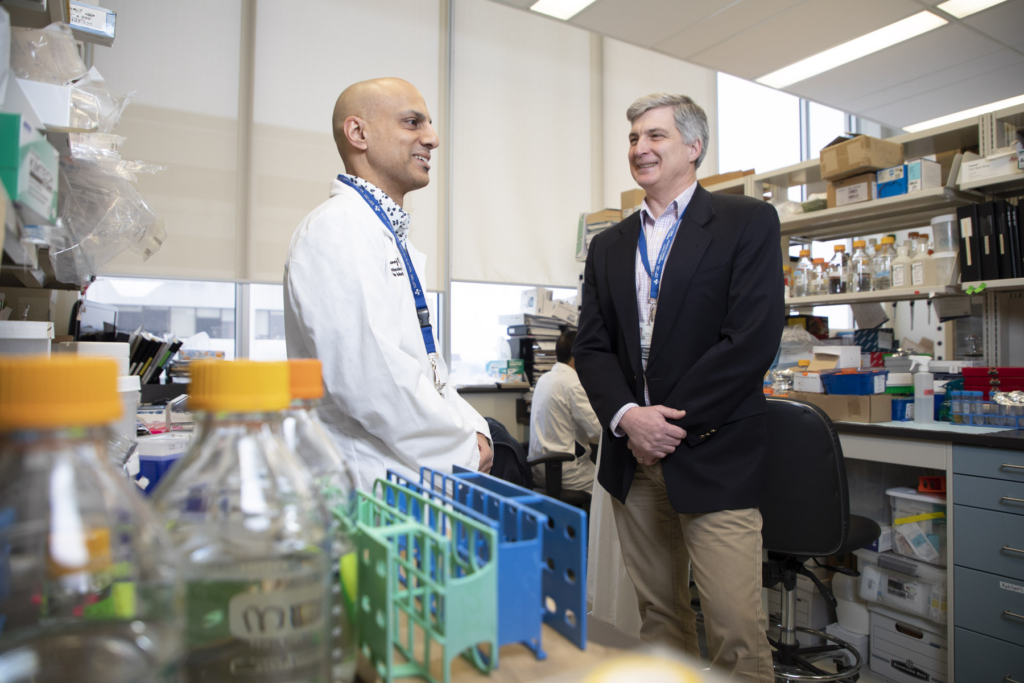

The couple met with Dr. Thébaud, and he answered a long list of questions they had about the trial. “He’s a very personable guy, and it was very easy to talk to him. We trusted him. Being a preemie, she’s going to have some health issues, and anything that could help her, we wanted to give her that extra shot,” says Alicia.

To qualify for the trial, the premature babies — born at 23- or 24-weeks’ gestation at The Ottawa Hospital — had to be seven to 21 days old and treated in the NICU. They also had to require 35% oxygen. This level of oxygen puts them at 60-70% risk of developing BPD. Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre recruited one baby, becoming the second site involved.

On March 3, 2023, at 11 days old, Emmy received an IV infusion of umbilical cord tissue grown from the donated cords of healthy newborns. It was a special moment for everyone involved. She was the first baby in North America to receive this kind of therapy.

"This is the first trial of its kind in the world, and what could be more rewarding than helping preemies?"

– Dr. Bernard Thébaud

“Dr. Thébaud administered the stem cells, and everyone clapped,” says Mike. “She will have follow-up appointments at different stages for two years, and then she’s going to be followed up by phone for 10 years.”

For Dr. Thébaud, it was a moment he and his team had dreamed about. “It was an exciting and huge milestone when that day arrived — after 20 years of work we were able to test this therapy for the first time in a patient. This is the first trial of its kind in the world and what could be more rewarding than helping preemies?”

The next step for this stem cell trial

Thanks to those nine tiny patients, including Emmy, recruitment for the Phase 1 trial is now complete. The purpose of this trial is to test the feasibility and safety of the stem cell therapy. The next phase will test safety as well as how effective it is.

"All the stars lined up to have her be a part of that little piece of history — something that could impact babies like her in the future.”

– Alicia Racine

“Now we can determine if this therapy will make a difference in patients,” explains Dr. Thébaud. “There will be two groups in the next phase — one that will receive cells and one that will receive the placebo — it’s a randomized controlled trial. We’ll need 168 patients to determine if these stem cells make a difference.”

While babies for the first phase were recruited from NICUs at The Ottawa Hospital and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, the next phase will be a multi-centre trial across the country. Dr. Thébaud hopes it will begin by the end of 2024 and it will take two years.

“Working with babies is, I think, the most beautiful job on Earth. Because they’re born, and they have all their life and all their potential in front of them. Our task is to give them a great jumpstart,” says Dr. Thébaud.

As for Emmy, she left the hospital five months after she was born, and while Mike and Alicia don’t know if the stem cells impacted her health, Emmy is doing well. “We don’t know what she would be like without it, but she’s awesome right now,” says Mike. “We felt very fortunate to be in the right place at the right time for our little girl.”

It’s something Alicia feels makes Emmy all the more unique. “All the stars lined up to have her be a part of that little piece of history — something that could impact babies like her in the future,” explains Alicia.

That’s certainly what Dr. Thébaud is hoping for. “It would change the way we care for premature babies. It’s my hope that these tiny patients have a chance to thrive, grow up, and have an impact on the world around them.”

Emmy doesn’t know she’s made history, but that’s ok. For now, she’s keeping her parents busy. She’s pulling herself up and will be walking in no time. She’s also been off oxygen since November 2023, giving her even more mobility. “It was really fun to have her free. We had a cordless baby for the first time! That was a big step when she didn’t need to rely on the oxygen anymore,” smiles Mike.

This Phase 1 trial is funded by the Stem Cell Network with in-kind matching funds from MDTB Cells GmbH. Dr. Thébaud’s research is also possible because of funding from the Ontario Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, The Ottawa Hospital Foundation, and the CHEO Foundation.