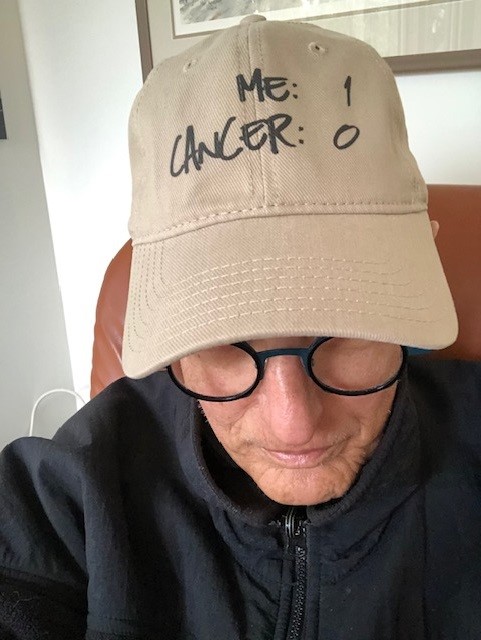

A CANCER JOURNEY

Nurse Sabrina Presta’s very different perspective of life as a patient

Update from Sabrina, February 2026:

“February 4 is World Cancer Day, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to reshare my journey with The Ottawa Hospital Foundation.

After 16 years at the bedside as a registered nurse, The Ottawa Hospital (TOH) will always hold a special place in my heart. The experiences, connections, and lessons I gained there shaped me deeply and continue to guide who I am today.

On January 1st, 2025, I felt a quiet but clear turning point. I followed the guidance of my heart and enrolled in a one-year yoga teacher training. What began as curiosity quickly became a calling. In December 2025, I graduated as a Registered Yoga Teacher.

In May 2025, I made the courageous decision to step away from my bedside role at TOH. This wasn’t an ending—it was a beginning. A chance to care for myself, integrate my experiences with cancer, loss, and burnout, and step into a new way of supporting others.

Today, I teach yoga in my hometown of Embrun and Russell, with a focus on women’s health, prenatal yoga, breathwork, and nervous system regulation. From bedside to mat, the thread of care remains the same.

I’m deeply grateful to TOH for helping shape the nurse, teacher, and human I’ve become. I would love to reconnect with anyone curious about this next chapter—feel free to send me a DM on Facebook.

Hoping our paths cross again… this time, perhaps not at the bedside, but on the mat!

With gratitude, Sabrina”

Published: February 2024

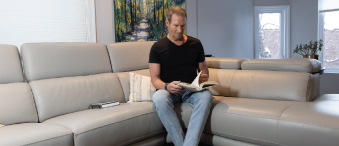

For more than 15 years, Sabrina Presta has been a registered nurse at The Ottawa Hospital. Her home unit is B2, the General Surgery department at the Civic Campus — during the pandemic, B2 became the designated Covid unit for a year. Her team on B2 is close-knit and sticks together not only when it comes to providing compassionate care to patients but also in supporting each other.

In 2020, Sabrina needed that support more than ever. “I was experiencing some mental health challenges, like anxiety. Then, by the end of that year, I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer — that came out of nowhere,” explains Sabrina.

It was the summer of 2020, when Sabrina started getting strep throat regularly — something that she never experienced before. Then she noticed a lump on her neck, and she remembers being afraid of what it might be. She immediately reached out to her doctor.

“The nurse so deeply ingrained in me wanted to read the biopsy report right away. But my intuition guided me wisely, and I decided to wait to meet my doctor face to face.”

— Sabrina Presta

Her doctor ordered an ultrasound, followed by a biopsy. “I had access to MyChart at the time and remember getting a notification that the results were available. The nurse so deeply ingrained in me wanted to read the biopsy report right away. But my intuition guided me wisely, and I decided to wait to meet my doctor face to face. I didn’t want my anxiety to creep up on me and potentially misinterpret the results,” explains Sabrina.

It was December 15, 2020, when she learned the results — the tumours were malignant — it was papillary thyroid cancer. This is the most common type of thyroid cancer and generally impacts people between 30 and 50 years old and appears more often in women. Thankfully, most papillary thyroid cancers respond well to treatment.

“It was during the pandemic, and I was alone when I got the news. I went to my car, and I just started shaking. I was trembling like a leaf. I called a friend, and I was crying on the phone, then I drove home. When I saw my husband, he looked at my eyes and he knew,” says Sabrina.

It was a shock because this active mom of two daughters had no other symptoms, other than the sore throat and lump on her neck. The good news was that it was a non-aggressive, slow-growing form of cancer. It would, however, require a total thyroidectomy — the complete removal of her thyroid gland because there were two cancerous nodules, one in each lobe.

Her daughters were old enough — nine and seven at the time — that Sabrina and her husband sat them down to break the news. “My eldest daughter was surprised to hear the word cancer because I didn’t seem sick. She was sad at first, then was reassured when she heard us talk about the treatment, including surgery. The hardest part for her was watching her little sister’s reaction. She quickly took on the big sister role and comforted her sister,” explains Sabrina. “Meanwhile, my youngest cried ‘Are we still going to have Christmas?’ Her world was just rattled in that moment when she heard cancer. Her great-grandmother died of cancer, and so she thought cancer meant mommy’s going to die.”

She assured her daughters she would be well taken care of, and the surgery would make her better.

In Eastern Ontario, the General Campus of The Ottawa Hospital is home to the region’s Cancer Centre — it is the hub and supports satellite centres from Barry’s Bay to Hawkesbury to Cornwall. The Irving Greenberg Family Cancer Centre, located at the Queensway Carleton Hospital, is also a part of our cancer program. Thanks to state-of-the-art technology and world-leading clinical trials, we can provide a wide-range of care for patients across Eastern Ontario and Nunavut.

As a resident of Limoges, Sabrina was grateful to be able to have her surgery at the Winchester and District Memorial Hospital — a community partner with our hospital — in February 2021. The surgery went well, and the next day, she was sent home to continue her recovery. But days after the surgery, Sabrina developed symptoms that made her nervous, and she went straight to the Emergency Department (ED) at the Civic Campus.

“I was home and had just woken up. I walked to the bathroom and almost fainted — everything went black. I started to have tingling sensations and numbness in my legs, arms, and face,” remembers Sabrina. “After my surgery, I was given discharge instructions from my nurse. Those were two signs to look out for in the post-operative phase, as my body was adjusting to life without a thyroid gland. I woke up my husband, and he drove me to the ED right away.”

“It was an act of kindness that went a long way for me. It taught me that you can really leave a lasting impression on someone’s life experience.”

— Sabrina Presta

Now Sabrina found herself as a patient, in her own hospital, and something “magical” happened. She was waiting to be seen when a respiratory therapist she works with saw her. “He took a few moments out of his busy shift to come over to me. His kindness gave me the opportunity I needed to be comforted and to cry. My tears flowed as I was feeling overwhelmed, tired, and scared of my current reality,” explains Sabrina. “He stayed right there with me. I was very weak, and he helped guide me to the bathroom. Before he left, he gave me tea and crackers. It was an act of kindness that went a long way for me. It taught me that you can really leave a lasting impression on someone’s life experience. He was present. This respiratory therapist gave me that gift.”

As a nurse who diligently practices her profession with compassion, being on the receiving end was eye-opening. “When I was a patient, this word became the hope I needed.”

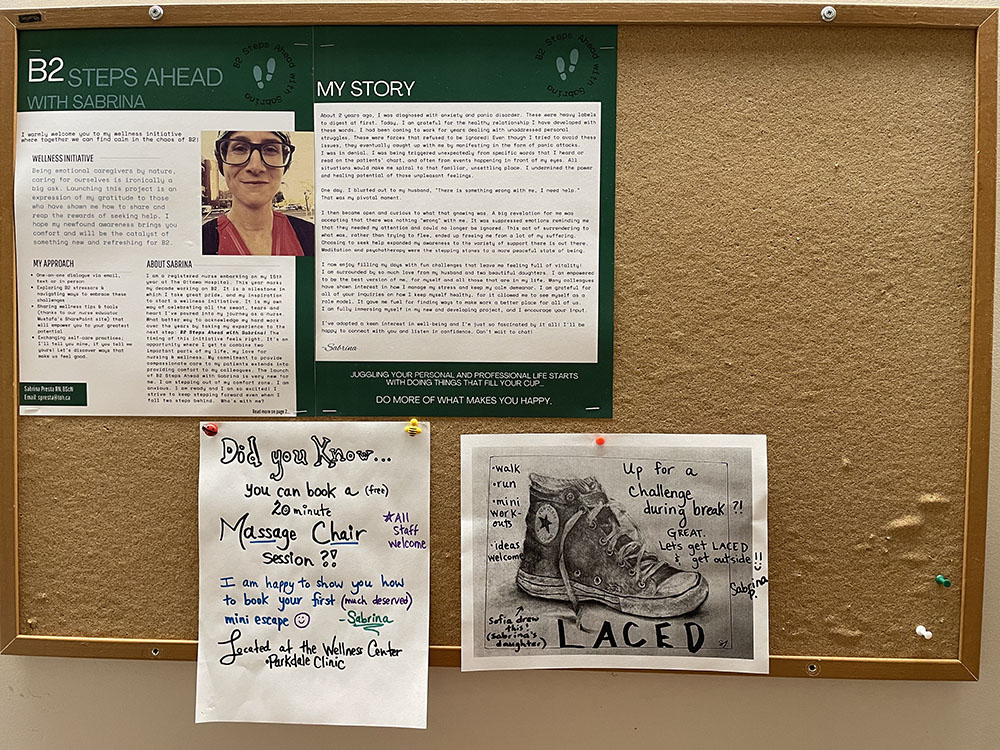

Sabrina soon received good news — what she was experiencing was normal after her type of surgery, and she was able to go home. Within six weeks, she was back at work with a different outlook as a nurse. She was inspired to create her own wellness initiative for her B2 team called B2 Steps Ahead with Sabrina — a collaboration to help colleagues with their mental health. “I created a special room on our unit, the Rest Room, where colleagues can go and recharge in a quiet space during their shift. It even has twinkling lights to relax.”

Her experience with cancer has taught her to slow down and take care of herself holistically. When she is not working on the frontlines, you will probably find her outside either running, walking, practicing yoga, or writing. A dear colleague even gave her the nickname, “Mother Nature.” “I just love being outside! The fresh air gives me something ineffable,” smiles Sabrina.

Today, she can look back on her cancer journey with gratitude. “It is a privilege to work as a registered nurse in facility that gives me a sense of fulfilment.”

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research, and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa.