Published: November 2023

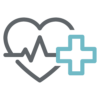

Tanya Di Raddo was 15 years old when she started having severe headaches — she was diagnosed with migraines. As time progressed, the headaches continued. Decades later, she turned to The Ottawa Hospital and was diagnosed with not one, but two illnesses — a brain tumour and multiple sclerosis (MS).

By her late 20s and early 30s Tanya was married and had two children, and the headaches remained a constant part of her life. As her kids grew, she faced a difficult time when her son began suffering from mental health challenges. He was later diagnosed with first-episode psychosis, so she pushed her health issues to the side and persevered.

As time progressed, the headaches worsened — there were times when Tanya couldn’t lift her head off the pillow because the pain was so debilitating. It was still considered a migraine, but she also started to notice something wrong with her right hand. “I don’t know if I’d describe it as tremors, but my right hand would form a claw,” remembers Tanya.

Shocking discovery of a brain tumour plus an MS diagnosis

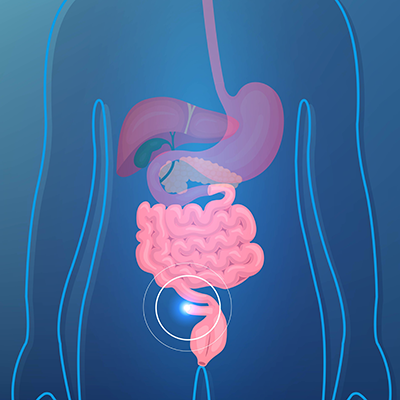

By the spring of 2021, Tanya started to experience pain in her left eye — soon her vision deteriorated significantly. “You know when you see dark clouds in the sky? It was like that in front of my eye. I could kind of see peripherally, but at night, I couldn’t see car lights out of that eye at all, not even colour,” explains Tanya.

“I knew something big was wrong for a long time, so in some ways, the MS diagnosis made sense, but the discovery of a tumour as well was a shock.”

— Tanya Di Raddo

After an extensive examination by her eye doctor, she was referred to the University of Ottawa Eye Institute of The Ottawa Hospital. She met with a neuro-ophthalmologist and was diagnosed with optic neuritis, an inflammation that damages the optic nerve. However, Tanya also needed further testing to better understand the root of her headaches and vision loss. She never imagined what that test would reveal.

Read our Q&A with Dr. Fahad Alkherayf

MRI results showed both MS lesions and a brain tumour. “I knew something big was wrong for a long time, so in some ways, the MS diagnosis made sense, but the discovery of a tumour as well was a shock,” explains Tanya.

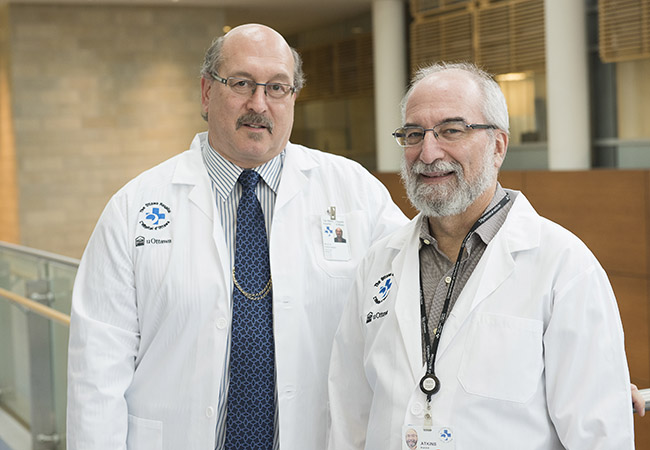

She was immediately referred to Dr. Fahad Alkherayf, a leading skull base neurosurgeon at our hospital. The MRI from mid-summer 2021 showed a large tumour at the back of her brain. “It was a three-and-a-half by five-centimeter mass — the size of a small orange. It was a meningioma, which is a benign tumour that is slow growing, but it was putting pressure on her brainstem and affecting her neurological function,” explains Dr. Alkherayf.

Due to the size of the tumour and the impact it was having on Tanya’s life, Dr. Alkherayf believed surgery was needed within a few months.

In the meantime, she turned to The Ottawa Hospital’s MS Clinic where she met Dr. Mark Freedman, a world leader in MS treatment and research. “She was referred to us after having her vision affected back in mid-2021. We proceeded to confirm a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS and then got her onto effective therapy as soon as possible,” explains Dr. Freedman.

A plan for specialized brain surgery

As her MS treatment got underway, surgery to remove the tumour was scheduled for early November. According to Dr. Alkherayf, the surgery carried significant risk.

“The tumor was pressing at the back of the brain — which we call the cerebellum — as well as on the brainstem.” he says. “The brainstem is the main structure which controls a person’s ability to breathe, walk, and state of consciousness.”

“It’s thanks to having a specialized team who work closely with our neuro-anesthesiologists to operate this equipment that we’re able to provide this technique.”

— Dr. Fahad Alkherayf

Neural monitoring, with what’s known as interoperative neuromonitoring, is an important part of this type of specialized surgery. It allows neurosurgeons to watch the patient’s brain and brainstem functions while attempting to remove the tumour. This is where The Ottawa Hospital excels.

“We’re lucky in that we have good support from the hospital where we can do two or three surgeries at the same time with the ability to monitor the patient,” says Dr. Alkherayf. “It’s thanks to having a specialized team who work closely with our neuro-anesthesiologists to operate this equipment that we’re able to provide this technique.”

The Ottawa Hospital has invested to support this expertise, as it can be challenging to have the right people to operate specialized equipment and interpret the information.

During Tanya’s operation, the surgical team sent a signal through the brain to stimulate her muscles to ensure they were responding during the operation. “Even though she was asleep, we’re still able to look at the function of the brain and brainstem, as if she’s awake,” says Dr. Alkherayf.

Additionally, the system also helps the surgical team monitor the cranial nerve, which controls swallowing, for example. This prevents any possibility of damage during the surgery. If the nerves become irritated during the operation, the surgical team gets a signal.

“When that happens, we stop immediately and change our course of action during the surgery,” says Dr. Alkherayf.

“If you don’t have that technology, then there is the risk of causing damage and you wouldn’t notice it until the patient wakes up.”

— Dr. Fahad Alkherayf

Not just saving a life, but also maintaining quality of life

For Dr. Alkherayf, it’s not only about saving a life, but also about maintaining quality of life. He acknowledges it puts more stress on the team knowing they are caring for a young person, who has many years ahead of them.

“A good analogy is a bomb squad. They want to disable and remove the danger without causing any problems or damage,” he says. “That’s what we’re doing when we remove a tumour like this. We want to remove it without causing any other damage that could impact the patient’s life.”

The good news for Tanya is the whole tumour was removed during the almost eight-hour surgery. This provided her relief from the excruciating headaches she suffered, and her vision has improved, but colour is not crisp yet. “It’s like an older TV. It’s not 20/20, but it’s better than it was,” explains Tanya.

Looking forward

It’s been two years since that complex surgery with no signs of recurrence to date, and she’ll be closely monitored by Dr. Alkherayf for up to 10 years.

Tanya also continues to be in the care of Dr. Freedman for her MS. She has some challenges with her mobility and regularly uses support to get around, and MS flare-ups continue to impact her day-to-day living.

“I’m doing better today, but cognitively it impacts my life,” she says. “It’s the little things we take for granted that I notice, like leaning forward to make a meal or cutting something. The numbness in my fingers makes it difficult, and sometimes my leg will give out.”

The reality of facing two serious illnesses at the same time is not a uniqueness Tanya was aspiring for or ever thought she’d face, but she’s grateful to have access to the best treatment options available, from complex surgery to ongoing, compassionate care.